NAMS task force report on Evidence-based traditional medicine for health care in India

BACKGROUND

The National Academy of Medical Sciences (NAMS), in a meeting on April 2022, decided to constitute a task force on Evidence-based Traditional Medicine (TM) for Health Care in India.

A Task Force (TF) with experts in Biomedicine and Traditional medicine engaged in research and practice was formed under the chairmanship of Prof Bhushan Patwardhan. The following terms of reference were provided to the TF. This document reports the TF’s work during the six-week duration in October and November 2022.

To identify the need for “Evidence-based traditional medicine for health care.”

To identify the deficiencies that need to be addressed,

To make recommendations based on the gaps concerning national needs and current policies in Evidence-based traditional medicine for health care.

INTRODUCTION

India has a distinct pluralistic health system with the modern or allopathic system practiced and legitimized and several traditional medicine systems. Traditional medicine (TM) is the total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness.1 In India, two separate Ministries govern the health system- the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) governs the contemporary modern system. In contrast, the Ministry of AYUSH governs the TM systems, including Ayurveda, Yoga, Siddha, Unani, and Sowa-Rigpa. In this section, we briefly present the milestones in the history of medicine systems in India and the existing gaps where TM may have a relatively effective role in health.

TM use in the Indian health system – attempts at integration

The Bhore Committee (1946) that laid the foundation of the health system for independent India did not pay enough attention to TM systems, resulting in the marginalization of Indian systems of medicine (ISM) and thus monopolizing Western biomedicine. However, several nationalist scholars, including Sir Ram Nath Chopra (1948) and KN Udupa (1958), highlighted the need for evidence-based integration. Several policies by the Government since 2002 have encouraged the revitalization of local health traditions and emphasized the need for integration and strengthening of Traditional Medicine in India. The significant policies comprise the National Policy on Indian Systems of Medicine and Homeopathy 2002, which acknowledged the long neglect of traditional systems of medicine and mentioned the revitalization of folk medicine for the first time. Subsequently, in 2005, the National Rural Health Mission suggested mainstreaming Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH) and revitalizing local health traditions to strengthen primary health care.2 Further, the National Health Policy (NHP) 2017 emphasized prevention through lifestyle advocacy and health care delivery through integration, colocation, and medical pluralism. The policy interventions lead to recognition of the role and potential of AYUSH systems/TMs in achieving national health targets and their mainstreaming and integration into the national health system. The 12th Five Year Plan (2012-2017), followed by NHP 2017, National Education Policy (NEP)-2020, and the latest National Digital Health Mission (2020), have strongly advocated the need for harnessing the potential of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH) systems by its integration in mainstream healthcare.

However, true integrative health care has remained elusive in medical education, health research, health services, and administration. Thus, there is a need to further this vision with more attention to the emerging evidence from TM systems in the larger interest of people.

The term ‘integration’ is perceived differently in different parts of the world based on local culture, practices, and priorities. India must define integration and create its model based on its cultural strengths and ground-level requirements. Mere co-location, bridge courses, or cross-pathy practice may need more views of integration. For effective integration, India must transform from a pathy-based reductionist approach to person-centered holistic health care.3 The scientific basis and vision for rational integration of the traditional medicine system are made explicit by some of the landmark publications.4

Gaps in medical systems and health care in India from a medicine systems perspective

Although allopathy (modern medicine) remains dominant globally, the role of traditional, complementary, and integrative (TCI) medicine can no longer be ignored. The World Health Organization (WHO) formally recognizes the role of TCI as a vital component of integrated health services to meet Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Shanghai Declaration 2016 considers traditional medicine’s growing importance and value, which could contribute to improved health outcomes, including those in the SDGs. The WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023 sets out the course for TCI to foster its appropriate integration, regulation, and supervision as a vibrant and expanding part of health care. It aims to harness the potential contribution of TCI to health, wellness, and people-centered health care and promote its safe and effective use through the regulation of products, practices, and practitioners. This report uses the term TM, representing Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative (TM/TCI) medicine in line with the WHO’s recommendations and emerging global consensus.

According to the Global Centre for Traditional Medicine, World Health Organization, about 40% of existing pharmaceutical drugs have originated from traditional medicine.5 The rising use of conventional and complementary medicine by people stems from patient dissatisfaction with modern medicine, the success of complementary medicine in chronic conditions, which have not responded well to modern medicine treatment, and patients’ desire for holistic care. The world is becoming more eager to find other satisfying modes of treatment and care than Western healthcare models. The global indicators in medicine evolved through the ages and have demonstrated a gross shift from medical care towards health care, covering preventive, promotive, and rehabilitative aspects besides therapeutic management and cure. This has drawn attention to integrating different health systems to complement and supplement unmet needs.

Though beneficial in acute diseases and injuries, modern medicine is less effective for treating chronic diseases or enhancing health. In the majority of the cases with autoimmune disorders, skin conditions, and lifestyle disorders, modern medicine has very few substantive offers, and even the expensive drugs and surgical procedures that are promoted for these conditions are not effective in actually correcting them. The four primary determinants of health are nutrition, lifestyle, environment, and genetic composition. If any of these components is compromised, it may lead to ill health and require medical care. Health systems’ current focus is pharmacological interventions based on laboratory diagnostics, symptomatic cures, and prescription drugs. In the currently dominant modern medicine’s drug and surgery approach to health, the role of diet, lifestyle, and exercise, the prime factors of daily living are neglected or ignored. The therapeutic value of foods, herbs, and natural treatment methods from massage to meditation are often forgotten. The organic basis of health and well-being is obscured by the very complexity of diagnostic and treatment measures. Necessary attention to clinical acumen, physiological interventions, nutrition, diet, lifestyle, and behavioral interventions based on body-mind synergy is missing.

There is a possibility to fill these gaps by putting the best of modern and TM systems together for comprehensive holistic treatment cum care. The WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases 2013-2020 is recommended for recognizing, promoting, and integrating traditional knowledge and cultural heritage and integrating Traditional Medicine in the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs).

Apart from NCDs, the role of TM systems in combating certain infectious diseases has been studied and offers encouraging results, especially in conditions where biomedicine has limitations, such as Systemic Lupus Erythematous, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Interstitial Lung Disease, to mention a few. Also, the potential of complementing TM to improve beneficial effects, reduce side effects of biomedicine, or improve adherence is being increasingly realized. This is often through studies and practices by individual practitioners or institutions; however, a clear recommendation for formal adoption into routine practice is rare. For example, filariasis is a neglected tropical disease prevalent in many parts of India, and patients undertaking usual allopathy treatment as prescribed in the national program often are left with complex sequelae that biomedicine has no cure for. A successful example of integrating filariasis treatment with traditional medicine is offered by the work at the Institute of Integrative Dermatology, Kasargod,6-8 but it remains an institutional specialty and expertise. During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the use of TM to prevent or control early-stage COVID-19 has been widespread, and documented by multiple studies. Ayush drugs such as AYUSH 64,9 Kabasura Kudineer,10 and Anu Tail11 were found to be effective and safer adjuvants to standard care in COVID-19 treatment (details in following section). A first-of-its-kind integrative protocol for managing COVID-19, including biomedicine and TM, was released by the MoHFW. Such potential must be explored to benefit the people and health system.

TM IN INDIAN HEALTH CARE SYSTEM – STATUS AND POTENTIAL

TM in the health system in India

Significant efforts and investments have ensured the preservation and development of TM in India, making it widely available in private and public hospitals. 2018, there are 4035 government hospitals and 27951 dispensaries to provide medical care facilities under AYUSH. As of March 2020, the AYUSH component was included in 31 State Programme Implementation Plans; AYUSH facilities were available at 497 District Hospitals, 2757 Community Health Centres, and 7779 Primary Health Centres across the country. Nearly twelve thousand AYUSH practitioners were in contractual positions under the Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram and other programs.

TM at the family level in India

A nationally representative survey documenting the usage of various medical systems in India reported home to be the main source of Indian TMs.12 However, in the current context of the health system in India, the family or household level is not considered adequately – the infrastructure includes the clinics and hospitals but not the household and community, and the drugs and supplies considered are only from the pharmaceutical preparations but not those from plants and other local resources used by people.13 In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the relevance of the family or household tier has been more apparent and is proposed as the fourth tier of the health system.13 The concept of the fourth tier is people’s self-reliance in health, wherein people’s capacity for self-care and their responsibility to the health system and its values are respected. Traditional knowledge of health practices is gaining increasing attention in behavioral medicine as lifestyle diseases are rising.

TM use for specific health conditions

Patients often use multiple systems of medicine simultaneously, especially in cases where biomedicine has limitations. For example, over one-third of cancer patients presenting to oncologists in a hospital in Kerala reported using TM.14 The popularity of TM use in pediatric oncology cases has received due consideration from the International Society of Paediatric Oncology.15

Ayush in COVID-19

The extensive use of Ayurveda and Yoga by the people in India during the COVID-19 pandemic is a recent example. The Ministry of Ayush developed and launched the Ayush Sanjivani mobile application to generate data on the acceptance and usage of Ayush advocacies among the population and its impact on the prevention of COVID-19. The findings of a cross-sectional analysis of the collected data highlighted that a good proportion of the representative population has utilized Ayush measures across different regions of the country during the COVID-19 pandemic and have considerable benefits in terms of general well-being and reduced incidence of COVID-19. The National Repository on Ayush COVID-19, available on the AYUSH research portal of the Ministry of AYUSH, provides details of over 125 COVID-19-related Ayush studies, including pre-clinical, epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and scientific publications (https://ayushportal.nic.in/Covid.aspx). The Ministry of AYUSH’s Inter-disciplinary Ayush R&D Task Force, consisting of scientists, pulmonologists, epidemiologists, and pharmacologists from premier organizations and research institutions, formulated guidelines for Ayush clinical and observational studies in COVID-19 covering various aspects of trial protocols.16 This is an important example worth emulating.17

Policy context for TM in India

National Health Policy 2017 (NHP2017) has reiterated the mainstreaming of AYUSH through co-location with modern medical practice, offering it to “persons who choose” to use these systems of medicine. The policy recommends that yoga be widely used in schools and workplaces for health promotion. Continuing from previous policies, the NHP 2017 repeats the need to standardize and validate Ayurvedic medicines and establish a robust and effective quality control mechanism for AYUSH drugs. It mentioned the need to develop infrastructural facilities for teaching institutions and capacity building for education and research. Similar to the recommendations of earlier committees, the NHP2017 advocated convergence at the Community Health Worker level, with Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) and the Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees as the point for initiating convergence and mainstreaming of AYUSH into the public health system. The utilization of traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) practitioners at the Health and Wellness centers under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (Ayushman Bharat) program represents one more step towards inclusion of T&CM practitioners in the national health system, albeit with little apparent parity with the status or remuneration being provided to doctors of modern medicine.

Regulatory environment for TM in India

Appropriate legislation has been developed to regulate traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) in India, which includes the Indian Medicines Central Council Act of 1970, the Homeopathy Central Council Act of 1973, and the Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940 (amended in 2009). The Indian systems of medicine, i.e., Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Sowa-Rigpa, were regulated by the Indian Medicine Central Council Act of 1970 earlier. Very recently, the National Commission for Indian System of Medicine (NCISM) Act, 2020 repealed the Indian Medicine Central Council Act, 1970 for regulating the medical education system and practice of Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Sowa-Rigpa and their adoption of the latest medical research.

Legislation has been put in place to protect the intellectual property rights of knowledge holders. T&CM practice is licensed at certificate, graduate, and postgraduate levels and includes completing compulsory rotating internships. A separate essential drug list for Ayurveda and Unani medicines has been developed. Herbal medicines used in Ayurvedic, Unani, and Siddha treatment are included under Schedule E of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules. They are available on prescription from licensed pharmacies or licensed practitioners in case of non-prescription medications. Good manufacturing practices (GMP) regulations guide the manufacturing of herbal drugs. Manufacturing units are granted licenses requiring 3-yearly renewal. GMP manufacturing has to be based on existing pharmacopeias and monographs and involves routine inspection of facilities and testing of final products at designated government laboratories for analysis.

Financial resources for TM systems

The TM systems allocation comprises that of the Ministry of AYUSH. After the separate ministry was formed, the allocation was considerably increased to Rs 3050 Crore in 2023. However, this remains a meager sum compared to Rs 89,155 Crore for the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. The scope of the Department of Health Research needs to be extended to include transdisciplinary health-related research to create better synergy and resource optimization.

Status of TM research in India

Research on TM in India is on the rise, more steeply in the recent decade, as indicated by the Scopus database, which shows a peak in the number of publications in the TM field, especially Ayurveda and Yoga. Notably, nearly half of the published works on Ayurveda are from pharmacology and medicine, drawing attention to the need to focus on the strengths of TM systems in prevention, promotion, and wellness rather than only treatment. India has several institutes conducting Yoga-related research, such as Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana (SVYASA)- Bangalore, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Somaiya University (Mumbai), Visva-Bharati, and Santiniketan.18 The increase in studies on yoga in India is steered by dedicated funding for yoga research, mainly from the Ministry of AYUSH and contributions from the Quality Council of India (QCI). The Indian Government has been keen on promoting the integration of Yoga intervention into the current healthcare system.

The recent establishment of integrative medicine departments at critical national institutions such as AIIMS and NIMHANS is expected to steer research and evidence-based integration of TM in practice. Research in the recent two decades into the fundamentals of some TM systems has provided new insights into understanding the relevance of these systems in current times of stagnation with some of the approaches in modern medicine. For instance, the initiative of Ayurvedic biology has led to several studies into restoring physiological functions for treatment and improved well-being.19 Pioneering works under the Ayurveda biology program, such as the work on the concepts of Prakruti and its association with the gut and oral microbiome, have provided the impetus for the translation of Prakruti principles for personalized approaches to health.20 Ayurgenomics has emerged as a promising research area offering newer insights into the genotypic-phenotypic classification and genetic basis of the Ayurveda concept of Prakriti.21,22 Ayurgenomics research involving whole-system clinical trials23 and whole exome sequencing has indicated the potential to bring innovation by integrating a unique phenotyping approach for the identification of predictive markers and their translation for predictive, personalized medicine.24,25

The potential of TM contributions to the Indian health system

Most of the Indian population lives an unhealthy lifestyle and is exposed to the risk factors associated with NCDs. Middle-income countries with limited health professionals tend to have a higher prevalence of NCDs, which are not diagnosed at pre- or early disease stages, which places a heavy burden on health systems. The National Health Mission emphasized involving AYUSH personnel to address the shortage of human resources in the available healthcare system.26 The shortage of healthcare professionals can be solved by providing more human resources and promoting preventive healthcare and a healthy lifestyle that can reduce disease prevalence, hence the need for trained medical personnel.27 By promoting healthy lifestyles and reducing risk factors common to several diseases, TM systems can reduce the burden on healthcare systems.28

Globally, nearly 41 million people succumb to the burden of NCDs, amounting to 74% of deaths.29 The prevalence of NCDs in India is on the rise30 while the burden from infectious and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) persists. Mental health issues are a growing concern and pose distinct challenges, primarily because of the minimal success of modern medicine in this area.

The critical strategy for reducing the rising burden of NCDs is adequate prevention and better management. The critical components of management include screening, detection, and treatment. Besides individual behavior and lifestyle modifications, several other factors like economic, social, and political approaches also act as critical factors of NCDs.31-33 For most NCDs, the available biomedical treatment is limited and expensive, contributing to the increased economic burden.34 Hence, the prevention of NCDs is emphasized.35

As a traditional form of exercise, yoga benefits the human body by encouraging physiological and psychological well-being and preventing the development of NCDs. Yoga practice is recommended by the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity.36 Yoga is a mind-body practice that includes physical and mental exercise promoting physical and psychological well-being.37,38 Yoga is a cost-effective and feasible exercise for individuals of all age groups. It can reduce the risk factors for developing NCDs, such as obesity, impaired glucose metabolism, psychological imbalance, high cholesterol level, and blood pressure.

The practice of yoga alters the mind’s capacity to facilitate systemic function across multiple organ systems, thus affecting the different systematic axes of the body, including hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA-axis), the cardiac axis,39 psycho-neuro-immune axis, ghrelin axis40 and normalization of biomarkers of neuro- immune axis not only at the molecular level but at the genetic level also.41

The above evidence supports the promotion of Yoga for a healthy lifestyle and NCD prevention. The relevance of Yoga as a powerful preventive intervention in NCDs through neural, endocrine, immunological, cellular, epigenetic, and genetic mechanisms is increasingly recognized and understood by modern science approaches.42 A National Programme for Control of Cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and Stroke was undertaken during 2016-17, followed by 3044 participants for six months. The intervention studies included basic lifestyle modifications, yoga practice, and simple Ayurvedic drugs. The results of this vast program are encouraging and demonstrate the role of TM systems in controlling NCDs.43 It is prudent for India to invest more in these measures to tackle the rising burden of NCDs.

Studies at several departments at AIIMS, Delhi, including cardiology, anaesthesiology, pulmonary medicine, neurology, and genetics, have strongly highlighted the need for integrative medicine as the future path of the Indian health system. Works at other institutes of repute, such as the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, have shown the potential of utilizing the TM concepts of lifestyle modifications in understanding and treating metabolic and liver diseases.44,45 The Yoga-CaRe trial that tested the effectiveness of Yoga-based cardiac rehabilitation programs in India and the UK has provided evidence for Yoga-based options to conventional care.46 A landscape review of Yoga research studies in 2020 highlights the rising works of yoga research in various conditions and the restoration of physiological functions for health.47 Similarly, NIMHANS has provided evidence on the effectiveness of Yoga in the prevention and treatment of mental illnesses and for mental well-being and, importantly, the lessons for adopting an Integrative Health Care model.48

TM interventions that have the potential to improve overall health and prevent the incidence of NCDs, including mental health problems, deserve serious consideration by the Indian health system.49-56 Identifying TM interventions that are to be relatively better than conventional care or improve outcomes when combined with conventional care and exploring the best utilization of these in routine health care should be done on priority.

CHALLENGES TO IMPROVE TM USE IN INDIAN HEALTH SYSTEM

India has a pluralistic healthcare system. There is a co-existence of conventional medicine with traditional medical systems, which are regulated under the umbrella framework of Ayush. However, there needs to be more interaction between the two medical systems, with practitioners of each system working independently in practice and clinical decision-making.

Unlike Western countries, traditional medical practitioners are licensed to practice in India and can offer the full range of interventions to the general public.

Conventional medicine and Ayush practitioners are educated separately within the health system. This state of affairs nurtures avoidance patterns in which an integrative approach is not encouraged because of conceptual conflict rooted in distrust between the two systems.57

In contrast, Integrative Medicine movement emerged in Western countries, intending to integrate evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine into mainstream medical practice.58 However, Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners themselves have limited legal sanctions to practice.

The TM systems in India are very distinct and complex. The practitioners of these systems work in silos without engaging in cross-talk and exploring possibilities of integration. As a result, the TM system is fragmented, and its full potential must be harnessed to address public healthcare needs. The worldwide integrative medicine movement is focused on integrating evidence-based CAM practices into the mainstream rather than integrating whole CAM systems with conventional medicine.

We face the challenge of integrating multiple legitimized whole traditional medical systems with conventional medicine in India. Generating “scientific evidence” for the medical system is much more complex than for selected practices. Limited integration of TM with mainstream healthcare delivery systems creates significant gaps in the optimal utilization of its strengths. Students of conventional medicine do not get adequate knowledge about TM systems as it is missing in the curriculum.59 On the other hand, students of TM systems have significant exposure to conventional medicine during their training. The disproportionate inclusion of conventional medical topics in the TM curriculum hinders the development of students’ core competence in respective TM systems.

This leads to the unhealthy trend of cross-system practice, resulting in TM physicians practicing conventional medicine. There is an emerging trend amongst conventional medicine practitioners to prescribe herbal supplements and other over the counter instead of (OTC) TM products without sufficient training and knowledge of these systems.60

Adequate evidence from well-conducted studies is not yet available regarding TM interventions to develop integrative treatment protocols to facilitate making informed choices for optimal health care. Inadequate data on herb-drug interactions poses a significant challenge when it is administered as an add-on therapy.61 This also creates challenges for ethical clearance to evaluate the safety and efficacy of add-on TM treatments in clinical integrating TM treatments with a standard of care at the point of care, especially since TM treatments are often complex and multimodal. It isn’t easy to generate a complete phytochemical profile of the multi-herbal formulations and understand the complex synergism of the constituents. Studying complex TM treatments using conventional pre-clinical and clinical study design is also difficult. Reductionist methods are commonly used for the evaluation of TM treatments and formulations. As a result, evidence backing the real-world practices of TM systems is scarce, even as piecemeal evidence is being built on fragmented elements of TM treatments and formulations. There is a need to balance evidence-based medicine and evidence-informed healthcare.62

The materia medica/pharmacopeia and food inventory of TM systems like Ayurveda need updating to include articles widely used today. Understanding the properties of new foods and drugs from the TM epistemological framework is lacking. This limits the development of TM-based health advisories that consider prevalent dietary practices and the usage of botanicals.TM treatments are personalized, and there is heterogeneity in the protocols being followed by various practitioners, even within one TM system. Research to report outcomes of real-world practice in TM systems is non-existent. This makes recommending specific treatment protocols for public health interventions in priority areas difficult. In the prevailing situation, integration is patient-driven, and the use of TM in the healthcare system is not optimal as it is not knowledge-driven. As a result, while the pluralistic healthcare system in India gives freedom for both practitioners to practice and people to choose different treatment modalities, it is impossible to make informed decisions regarding the appropriate use of conventional medicine and Ayush systems.

Challenges in implementation studies for TM use in the Indian health system

Below is a list of the long-standing challenges in implementing TM for disease prevention and cure.63

Academic limitations

Research and development in the field: Research in the field of Traditional medicine has remained neglected until recently. Small sample numbers, inconsistent or varied outcomes, and poor research methods are key factors that make studies regarded as defective and insufficient. Other issues include weak controls, inconsistent treatment descriptions or product descriptions, low statistical power (perhaps due to small sample sizes), and a lack of comparisons with other therapies, a placebo, or both.64 Folk traditions and wisdom of traditional medicine are handed over from generation to generation in India. They are termed ‘people’s health culture with the scarcity of documentation and patents in traditional medicine. Attaining patients with modified and improved TM components require the promotion of investments in research, which is currently inadequate.

Technology to preserve the research data: While there is an increasing trend with the use of TM worldwide, the research in this field is still inadequate, with serious difficulties in data acquisition and preservation. The research data generated is not safeguarded and preserved so that it can be retrieved and reproduced. This poses challenges to retrieving, sharing, and future use.

Protocols and standard operating procedures (SOPs): Despite the rising research and acceptance of the field of TM, specific studies are reporting adverse health effects of TM; this may be due to the variable quality, efficacy, and contents of herbal products as a class of medicinal products. In this regard, developing SOPs for research studies based on TM, which has been less attended to thus far, is a limitation to evidence generation.65

Funding: There is a limited higher education support system in traditional medicine, such as PhD and postdocs. Limited opportunities for higher education focused on TM limit young scholars from taking up TM topics, thus limiting the evidence generation and career progression with works focused on TM.

Publication avenues: For the wide acceptance of research, publication in high-impact journals is paramount, but a limited number of high-impact journals consider publishing research data on TM not only due to limitations in the research data but also due to the lack of approval for TM research.

Administrative Limitations

Administrative bodies: There are fewer administrative policies specially made for traditional medicines. In Medical institutions, obtaining ethical approvals for conducting TM research is often challenging as the committee members are not experts in TM and do not feel equipped to make decisions on TM projects.

Development and enforcement of policy and regulations: In TM, there is a wide range of products, techniques, and practitioners. Some provide health benefits, while others come with risks or are solely motivated by business interests. Given its limited resources, the government should choose where to concentrate its efforts to give consumers the most significant and safest type of healthcare while meeting the requirement to protect consumer choice, and it must be supervised within its jurisdiction and in TM systems, referred to as codified medical systems, policymaking and standardization are arguably the most challenging issues. For instance, some courses might emphasize the physical parts of the healing system more than others, which might place more emphasis on the mental and spiritual aspects. For this to be done correctly, it would be necessary to have policies and particular nodal agencies to control and offer guidance. The WHO recommends that TM be implemented in any country’s healthcare system, and the formulation and implementation of national policies and laws as per the country’s situation are needed.66,67

Awareness among the medical practitioners about TM: Providers in the conventional healthcare system are less informed of TM and the research upcoming in the field. This creates barriers to innovative works in TM to generate more evidence.

Quality: Implementation and functioning of Inter-University centers are required to generate enthusiasm and data out of collaborative research between various Institutions through student exchange and Inter-University projects.

Collaboration: The anticipated unification of the nation’s Traditional Health and Modern Medical systems suffers poor implementation and clearly defined procedures.

Integration between Western medicine and Traditional Medicine: A significant barrier to the incorporation of TM into mainstream medical practices is the absence of pharmacological and clinical data on the bulk TM items.68

Integration of TM into National and Primary Healthcare: The traditional medicine research is focused on ‘testing interventions’ rather than taking the learning forward and building a ‘program’ based on respective interventions. Hence, the research output does not advance into practice or policies. Amongst the TM systems in India, Ayurveda has been studied most (∼8000 papers in PubMed); however, this has hardly resulted in the generation of practice guidelines or even public health programs, and the same may be the case for other TM systems.

The research on traditional medicine intervention must be followed further in health policy and systems research. implementing an intervention is more than management and is now considered a science. It focuses on applying research in a real-world setting.69 Implementation research is the “scientific study of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions into clinical and community settings to improve patient outcomes and benefit population health.”

Implementing studies on traditional medicine is urgently needed to assess its value for improving public health systems.70 This needs consideration of the following steps:

Prioritizing the evidence-based interventions for implementation in community settings

Study of acceptance and utilization of TM interventions by the community or public health systems

Assessment of effectiveness by studying Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS) in diverse settings

Development of health systems based on the learning from the implementation studies

Transforming the data for evidence-based policy decisions and utilizing the learning from primary research

Appropriate clinical protocols for TM system

Research on Traditional Medicine should consider its foundations and epistemology. Most of the studies focus on interventions, ignoring the concepts of TM.71 This approach leads to a fragmented view of TM and may get a false negative or partial understanding of the scenario. Most TM therapies are focused on health, so they are customized and include a ‘package’ rather than a ‘product.’ The following challenges need to be addressed for the development of clinical protocols that explore TM concepts or interventions:

TM practices of the real world are reduced to convenience-driven methods

Lack of cross-talk between researchers making TM ‘monodisciplinary’

Over-emphasis of TM terminologies and practice approaches restrict widespread applications of important concepts

Ignorance about multi-disciplinary research restricts understanding of TM

Replicating protocols used in modern medicine limits the value of TM

Insufficient validated measures for disease diagnosis and outcome assessment

The holistic nature of therapeutics is converted into a reductionist approach suitable to conventional research

Ontological differences posing knowledge gaps between modern and traditional medicines

No systematic efforts for bridging the communication gaps

Short-term goals and utilitarian approach of researchers that ignore TM foundations

A superficial review of research proposals making the less imaginative and non-productive research process

Comparative efficacy studies for TM treatments

Traditional Medicine-based practices or interventions can be used for many reasons. Expected benefits of TM may include health promotion, disease prevention, treatment as standard therapy, adjuvant care with mainstream medicine, prevention of complications, improving the primary intervention’s safety, rehabilitation, palliation, and many other goals in managing health and diseases. The value of TM needs systematic assessment and sound evidence for its intended benefits.72 However, the research methods should be based on the expected benefits. The research should be much more than a randomized controlled study and focus on real-world usage of TM.

Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER) follows evidence generation and synthesis for assessing the benefits and harms of two or more methods for prevention, management, or monitoring a clinical situation and improving care delivery in a real-world scenario. The CER helps all the stakeholders make informed decisions to improve health care.73

Generally, randomized controlled trials with tight protocols improve the study’s internal validity and are considered the best for regulatory requirements. The stringent protocols may limit the applications of findings in real-world settings, reducing the external validity or ability to generalize the findings. In such situations, pragmatic studies, observational studies, synthesis of available literature, and careful analysis of prevalent practices may help address the limitations of RCTs or such explanatory trials. The most important factor differentiating TM from modern medicine is the history of safe use. Hence, TM may follow the Reverse Pharmacology (RP) approach, where knowledge about respective TM therapy can be borrowed from clinical practice and further can be tested in systematic studies, including explanatory trials or mechanistic studies.74 RP utilizes an epistemology-sensitive approach and involves a collage of study methods for various levels of biological organization. It embraces study designs from omics to health system research for evidence generation for safety and efficacy.

The role of clinical practitioners is central to this process.75

In the context of TM research, CER’s principles and important considerations can be useful.

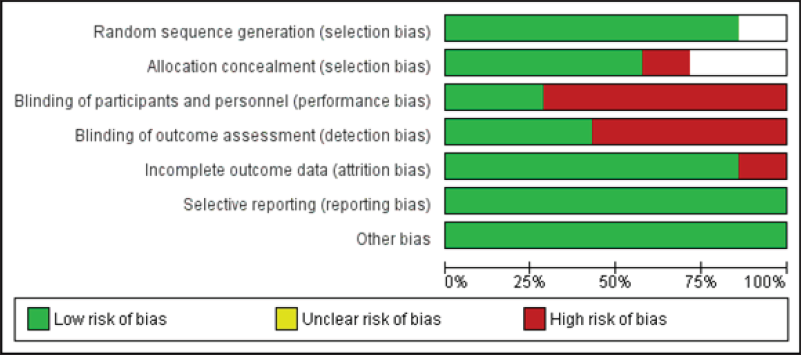

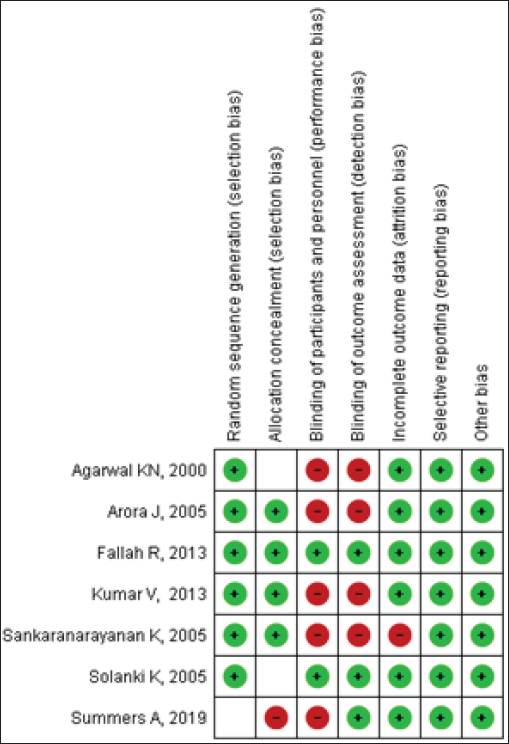

Review and synthesis of current medical literature with risks of bias and methodological lacunae

Identification of needs of clinical practice and related gaps in current literature

Generate new scientific data following methods suitable to research questions

Transcending disciplinary boundaries for health goals

The National Health Policy 2017 aims to mainstream Ayush and make it available at all levels for,adequate Universal Health Coverage. The policy also recommends mainstreaming with effective collaboration and cooperation with different health systems. The cross-talk will strengthen validation, evidence, and research efforts and generate a common pool of knowledge. To achieve this goal, several opportunities should be created to facilitate the cross-talk between TM practitioners and those from modern medicine. Registration of new clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests increasing collaborations between modern medicine institutions and the Ayush sector.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OPTIMAL TM USE IN INDIAN HEALTH SYSTEM

Bridging the evidence to action gap for TM

The specific measures to improve the utilization of evidence from TM into practice are as follows:

Build health information systems that are integrated nationally for specific diseases

Plan evidence synthesis (meta-analysis, systematic and narrative reviews) and make the data available to clinicians and policymakers

Develop modules for creating public awareness about health interventions and preventive measures

Identify research priorities based on research gaps that would be helpful for funding agencies for the allocation of research support

Undertake efficiency-oriented clinical trials and foster clinical translation

Subsequently, plan the implementation of interventions that have proven efficiency

Provide implementation grants to support the practice and health delivery models in individual states

Develop and implement objective TM indicators to identify TM-specific inputs to assess the level of progression, facilitators, and barriers to a predefined objective of the outcome of health delivery.

Policies for optimal TM integration in India

The goals of policies aimed to achieve TM integration should be:

Set up a mechanism in national regulatory bodies to bridge the gap between conventional medicine and TM

Introduce the evidence on TM research in modern medicine curricula

Improved inclusion of TM interventions for health finance mechanisms in India, including government schemes and private medical insurance.

Inclusion of TM interventions in health delivery mechanisms and targeted programs at national and sub-national levels for specified health conditions, its prevention, and to promote well-being, aimed at maximizing the health delivery to all of the population. This should be guided by the ethos of the UN’s promise to “leave no one behind,” which is the soul of its central, transformative promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Inclusion of evidence-based, safe, and effective TM interventions that have proven efficiency in clinical/ financial/or patient-reported wellness outcomes in specific clinical conditions in NCDs and NTDs.

Skilling and utilization of TM human resources to deliver TM services in specific clinical areas by their proactive inclusion in health system building blocks at appropriate levels.

Research for improved TM use in the Indian health system

Research into methods for optimal TM integration: More research focused on the various models globally to inform strategies for the integration of TM in mainstream health care is recommended. Higher education institutes engaged in medicine, social science, and policy research should be promoted to undertake such research on priority.

Development of epistemology-sensitive protocols: Increased investments into researching TM systems and keeping to the principles and philosophies of these systems are essential.

Limitations of contemporary research training and approaches for TM research being recognized, promoting research into developing epistemology-sensitive approaches and protocols for TM research is recommended.

Comparative efficacy studies for TM interventions: Integration of TM evidence into health care and national programs needs to be informed by comparative effectiveness studies. Promoting comparative effectiveness research is hence recommended.

Promoting the exchange of TM knowledge

It is recommended to include specific and level-appropriate skill development programs for the Ayush health workforce. These can be mandatory and program-specific.

The following programs could be undertaken to improve transdisciplinary research:

Education and Research:

Inclusion of introduction to TM/TCI in syllabi of modern medicine.

The recent initiative of the National Medical Commission to include Yoga in the MBBS curriculum is an important step in this direction.

Emphasis on the role of TM/TCI systems, especially in managing NCDs, lifestyle, behavior modification, and nutrition.

Students internships in cross-disciplinary institutions should be encouraged

Transdisciplinary research project grants for faculty and PG students to support and collaboration research on TM/TCI

Providing opportunities for teachers from TM and modern medicine colleges for mutual exposure through faculty exchange programs Include TM/TCI-based “best practices for healthy living” within the school syllabus and curricula, spread across classes 1 to 9, for children in an appropriate manner.

Clinical Practice:

CME programs on TM/TCI, especially for Family Medicine/General Practitioners and allopathic clinicians

Development of specialized credit courses for TM/TCI interventions

Training medical practitioners on selected interventions (e.g., Ksharsutra, Massage, Meditation, Yoga therapies)

Offer TM/TCI courses to modern medical graduates, which shall provide them with the opportunity to practice the systems under a regulated environment in select foreign countries

Public Health:

Mainstreaming evidence-based Ayush systems by including them in national programs

Identification of local health practices and studies on their acceptance and effects

Studies on TM-based culturally conducive care for local health priorities

Awareness of health practices concerning locally available resources

Make accessible Ayurveda and yoga-based self-health care tools that are language and context-specific within the broad well-being agenda.

Strategic collaborations with the World Health Organization’s Global Centre for Traditional Medicine (WHO GCTM) and other national/global organizations should be explored to bring effective integration in people’s best interests.

THE WAY FORWARD

More evidence needs to be generated for appropriate TM use; it is important to utilize existing evidence from TM systems in health policy and practice in India. While recognizing that the current scenario of more scope for evidence generation is a result of underinvestment in research in TM for several past decades and more research needs to be promoted, it would be appropriate to also focus on promoting the uptake of the existing evidence. Developing clinical practice guidelines integrating the existing evidence derived from TM systems is an essential measure of this.

The integrative protocol for COVID-19 released by the Ministry of Health offers a distinct example. More such protocols for real-world applications are required.

The way forward to appropriate utilization of TM evidence for the Indian health system lies in systematic scrutiny and broader application of the existing evidence while promoting more and improved research in TM systems.

In the recent few years, India has witnessed significant developments in the direction of promoting TM system contributions to health care. Notable among these is the formation of the Integrative Health System Committee by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog. The Committee provided a white paper to the Indian government on the integrative health system. The Lancet Citizens Commission to Reimagine India’s Health System is sensitive to the need to address AYUSH-related challenges for a better health system in India. Establishing the WHO GCTM in Jamnagar, India, is an essential milestone in promoting TM/TCI use for a healthier world. These initiatives are good examples of concrete actions for evidence from the TM system for population health in India.

This TF has attempted to scrutinize evidence on Ayurveda interventions for iron deficiency anemia. The subgroup comprising TM and modern medicine practitioners worked collectively on this task to scrutinize evidence on managing iron deficiency anemia and answer if that can address the failures with current management and improve outcomes. The details in the supplementary material suggest the potential for better anemia management using Ayurveda interventions regarding clinical outcomes, adherence, and costs. (Annexure 1 and 2).

Hence, this TF thinks that the way forward to appropriately utilize evidence from TM/TCI for health care in India can be made through small concerted efforts to demonstrate the use of TM/TCI evidence for national health needs in the current health system.

In this regard, we suggest the following for immediate tangible outcomes:

Identify up to four priority areas to undertake this activity. The criteria for this choice could be

areas that are persistent challenges to national health where biomedical approaches have had limited success

where national programs based on biomedicine have resulted in limited public health impact

where interventions from TM are available and are relatively simpler and backed by the experience of clinical use by TM practitioners.

Exemplar guidelines for the management of selected clinical conditions based on evidence from TM

The TF suggests potential areas of iron deficiency anemia, filariasis management, infant growth and development, and mental health and well-being.

Develop the methodology to demonstrate and evaluate the implementation of TM/TCI interventions in the above-identified areas. The following steps are recommended:

Expert group formation: Identify a pool of expert TM/TCI practitioners to lead this initiative in coordination with the designated task force subgroup. It would be best to handpick experts based on clinical experience in the selected conditions.

Draft implementation plan: Develop an implementation plan and note for the initiative for review and suggestions from TF members and invited experts.

Workshops for technical finalization: Finalize the implementation plan in two-day long workshops for each selected topic. The experts at the workshop would systematically scrutinize the available evidence and clinical experience and arrive at a choice of interventions for chosen conditions and the related technical details.

Implementation: Each identified interventions could be implemented systematically through chosen centers such as government hospitals and health centers. Implementation spread out through twenty outlets in five states of India could generate an adequate variation for learning. It would be best to design these implementation studies and identify a nodal agency to execute these systematically through protocol development, approvals, process documentation, data collection and analysis, monitoring and evaluation, and reporting. An 18-24-month duration with biannual reviews and mid-course corrections is suggested. The Ministry of Ayush and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, may allocate the required financial resources for this work.

Advocate the uptake of the lessons from the above implementation exercise into the health system at different levels, including policy, practice, and research.

Revisit the procedures and the strategies for the above activities and provide recommendations for future activities.

For longer-term impact and addressing the root cause of limited and appropriate TM/TCI evidence, we recommend Commissioning an expert group in research methods to develop the appropriate methodology for evidence generation sensitive to TM/TCI epistemology and demonstrate the application of its select conditions of national priority.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments

The task force members thank Prof Dr. Shiv Kumar Sarin (President, NAMS), Prof Umesh Kapil (Secretary, NAMS), and Dr. Ajay Sood (Deputy Secretary, NAMS) for support to the task force activities. We thank Dr. Bhanu Duggal and colleagues, especially Dr. Mohit Nirwan and Dr. Vasuki Rayapati (AIIMS Rishikesh) and Mr. Akash Saggam (SPPU, Pune), for documentation on evidence related to Ayurveda in the management of IDA and Dr. Monika, Mr. Kanupriya, Ms. Pooja, Ms. Swati and Mr. Saurabh (PGIMER, Chandigarh) for research assistance. We also thank Dr. Madhuri Kanitkar and colleagues, especially Dr. Sourav Sen and Dr. Shweta Telang-Chaudhari Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, Nashik, Prof. Seema Patrikar, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Dr. Manohar Gundeti, Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences, Mumbai and Dr. Gaurang Baxi, DY Patil University Pune for contributing to synthesis evidence on oil massage for infant health.ANNEXURE 1: AYURVEDA FOR IRON-DEFICIENT ANAEMIA – IS ENOUGH EVIDENCE AVAILABLE?

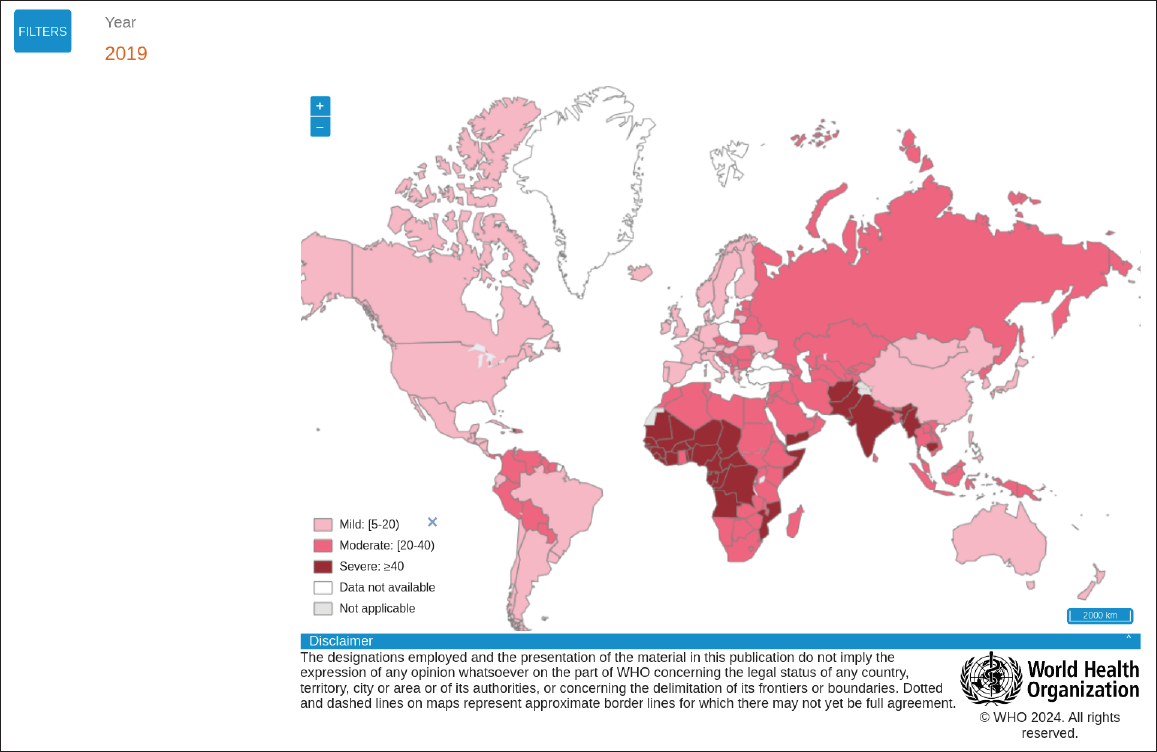

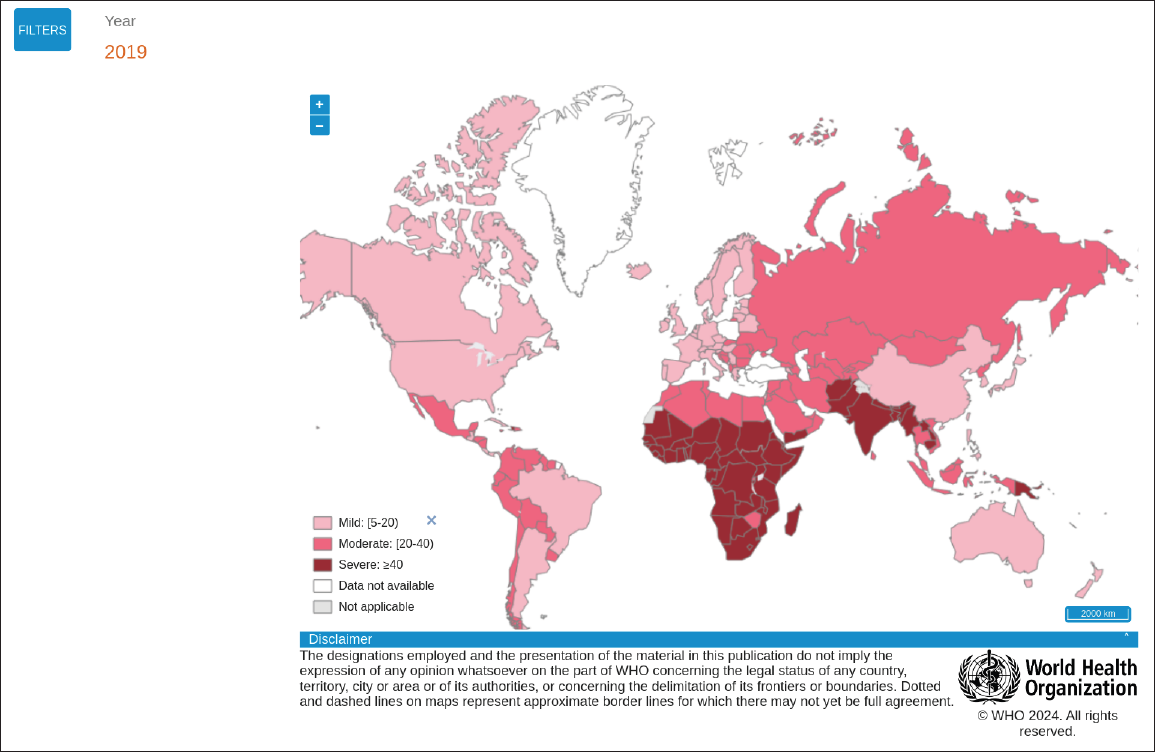

Introduction

Iron-deficient anemia (IDA) is India’s most prevalent micronutrient deficiency, affecting 1.5 billion people globally. IDA is a multi-factorial disorder. Pregnant women [Figure 1], children [Figure 2], and the senior population suffer from IDA often. By the WHO recommended Hb levels for diagnosing anaemia [Table 1] half of pregnant women and children under 5 years age in India are anaemic [Table 2].| Age groups | No Anaemia | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children 6-59 months of age | ≥11 | 10–10.9 | 7–9.9 | <7 |

| Children 5-11 years of age | ≥11.5 | 11–11.4 | 8–10.9 | <8 |

| Children 12-14 years of age | ≥12 | 11–11.9 | 8–10.9 | <8 |

| Non-pregnant women (15 years of age and above) | ≥12 | 11–11.9 | 8–10.9 | <8 |

| Pregnant women | ≥11 | 10–10.9 | 7–9.9 | <7 |

| Men | ≥13 | 11–12.9 | 8–10.9 | <8 |

| Indicators | Urban (%) | Rural (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Children aged 6-59 months who are anemic (<11.0 g/dl) | 64.2 | 68.3 |

| Non-pregnant women aged 15-49 years who are anaemic (<12.0 g/dl) | 54.1 | 58.7 |

| Pregnant women aged 15-49 years who are anaemic (<12.0 g/dl) | 45.7 | 54.3 |

| All women aged 15-49 years who are anaemic | 53.8 | 58.5 |

| All women aged 15-19 years who are anaemic | 56.5 | 60.2 |

| Men aged 15-49 years who are anemic (<13.0 g/dl) | 20.4 | 27.4 |

| Men aged 15-19 years who are anemic (<13.0 g/dl) | 25.0 | 33.9 |

Ayurveda for IDA management

Ayurveda is an ancient Indian traditional medicine system. In Ayurvedic terminology, anemia is known as pandu, which means paleness. Pandurogmentioned in Ayurvedic classics is similar to IDA. Ayurveda gives importance to the patient’s physical appearance and symptoms and has been used to treat thousands of patients for centuries. Modern Ayurveda doctors consider blood reports and the traditional practice of nadi examination, physical appearances, and symptoms. We searched the literature for ayurvedic preparations and comparative studies in Pubmed and Google Scholar and prepared Table 3.| Study | Study design (n) | Inclusion criteria | Ayurvedic preparation | Results | Authors’ conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUNARNAVA MANDURA | |||||

| Ambika, 20131 | Pre-Post (50) | Children aged 10 to 14 | Punarnavadi Mandura 500 mg BD and Dadimadi Ghritha 10 ml B.D with lukewarm water for 84 days (3 lunar months) | Statistically significant response in hemoglobin and other hematological investigation | Punarnava Mandura is effective in management of Pandu roga (IDA) |

| Khan Delwal et al., 20152 | Pre-Post (24) | Pregnant women belonging to the age group of 18 to 40 years with 6 g% to 10 g% of hemoglobin | Group A (n = 15): 2 tablets of Punarnava Mandura (500 mg each) thrice a day; with one cup of buttermilk; Group B (n = 9) 2 tablets of Dhatri Lauha (500 mg each) thrice a day with one cup of lukewarm water (administered for 90 days) | Statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference was noted in Hb%, MCV, MCH, and MCHC. It shows that Group A is better than Group B | Punarnava Mandura is comparatively better in Garbhini Pandu |

| Pandya & Dave, 20143 | Pre-post single group (50) | Patients having Hb% below the normal range (in men: 7–13 g/dl and in female: 7–12 g/dl; age group 50 and 80 years | Patients were given 2 tablets (250 mg each) of Punarnava Mandura twice a day after lunch and dinner with the Anupana of 100 ml of Takra (freshly prepared butter milk) for the duration of 90 days. | Statistically insignificant differences were found in hematological parameters, that is, Hb%, Total blood cell (RBC), MCV, MCH, MCHC, PCV, ESR, platelet count and in serum, iron Study Follow up was for 1 month | Punarnava Mandura is a unique poly herbo mineral formulation which may work as a Panduhara and Rasayana in the patients of geriatric anemia and can counteract most of the pathological manifestation s related to Pandu Roga in old age (geriatric Anaemia). |

| (No study reported any of the adverse events.) MCV: Mean corpuscular volume; MCH: Mean Corpuscular Haemoglobin; MCHC: Mean Corpuscular Haemoglobin Concentration; PCV: Packed Cell Volume; ESR: Electrocyte Sedimentation Rate. | |||||

| DHATRILAUHA | |||||

| Srikanth, 20104 | Open-label multi-centric trial (458) | Age between 15 to 60 years; Hb Levels 6 to 10 gm/dl. | Dhatri Lauha 500 mg BD for forty-five days with warm water. | Significant effect (p < 0.05) in improving the Hb; serum iron, and stored iron (serum ferritin) were increased | The DhatriLauha is safe and significantly increases the Hb, serum Iron and Ferritin in subjects with Iron Deficiency Anemia. |

| Daya Shankar, 20145 | Randomized, Non blinded and Placebo controlled (30) | 18-70 years age; Hb concentration <12 gm/dl in men or <11 gm/dl in women were included. | Dhatri Lauha and Novayaslauha in dose of 250 mg, respectively BD for 30 consecutive days | After 30 days of treatment, Dhatri Lauha showed significant (p < 0.05) response | The two Ayurvedic preparations are effective, well tolerated and clinically safe for correction of iron deficiency anaemia. The results need to be ascertained at larger scale in multi-centre Study. |

| Rupa para et al., 2013*6 | Parallel random (26) | (No full-text access) | PandughniVati 2 tablets of 250 mg tds and Group B (n10) Dhatri LauhaVati 1 Tablet of 250 mg tds. | Group A The result observed in dyspnoea (60%) and palpitation (53.33%) were highly significant (<0.001). Daurbalya (33.33%), fatigue (40%), anorexia (28.57%) and Pindikodvestana (55.55%) delete, decreased significantlly (<0.05) whereas in pallor (24%), it was not significant. | Better percentage improvement in- Group B consistently in most of subjective and objective parameters. Proving Dhatri Lauha better to Pandughni Vati. |

| (No study reported any of the adverse events. Follow up: NI. * Full text was not accessible.) | |||||

| NAVAYASA LAUHA | |||||

| Study | Study design (n) | Inclusion criteria | Ayurvedic preparation | Results | Authors’ conclusion |

| Daya Shankar, 20145 | randomized, non-blinded and placebo controlled (30) | 18-70 years age; hb concentration <12 gm/dl in men or <11 gm/dl in women were included. | Dhatrilauha and Navayaslauha in dose of 250 mg respectively BD for 30 consecutive days | After 30 days of treatment Navayasa Lauha showed significant (p < 0.05) response | The two Ayurvedic preparations are effective, well tolerated and clinically safe for correction of iron deficiency anemia. The results need to be ascertained at a larger scale in multi-centre study. |

| Mahavir Kho, 20137 | Parallel group clinical study (60) | 18-35 years age pregnant women; hbconcentration 8-10 gm/dl | Group A – DhatriLauha (250) mg T.I.D. in the form of vati, after food for 90 days with ghee/honey. Group B – NavayasaLauha (250) mg – T.I.D. in the form of vati food for 90 days with honey/water | Dhatri&navayas aLauha provided significant result on Hb gm%, RBC, MCV, PC V serum iron percent transferrin saturation and TIBC | DhatriLauha showed significant result in anemia in pregnancy (Garbhin i Pandu) |

| (No study reported any of the adverse events. Follow up: NI) TIBC: Total iron binding capacity; MCV: Mean corpuscular volume; PCV: Packed Cell Volume; RBC: Red Blood Cells. | |||||

| SAPTAMRIT LAUHA | |||||

| Study | Study design | Inclusion criteria | Ayurvedic Preparation | Results | Authors’ conclusion |

| Hiremath & Kulkarni, 20218 | Open-label prospective trial (43) | Age between 12 to 16 years; Hb level 8 to 11 gm/dl. | Albendazole 400 mg before initiating the trial medication. Saptamritalohavati (500 mg) after food with water twice daily for a period of 60 days. Children in the control group received Dhatrilohavati (500 mg) in a similar way | Saptamritalauha is effective in improving the clinical features and hematological parameters significantly and the results were comparable with the standard control. The mean improvement in hemoglobin(Hb) was 1.17 g% in the trial group during the course of treatment (P < 0.001) | Saptamritalauha is effective in the management of Panduroga in children. |

| (No study reported any of the adverse events. The study had 1-month follow-up.) BD: Bis in die (twice a day); IDA: Iron deficiency anaemia; RBC: Red Blood Cells; TID: Ter in die (Thrice a day). | |||||

Current scenario

Oral iron supplementation is a cheap, safe, and effective means of increasing hemoglobin levels and restoring iron stores to prevent and correct iron deficiency. Many preparations are available, varying widely in dosage, formulation (quick or prolonged release), and chemical state (ferrous or ferric form). or the treatment of iron deficiency anemia, current guidelines recommend a dose of 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron of ferrous sulfate per day for a minimum duration of 3 months in adolescents and adults, including pregnant women. However, gastrointestinal side effects in nearly 22% of patients are associated with ferrous sulfate oral supplementation.9 Prominent adverse effects are nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and discomfort with diarrhea or constipation. The bioavailability of these meds is about 20%. Ferrous ascorbate has high bioavailability, from 30–40% up to 67%, but concerns about its safety and cost exist.10 Many studies using ayurvedic preparations to address mild to moderate anemia bear promise. Side effects reported are minimal, and the efficacy of these drugs is equivalent to or even better than the ferrous preparations used to treat anemia, probably attributed to improved compliance. Modern medicine prescribes forms of iron like ferrous sulfate and fumarate, but they have side effects. Prominent adverse effects are nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and discomfort with diarrhea or constipation. Furthermore, they are not cost-effective. Many studies using ayurvedic preparations to address mild to moderate anemia bear promise.Discussion

Punarnava mandura is composed of Triphala, Trikatu, Chitraka, Vidanga, and Pippalimula. Unlike modern medicine’s side effects, the components of Punarnava Mandura are appetizer and carminative.3 Dadimadighrita and Punarnava Mandura are prescribed in pandurog management. Mandura, which is chemically Fe2O3, increases serum ferritin, while punarnava decreases gastric irritation produced by Mandura. PunarnavadiMandura is preferably taken with buttermilk, which has a low pH and contains lactic acid. Iron absorption is aided by reduced pH. Furthermore, iron may combine with lactic acid to form ferrous lactate before absorption, which modern allopathic medicine uses to manage IDA. Dhatrilauhavati contains Lauha Bhasma, an iron supplement that leads to proper metabolism, and Dhatuposhana. Ayurveda experts and allied scientists have worked extensively on various possible formulations and the efficacy of Ayurvedic drugs mentioned in the classical texts. However, the trials suffer from bias and poor reporting. There is a lack of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics studies that can determine the mechanism of action of ayurvedic drugs. The clinical trial methodology is also rarely followed. Up to now, only one multi-centric clinical trial has been conducted with an enrolment of 458 patients. The study was conducted in 11 peripheral research institutes of the Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha and Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, to evaluate the safety and efficacy of dhatrilauha in IDA management. The trial has shown promising results.4 It was observed that the prevalence of anemia was significantly higher in females than males due to the higher iron requirement in the reproductive age group and pregnancy. Out of 400 patients with anemia who completed the study, the maximum number of patients (57.2%) were illiterate and matriculated. It may be due to a lack of awareness of a nutritious diet in less educated and lower socio-economic groups. It may be due to inadequate availability and capacity of the resources for eating a nutritious diet. Few cases reported adverse reactions like burning sensation and nausea. Overall clinical improvement was significantly seen in 77.25% of patients, and a feeling of well-being was observed in 79.75% at the end of the study. The therapy provided a significant effect (p < 0.05) in improving the hemoglobin percentage.Pharmacoeconomics of Ayurveda and Allopathy Drugs

As detailed in Tables 4 and 5, Ayurveda drugs are less expensive than Allopathy medicines. The price (INR) difference is 0.9 rs, 1.07 rs, and 4.7 rs, respectively.11| Sl. No | Ayurveda Medicine | Dosage Form and Strength | Per day Cost (INR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Punarnva Mandoor | 500 mg (Twice a day) | 2.8 |

| 2 | Navayasa Lauha | 500 mg BD (Twice a day) | 2.8 |

| 3 | Saptamrit Lauha | 500 mg BD (Twice a day) | 1.9 |

| Sl. No | Allopathic Medicine | Dosage Form and Strength | Per day Cost (INR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Film-coated | Each film-coated tablet contains Ferrous Ascorbate eq. To elemental iron 100 mg, adenosylcobalamin 15mcg, zinc sulfate monohydrate eq. to elemental zinc 22.5 mg, and folic acid 1.5 mg. (Once a day) | 3.79 |

| 3 | Film-coated | Each film-coated tablet contains Folic Acid IP 5mg, Methylcobalamin IP 1500mcg Pyridoxine Hydrochloride IP 20mg. 10 Tablet). (Once a day) | 3.87 |

| 3 | Ferrous Sulphate manufactured by Facmed Pharma | 28 Tablet. (Once a day). | 6.6 |

Guidelines & recommendations

Although Ayurvedic drugs are well tolerated and are promising in managing IDA without side effects, subsequent phase III/IV clinical trials should be conducted to prove efficacy and long-term safety. The Ministry of AYUSH has advised the use of Trikatu Churna/Guduchi Churna/ Dhanyaka Churna/Shunthi Churna/Jeerak Churna, Dhatrilauha/Punarnavadi Mandura/Dadimadi Ghrita/Annabhedi Chenduram/Saptamritlauha/Mandoor Vataka/Navayaslauha/Drakshavleh/Dadimavleha/Dhātrīavaleha for the management of mild to moderate anemia under the supervision of Ayurvedic Medical Officer.12 The National Institute of Ayurveda suggests the use of Punarnava Mandura for anemic children 125–250 mg BD and adolescent girl/pregnant women 250–500 mg BD; drakshadiavaleha for anemic children 3–5 g BD and adolescent girl/pregnant women 5–10 gm.ANNEXURE 2: OIL MASSAGE FOR INFANT HEALTH

Research Question- Is there enough evidence to recommend oil massage in full-term infants in home settings?Introduction

Newborn, infant, and child health is a high-priority area for sustainable development. Mortality indicators are improving globally. Neonatal mortality is declining, with the world’s neonatal mortality rate (NMR) falling from 37 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 18 per 1000 live births in 2018.1 In India, NMR is still higher compared to many parts of the world. Skin interventions have been implemented to reduce neonatal mortality, demonstrating the role of skin-care practices in neonatal innate immunity.2 Massaging the newborn and infant is a widespread traditional practice in India and most of Asia. Literature suggests the need to study and adapt culturally acceptable interventions, including community-based ones. Infant care practices tend to be region- and culture-specific and influence child health outcomes. Cultural practices are sometimes beneficial and sometimes harmful, and for some, there exists no clear evidence of benefit or harm. Evidence-based prevailing childcare practices and their effects are important to inform practice and public programs. The World Health Organization’s guidelines on ‘Maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience’ 3 recommend gentle whole-body massage for term, healthy newborns for its possible benefits to growth and development. Massage, as much as it has therapeutic value, is also a common cultural routine newborn care practice across many countries. The massage techniques, the steps involved, tactile-kinesthetic stimulation, massage with or without topical lubricant, variety of oils used, etc., may have ethnocultural and eco-geographical variations. But, essentially, massage in newborn infant care is universally prevalent. Massage in infants, with and without oils, has been researched, and several benefits have been reported. These include improved anthropometric parameters such as weight gain velocity and length.4 A meta-analysis of infant oil massage found it effective at promoting physical growth and had a limited risk of adverse skin reactions.5 Most reports on topical applications’ effects on infant skin, termed ‘emollient therapy,’ are from hospitalized babies born premature and requiring intensive care.6 Infant massage therapy studies have predominantly focused on preterm infants with low birth weight with the primary objective of weight gain and the underlying mechanisms for massage leading to weight gain. Clinical studies have proven that the topical application of oil is effective in- enhancing the skin barrier function, reducing infections, and saving the lives of newborns Darmstadt et al., 2004; Darmstadt et al., 2005;7,8

- promoting somatic growth because the fatty acids in the oil provide nutrition supplementation Fernandez et al.,9 Soriano et al., 200010 and

- reducing TEWL (transepidermal water loss), which leads to improved thermoregulation with a reduced incidence of hypothermia Darmstadt et al., 2005; Kulkarni et al.8,11

The tradition of oil massage in India:

Infant massage with emollients is a common practice culturally followed across India. In a survey conducted in the Indian states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh involving 1497 infants, it was observed that infant massage was a highly prevalent practice, with 93.8% of the mothers massaging the baby at least once a day [95%CI: 92.4,94.9].4 It was further observed that 97% of the respondents (mothers, family/caregivers) used Oil as the preferred substance to massage the baby. In a survey conducted among women in Nepal about traditional practices, it was observed that 89.5% of women gave oil massage.13 The massage with oil resembles the Abhyanga procedure prescribed in Ayurveda classics. In the Indian sub-continent, infant massage is generally practiced with topical oil application.Benefits of oil massage:

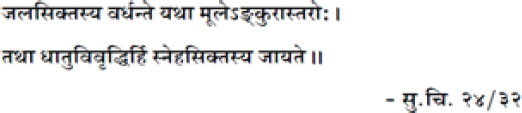

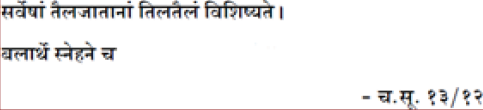

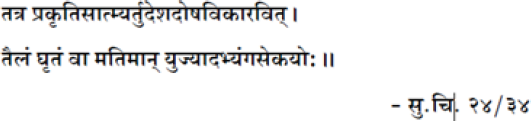

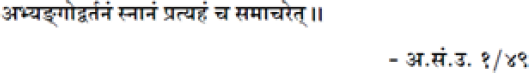

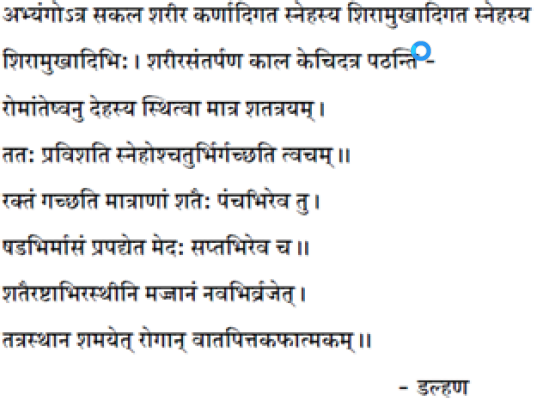

Ayurveda classics have suggested that regular oil massage immensely helps promote the growth and development of body tissues, which is analogous to how regularly watering a plant promotes its growth.

Research studies have shown that the oil applied during infant massage enhances the skin barrier function and thermoregulation, reduces trans-epidermal water loss and neonatal infections and improves skin integrity, neurodevelopment, and mother-infant bond.10 Research on the health benefits of emollient therapy in healthy, full-term infants is scarce.

With this background, a systematic review was undertaken to answer if oil massage for full-term infants can be recommended as a routine practice for infant health.

A systematic literature review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines to determine the current state of knowledge about infant massage.

A literature review for relevant studies was performed on the PUBMED database, and the studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected. Recent research on infant oil massage included studies published from 2000 to 2022.

PICO for the review was as follows:

Ayurveda classics have suggested that regular oil massage immensely helps promote the growth and development of body tissues, which is analogous to how regularly watering a plant promotes its growth.

Research studies have shown that the oil applied during infant massage enhances the skin barrier function and thermoregulation, reduces trans-epidermal water loss and neonatal infections and improves skin integrity, neurodevelopment, and mother-infant bond.10 Research on the health benefits of emollient therapy in healthy, full-term infants is scarce.

With this background, a systematic review was undertaken to answer if oil massage for full-term infants can be recommended as a routine practice for infant health.

A systematic literature review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines to determine the current state of knowledge about infant massage.

A literature review for relevant studies was performed on the PUBMED database, and the studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected. Recent research on infant oil massage included studies published from 2000 to 2022.

PICO for the review was as follows:

- Population: healthy, full-term infants from 0–12 months; preterm infants when intervention was an oil massage

- Intervention: Infant massage (with and without Oil) administered by parents or professionals

- Control group: blank or care as usual or other intervention

- Outcome: weight gain, length gain, No adverse effect

- Study type: randomized controlled trial (RCT), clinical controlled trial(CCT)

| Selected Study and year | Level of evidence | Study design | Population | No. of subjects | Age of infants when intervention administered | Intervention | Frequency | Control | Duration of intervention (days) | Major Outcomes in Massage Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal 200014 i | High | RCT | Full term Birth weight : more than 3 kg | 125 | Started at 6 weeks of age, till next weeks of age | Herbal oil massage Sesame oil massage Mustard oil massage mineral oil massage | 10 min Once a day Similar Swedish massage | Blank | 28 | Oil massage improves weight gain, length gain, mid arm mid leg circumference , blood velocity and blood flow. Sesame oil appears to be better than other groups. |

| Summers et al. 201915 | High | Cluster RCT | Full Term, Preter m | 995 | Not mentioned | Sunflower seed oil, Mustard Oil | Not mentioned Routine massage practice | Mustard Oil Standard practice | 28 | Oil type may contribute to differences in skin integrity when neonates are massaged regularly. The more rapid acid mantle development observed for SSO may be protective for neonates in lower resource settings |

| Solanki 200516 | Moderate | RCT | Stable neonates three sub-sets viz., (a) gestational age < 34 weeks, (b) gestational age 34–37 weeks, (c) gestati onal age > 37 weeks. | 118 | Hemodynamic mically stable after 3rd day of birth | Safflower oil massage Coconut oil massage | 10 min/session, 4 times per day Trained massager | Only massage | 5 | Topically massaged oil is absorbed significantly in neonates. Types of oil used can alter the lipid profile of the baby and may help in absorption of nutrients Oil application may be considered for reversal of essential fatty acid deficiency in neonates No Adverse reaction |

| Sankaranarayanan 200517 | Moderate | RCT | Full term, Preter m Term births weighing more than 2500 grams | 192 | from day 2 of life | Coconut oil massage Mineral oil massage | 4 Times per day Oil massage was given by a trained person from day 2 of life till discharge, and thereafter by the mother until 31 days of age, | Only massage | 31 | Coconut oil massage has beneficial effects on weight gain in preterm neonates compared to mineral oil massage No significant Neurobehavioral benefits No Adverse reaction |

| Arora 200518 | Moderate | RCT | Medically stable Preter m (Neonates with birth weight < 1500 grams, gestation < 37 weeks) | 62 | Within 10 days of birth | Sunflower oil massage | 10 Minutes/ session 4 times per day. | Without Oil, No massage | 28 | Weight gain in the oil massage group (365.8 + 165.2 g) was higher compared to the only massage group (290.0 + 150.2 g) and no massage group (285.0 + 170.4 g). Since Oil massage is a culturally accepted practice, it should be encouraged as part of early neonatal intervention in very low birth weight infant care both in hospitals and at home |

| Fallah 201319 | High | RCT | Medically Stable Preter m Gestational age: 33–37 weeks, Birth weight of 1500–1999 g, | 54 | Within ten Days of birth | Sunflower oil massage | 3 times per day Mother | Only massage | 14 | In the oil massage group, mean weight at ages 1 month (mean ± SD: 2339 ± 135 vs. 2201 ± 93 g, P = 0.04) and 2 months (mean ± SD: 3301 ± 237 vs. 3005 ± 305 g, P = 0.005) was significantly greater than that of the body massage group |

| Kumar 201320 | High | Cluster RCT | Healthy neonates | n = 26,587 given oil massage 13,478 live-born infants 13,109 infants in the comparis on clusters | applying sunflower seed oil at the first application during the first 6 h after birth, within 7 days of birth | Cold- pressed Sunflower Seed oil massage | 3-times per day using gentle massage with washed hands. | Standard practice of mustard oil, or other prevalent Community practice of Massage | 28 | Weight (g) Weight gain (g) Length (cm) Head circumference (cm) |

Review question: What age is appropriate to start oil massage to infants?

Rationale: