Translate this page into:

Psychological Morbidities and Coping Styles: A Rural Institution-Based Cross-Sectional Comparative Study between Undergraduate Medical Students Undergoing Different Phases of Training

Address for correspondence Sunny Garg, MBBS, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Bhagat Phool Singh Government Medical College for Women, Khanpur Kalan, Sonipat, Haryana 131305, India (e-mail: docter.sunny@gmail.com).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Psychological morbidities are high among undergraduate medical students. They experience the transition between pre-/para-clinical and clinical training as a stressful period, and cope differently. Research studies from India in this regard are lacking.

Aims

The aim of this study is to assess and compare the prevalence of psychological morbidities and their respective associated factors and coping styles between pre-/para-clinical and clinical undergraduate medical students.

Materials and Methods

This institution-based cross-sectional observational design study was conducted among undergraduate medical students (a total of 382) in pre-/para-clinical and clinical years by using a questionnaire in the period between April and June 2019. A stratified random sampling technique was used to select the study participants. The survey included standard self-administered questionnaires like General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) and Lin–Chen's coping inventory to assess psychological morbidities and coping styles, respectively. Associated factors for psychological morbidities and coping styles between two groups were compared using the Chi-square test, independent t-test, and binary logistic regression analysis.

Results

Out of the 382 responders, psychological morbidities (GHQ-28 score > 23) were found in 61% participants. Both groups reported high levels of psychological morbidities; a slightly higher preponderance in clinical (61.5%) than in pre-/para-clinical students (60.6%) with a nonsignificant difference. Compared with the pre-/para-clinical group, the clinical group was found to have more substance consumption behavior (p < 0.001), dissatisfaction with academic performance (p < 0.001), sought psychiatric consultation (p < 0.004), and at that time on psychiatric treatment (p < 0.04). Active problem coping behavior was more significantly used by the pre-/para-clinical group, while passive problem coping and passive emotional coping behaviors were positively significantly correlated with psychological morbidities in the clinical group.

Conclusion

This study suggests a significant correlation between psychological morbidities and passive coping styles in the clinical group. These students need interventions to encourage the use of more active coping styles during training to provide advances in future career. A strong correlation between psychological morbidities and dissatisfied academic performance may be a call for an efficient and more student-friendly curriculum.

Keywords

clinical group

coping styles

pre-/para-clinical group

psychological morbidities

UG medical students

Introduction

The study of medicine including vigorous training schedule is distinctive and more mentally challenging than any other professional courses worldwide.1 Undoubtedly, this unique curriculum in itself is highly stressful,2 and jeopardizes the emotional and mental well-being of students, who develop burnouts throughout the study courses.3,4 Previous literature has confirmed that poor mental health was a predictor of a cascade of psychological morbidities such as depression, anxiety, suicidal behavior, and substance abuse.5,6,7,8 A recent survey in India9 revealed that 60.3% of medical students had psychological morbidities, which was much higher than other studies conducted in the past.10,11,12 This growing evidence of untreated psychological morbidities in medical students is attributed to barriers in seeking psychiatric consultation, which has been a prime concern for mental health authorities.13 A nationwide survey in Brazil14 showed a higher prevalence of psychological problems among first-year medical students as compared with the final-year students, while other authors have reported a notable rise in prevalence with progressing years of study.1,15,16,17

The transition from a theoretical framework to a clinical phase has been identified as a crucial stage in medical training, regarding students' stress.18 Students in clinical training were distinct from pre-/para-clinical undergraduate (UG) students in many ways, and thus are likely to encounter different stressors. The most obvious difference is that all clinical UGs in addition to examination stress also have intense emotional experiences while interacting with dying patients, interpersonal problems with patients, and work overload,19,20 while pre-/para-clinical UGs who tend to be school-passouts or, at most, have taken a “gap year” face a transitional environment of professional college life, which compels them to acquire new skills for peer-competition and difficulties envisaged for integration into the system, separation from family, unlimited parental expectations, and academic stress.21,22 Existing findings in the literature concerning the relationship between psychological morbidities and phase of study are still controversial.20,23,24

At the same time, stress drives medical students to develop certain cognitive skills and behavioral strategies to reduce or tolerate the stressful situations.25 Few studies consistently demonstrated that active coping styles could generate problem-solving behavior and emotion regulations,26 while passive coping skills focused on emotion expression, negative appraisal, and social isolation could enhance the risk of psychological morbidities while confronting stressful situations.27,28 It was noted that self-blame and denial were used mainly by first-year medical students while later year students shifted toward cognitive, confronting, and planned problem-solving strategies.22 In addition to having different and perhaps more severe stressors, given their maturity and greater life experiences, UGs in clinical years are likely to use different coping styles compared with their counterparts but how their respective coping behavior might also differ remains relatively unclear.

There has been extensive research on psychological morbidities, associated factors, and coping styles, and their relationship with year of study in medical students9,10,14,15,16 but the literature is inconsistent in Indian medical students,5 which evaluated and compared the psychological morbidities and coping styles in pre-/para-clinical and clinical group of UGs. These assessments become imperative prior to designing and implementing the interventions to preserve their mental health and reduce psychological morbidities. Therefore, the present study sought to assess and compare the magnitude of psychological morbidities, factors associated with it and the coping styles between pre-/para-clinical and clinical UGs in an institution located in a rural area of northern India. This study also evaluated and compared the association between psychological morbidities and predictors among both the study groups.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Settings

This was a cross-sectional and comparative questionnaire-based descriptive study conducted from April 2019 to June 2019 among UG medical students at a tertiary care teaching institution located in a rural area of a northern state of India. Around 440 students studying in academic year 1 (preclinical) and academic year 2 (para-clinical), which mainly focus on basic science subjects, were enrolled in the pre-/para-clinical group, and students from academic year 3 and academic year 4, which focus on clinical subjects, were enrolled in the clinical group. This study was performed after getting ethical approval from the institutional ethical committee board and in accordance with ethical committee standards and the Helsinki Declaration. During the study, the anonymity and confidentiality of the responses given by the participants were assured and maintained as their personal information like name or contact details were not asked.

Sample Size

The study's required sample size (N = 382) was calculated by using a single population proportion formula. It was calculated on the basis of the following assumptions: nearly 50% of the students would have psychiatric morbidities (P) and the absolute precision is 5% (d) at 95% confidence interval (CI; Z).

Study Sample

Students from all the batches of the UG course, aged 18 years or older (both male and female), able to read and understand English, and willing to give informed consent, were included in the study while internship batch and students not willing to provide informed consent were not included in the study.

Sampling and Data Collection Procedure

A stratified random sampling method was applied to make the strata of the students of each group, and then the total sample size was allocated proportionately to each group of UGs. Finally, a computer-generated random number table was used to select and enlist each study participant to get a calculated sample size of 382 (pre-/para-clinical group: 208 out of 240 students and clinical group: 174 out of 200 students). This sampling method was applied, as the study population was homogenous and readily available. To avoid the effect of examination stress, the questionnaires were distributed among the students 2 weeks before any major class test or examination. The purpose of the study and importance of the honest answers were briefed to the participants, and privacy and confidentiality of their information were also assured. Then, a hard copy of the questionnaire with detachable information sheets about the study was distributed to the selected participants by hand in their classrooms before lectures and during posting hours, and written informed consent was obtained from them before eliciting the required information. All the respondents were instructed that they could ask any question about the study before their participation. At the end of the description, helpline numbers/e-mail addresses were provided for those in need of professional help.

Data Collection Measures

The students were administered with the self-administered, pretested, validated, and semistructured questionnaires which had six sections (1–6), consisting of (1) brief information regarding the study purposes, (2) written informed consent, and (3) the socio-demographic information of the students. Section (4) consisted of questions regarding academic and personal characteristics of the students. Section (5) consisted of 28 questions related to General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) which measures psychological morbidities. The last part of the questionnaire (section 6) had the coping inventory to analyze the coping styles adopted by students. The questionnaires regarding socio-demographic profile and academic and personal profile of the students were created by two authors after an extensive literature research which were pretested and validated.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20

Socio-demographic Profile Pro Forma

It consisted of eight questions—current age, gender (male/female), place of residence where the student was born/raised before entering the course (urban/rural), type of family (nuclear/joint), living status during the course of study (hosteller/day-scholar), average hours of sleep per day (<6 hours or >6 hours), their current substance (tobacco/alcohol/cannabis/opioid) consumption status (yes/no), and physical exercises (<3 days per week or ≥3 days per week).

Academic and Personal Profile Pro Forma

This section of the survey had six questions—academic phase (pre-/para-clinical batch or clinical batch), level of academic performance (satisfied/not satisfied), motive for studying medicine (personal/family pressure), family history of psychiatric illness (yes/no), sought psychiatric consultation during the semester (yes/no), currently taking antidepressant/benzodiazepine/any other psychotropics (yes/no).

General Health Questionnaire-28

It is a validated and standardized self-administered 28-item tool used to identify potential nonpsychotic psychiatric morbidities. The questionnaire refers to the symptoms experienced in the last few weeks, and is therefore an indication of state rather than trait characteristics at a point in time. It has four subscales for the assessment of somatic function (Q1–Q7), anxiety and insomnia (Q8–Q14), social dysfunction (Q15–Q21), and severe depression (Q22–Q28). This is a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, signifying “0 = not at all,” “1 = no more than usual,” “2 = rather more than usual,” and “3 = much more than usual.” The total score ranged from 0 to 84. A cut-off score >23 was used in the present study to define an abnormal GHQ score/probable case.29,30 The Cronbach's α of scale in the present study is 0.860, presenting good internal consistency reliability.

Coping Inventory

The coping techniques employed by the participants were assessed by the coping style inventory developed by Lin and Chen (2010) which consists of 28 items.31 The instruction in the scale given to students was “How do you deal with it when you face problems during this semester?” It was designed as a Likert 5-point scale where scores ranged from 1 to 5 with 1 being “completely disagree” and 5 being “completely agree.” In the present study, minor changes were made in the scale as item number 2, 3, and 18 of the original scale were not much different from other items. So, it was shortened to 25 questions during the content validation phase by two authors, and validated by pilot-testing before use in the current study. This questionnaire was tested on 30 students (15 each from the pre-/para-clinical and clinical groups) as a pilot study. None of these students faced any difficulty in either understanding or answering the questions. Minor changes were suggested in articulation and vocabulary of the items, and changes were made by experts. These responses were not included in the final study. This scale measures four coping behaviors, i.e., active emotional coping (item 1–6), passive emotional coping (7–13), active problem coping (APC; 14–18), and passive problem coping (19–25) behavior. Scores are summed and when it ranged from 25 to 58, then overall coping was rated as poorly adoptive, from 59 to 92 as average, and 93 to 125 as good. The Cronbach's α of this scale in the present study is 0.849, presenting good internal consistency reliability.

Statistical Analysis

The data were entered and analyzed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, United States). Cronbach's α coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency of the scales. Categorical variables were calculated as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were calculated as mean and standard deviations (SDs). Initially, univariate association between psychological morbidities and multiple variables was performed by using the Chi-square test for categorical variables, and independent Student's t-test (parametric) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (nonparametric) for continuous variables. Pearson's correlation test was performed to find out the correlation between the variables and psychological morbidities. Binary logistic regression analysis was applied to explore the contributory factors associated with psychological morbidities. The effect of each of the independent variable was adjusted for few socio-demographic factors that were considered to be potential confounders, viz. current age, gender, residence, type of family, and current living status, in a separate binary regression model. Then, results as adjusted odds ratios and 95% CI were used to evaluate the strength of association between independent variables and psychological morbidities. The statistically significant level was set at p <0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Three hundred and eighty-two medical students were enrolled in the present study. The majority of participants were female (62%; n = 239) and the mean age of the sample was 20.40 (SD = 1.85) years with a range of 18 to 26 years. As expected, the mean age of the clinical group (21.90 years; SD: 1.58) was significantly (p < 0.001) higher as compared with that of the pre-/para-clinical group (19.15 years; SD: 0.87). Most of the respondents in both the study groups were members of nuclear families and coming from rural areas. Around 90% of the students were staying in hostel premises. Further, majority of the students (60%) used to sleep for more than 6 hours per day on an average and did not participate in any physical exercise for ≥3 days/week. Around 29% of the respondents were at that time consuming one or more substance, with a statistically significant higher proportion in the clinical group than the other group of students (38.5 vs. 20.2; p < 0.001) (►Table 1).

| Sr. No. | Variables | Frequency (%) | p-Value (Chi-square) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroups | Total medical students (N = 382) | Pre-/para-clinical group (N = 208) | Clinical group (N = 174) | |||

| 1. | Gender | Female | 239 (62.4) | 129 (62) | 110 (63.2) | 0.809 |

| Male | 143 (37.6) | 79 (38) | 64 (36.8) | |||

| 2. | Residence (born/raised before entering the course) | Rural | 267 (69.9) | 149 (71.6) | 118 (67.8) | 0.418 |

| Urban | 115 (30.1) | 59 (28.4) | 56 (32.2) | |||

| 3. | Type of family | Nuclear | 261 (68.3) | 141 (67.8) | 120 (69) | 0.805 |

| Joint | 121 (31.7) | 67 (32.2) | 54 (31) | |||

| 4. | Living status during the course | Hostel | 345 (90.3) | 191 (90.8) | 154 (88.5) | 0.274 |

| Day-scholar | 37 (9.7) | 17 (9.2) | 20 (11.5) | |||

| 5. | Average sleeping hours per day | <6 h | 152 (39.8) | 82 (39.4) | 70 (40.2) | 0.873 |

| >6 h | 230 (60.2) | 126 (60.6) | 104 (59.8) | |||

| 6. | Do you consume one or more substance (tobacco/alcohol/cannabis/opioid) currently? | Yes | 109 (28.5) | 42 (20.2) | 67 (38.5) | <0.001 a |

| No | 273 (71.5) | 166 (79.8) | 107 (61.5) | |||

| 7. | Exercise status | <3 d/wk | 229 (59.9) | 124 (59.6) | 105 (60.3) | 0.885 |

| ≥3 h/wk | 153 (40.1) | 84 (40.4) | 69 (39.7) | |||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a p < 0.001.

The distribution of responses to the items of academic and personal characteristics of students, shown in ►Table 2, demonstrated that most of the respondents were dissatisfied with their academic performances, while only 12 to 19% of the students cited that they were at that time on psychiatric treatment, sought psychiatric consultation, studying medicine under family pressure, or had family history of psychiatric illness. When the differences between the two groups were evaluated, students in the clinical years had a statistically significant higher proportion with dissatisfied academic performance (72.4 vs. 52.8; p < 0.001), had sought psychiatric consultation during a semester (20.1 vs. 9.6; p = 0.004), and were on psychiatric treatment (16.1 vs. 9.1; p = 0.04).

| Sr. No. | Variables | Frequency (%) | p-Value (Chi-square) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroups | Total medical students (N = 382) | Pre-/para-clinical group (N = 208) | Clinical group (N = 174) | |||

| 1. | Level of academic performance | Satisfied | 142 (37.2) | 94 (45.2) | 48 (27.6) | <0.001 a |

| Dissatisfied | 240 (63.8) | 114 (54.8) | 126 (72.4) | |||

| 2. | Motive for studying medicine | Personal | 317 (83) | 172 (82.7) | 145 (83.3) | 0.868 |

| Family pressure | 65 (17) | 36 (17.3) | 29 (16.7) | |||

| 3. | Family history of psychiatric illness | Yes | 72 (18.8) | 33 (15.9) | 39 (22.4) | 0.103 |

| No | 310 (81.2) | 175 (84.1) | 135 (77.6) | |||

| 4. | Sought psychiatric consultation during this semester | Yes | 55 (14.4) | 20 (9.6) | 35 (20.1) | 0.004 b |

| No | 327 (85.6) | 188 (90.4) | 139 (79.9) | |||

| 5. | Currently on antidepressant/benzodiazepines/any other psychotropics | Yes | 47 (12.3) | 19 (9.1) | 28 (16.1) | 0.04 c |

| No | 335 (87.7) | 189 (90.9) | 146 (83.9) | |||

a p < 0.001.

b p < 0.01.

c p < 0.05.

Psychological Morbidities and Coping Styles

The descriptive statistics on different scales are shown in ►Table 3. When the cut-off of 23 was used for GHQ-28, the overall prevalence of psychological morbidities among the study participants was 61%. The mean score on the GHQ-28 scale was 30.95 (SD =15.39), ranging from 7 to 79, with approximately 60.6% (126) of the pre-/para-clinical group experiencing psychological morbidities, whereas in the other group it was found to be 61.5% (107), with a nonsignificant difference. There was no significant difference between either the total GHQ-28 scores or every subscale mean scores of both groups.

| Sr. No. | Scale | Subscale | Mean (SD); frequency (%) | p-value (t-test/Mann–Whitney U-test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Medical students (N = 382) | Pre-/para-clinical group (N = 208) | Clinical group (N = 174) | ||||

| 1. | GHQ-28 | Somatic functiona | 7.89 (4.24) | 7.95 (4.06) | 7.83 (4.46) | 0.784 |

| Anxiety and insomniaa | 7.89 (5.10) | 7.47 (4.89) | 8.39 (5.31) | 0.081 | ||

| Social dysfunction | 10.17 (3.93) | 10.19 (3.88) | 10.14 (3.98) | 0.893 | ||

| Severe depressiona | 5.01 (4.98) | 4.89 (4.69) | 5.13 (5.32) | 0.644 | ||

| Total GHQ-28 mean score | 30.95 (15.39) | 30.50 (14.75) | 31.48 (16.16) | 0.537 | ||

| 2. | Coping styles | Active emotional coping (AEC) | 23.22 (1.80) | 23.20 (1.68) | 23.25 (1.93) | 0.747 |

| Passive emotional coping (PEC) | 22.46 (3.94) | 22.44 (3.90) | 22.47 (3.99) | 0.939 | ||

| Active problem coping (APC) | 18.01 (1.82) | 17.78 (1.69) | 18.28 (1.92) | 0.007 b | ||

| Passive problem coping (PPC) | 21.87 (3.72) | 21.75 (3.55) | 22.02 (3.90) | 0.482 | ||

Abbreviations: GHQ-28, General Health Questionnaire-28; SD, standard deviation.

a Mann–Whitney U-test (mean < 2 SD).

b p < 0.01.

Overall, the level of coping styles was found to be average among 317 (83%) and good among 65 (17%) participants. The mean score on the coping style scale was 85.59 (SD = 6.87), with a slightly higher value in the clinical years (86.02; SD = 6.54) than in the pre-/para-clinical years (85.17; SD = 7.23). Among the coping styles, only APC was found to be statistically significantly different (p = 0.007) and the least commonly used (17.78; SD = 1.69) coping style among both the study groups, while other coping styles had no statistically significant difference in the mean scores.

Association of Independent Variables with Psychological Morbidities among Study Groups

In intragroup analysis among the pre-/para-clinical group, it was observed that when respondents with and without psychological morbidities were compared for various independent variables, a higher number of students reported psychological morbidities; these students were those who were dissatisfied with their academic performance (74.6 vs. 24.4; p < 0.001), sleeping less than 6 hours/day (56.3 vs. 13.4: p < 0.001), participating in a physical exercise less than 3 days/week (82.5 vs. 24.4; p < 0.001), having family history of psychiatric illness (23 vs. 4.9; p < 0.001), studying medicine under family pressure (24.6 vs. 6.1; p < 0.001), and taking psychiatric treatment at that time (13.5 vs. 2.4; p < 0.01) (not shown in tables). The moderate (r < 0.2–0.4) and strong (r > 0.4) statistically significant positive correlations emerged between these variables and psychological morbidities as depicted in ►Table 4.

| Sr. No. | Variables | Psychological morbidity (r)p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-/para-clinical group | Clinical group | ||

| 1. | Dissatisfied academic performance | 0.493 a | 0.384 a |

| 2. | Substance consumption behavior | 0.112 | 0.335 a |

| 3. | Average sleeping time (<6 hours) | 0.429 a | 0.457 a |

| 4. | Exercise (<3 days/week) | 0.579 a | 0.517 a |

| 5. | Family history of psychiatric illness | 0.243 a | 0.284 a |

| 6. | Sought psychiatric consultation | 0.063 | 0.309 a |

| 7. | Motive for studying medicine (family pressure) | 0.239 b | 0.005 |

| 8. | Currently on psychiatric treatment | 0.287 b | 0.250 b |

| 9. | Passive emotional coping (PEC) | 0.088 | 0.607 a |

| 10. | Passive problem coping (PPC) | 0.050 | 0.221 b |

Note: r = Pearson's correlation coefficient.

a p < 0.001.

b p < 0.01.

Similarly, when respondents in the clinical years with and without psychological morbidities were compared for various independent variables, it was found that a higher number of participants reported psychological morbidities, were dissatisfied with their academic performance (86 vs. 50.7; p < 0.001), consuming one or more substances at that time (51.4 vs. 17.9; p < 0.001), sleeping less than 6 hours/day (57.9 vs. 11.9: p < 0.001), participating in a physical exercise <3 days/week (80.4 vs. 28.4; p < 0.001), having family history of psychiatric illness (31.8 vs. 7.5; p < 0.001), sought psychiatric consultation during a semester (29.9 vs. 4.5; p < 0.001), taking psychiatric treatment at that time (23.4 vs. 4.5; p < 0.01), and used passive emotional coping (PEC) and passive problem coping (PPC) styles as their stress coping behaviors (p < 0.001) (not shown in tables). Moderate (r < 0.2–0.4) and strong (r > 0.4) statistically significant positive correlations were also shown between these variables and psychological morbidities as depicted in ►Table 4.

When independent variables of participants with psychological morbidities between both the study groups were compared, it was seen that statistically significantly a higher number of students in the clinical years were consuming one or more substances at that time (p < 0.001) (►Table 5), dissatisfied with their academic performance (p = 0.031), sought psychiatric consultation during the semester (p < 0.001), and on psychotropics at that time (p = 0.049) (►Table 6). Students in the clinical years obtained a statistically significantly (p = 0.026) higher APC score, whereas students in the pre-/para-clinical years obtained statistically nonsignificant higher AEC and PEC scores, and lower PPC score (►Table 7).

| Sr. No. | Variables | Subgroups | Mean (SD); frequency (%) | p-Value (Chi-square/t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-/para-clinical group (N = 126) | Clinical group (N = 107) | ||||

| 1. | Age (y) | 19.13 (0.90) | 21.80 (1.51) | <0.001 a | |

| 2. | Gender | Female | 80 (63.5) | 68 (63.6) | 0.993 |

| Male | 46 (36.5) | 39 (36.4) | |||

| 3. | Residence (born/raised before entering the course) | Rural | 91 (72.2) | 71 (66.4) | 0.332 |

| Urban | 35 (27.8) | 36 (33.6) | |||

| 4. | Type of family | Nuclear | 84 (66.7) | 73 (68.2) | 0.880 |

| Joint | 42 (33.3) | 34 (31.8) | |||

| 5. | Living status during the course | Hostel | 117 (92.9) | 94 (87.9) | 0.193 |

| Day-scholar | 9 (7.1) | 13 (12.1) | |||

| 6. | Average sleeping hours per day | <6 h | 71 (56.3) | 62 (57.9) | 0.806 |

| >6 h | 55 (43.7) | 45 (42.1) | |||

| 7. | Do you consume one or more substance (tobacco/alcohol/cannabis/opioid) currently? | Yes | 30 (23.8) | 55 (51.4) | <0.001 a |

| No | 96 (76.2) | 52 (48.6) | |||

| 8. | Exercise status | <3 d/wk | 104 (82.5) | 86 (80.4) | 0.671 |

| ≥3 d/wk | 22 (17.5) | 21 (19.6) | |||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a p < 0.001.

| Sr. No. | Variables | Subgroups | Frequency (%) | p-Value (Chi-square test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-/para-clinical group (N = 126) | Clinical group (N = 107) | ||||

| 1. | Level of academic performance | Satisfied | 32 (25.4) | 15 (14) | 0.031 a |

| Dissatisfied | 94 (74.6) | 92 (86) | |||

| 2. | Motive for studying medicine | Personal | 95 (75.4) | 89 (83.2) | 0.146 |

| Family pressure | 31 (24.6) | 18 (16.8) | |||

| 3. | Family history of psychiatric illness | Yes | 29 (23) | 34 (31.8) | 0.131 |

| No | 97 (77) | 73 (68.2) | |||

| 4. | Sought psychiatric consultation during this semester | Yes | 14 (11.1) | 32 (29.9) | <0.001 b |

| No | 112 (89.9) | 75 (70.1) | |||

| 5. | Currently on antidepressant/benzodiazepines/any other psychotropics | Yes | 17 (13.5) | 25 (23.4) | 0.049 a |

| No | 109 (86.5) | 82 (76.6) | |||

a p < 0.05.

b p < 0.001.

| Scale | Subscale | Mean (SD) | Mean difference | SE difference | p-Value (t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-/para-clinical group (N = 126) | Clinical group (N = 107) | |||||

| Coping style | Active emotional coping (AEC) | 23.16 (1.78) | 23.06 (2.04) | 0.106 | 0.250 | 0.670 |

| Passive emotional coping (PEC) | 24.68 (3.14) | 24.31 (3.29) | 0.369 | 0.422 | 0.382 | |

| Active problem coping (APC) | 17.90 (1.82) | 18.45 (1.99) | −0.559 | 0.249 | 0.026 a | |

| Passive problem coping (PPC) | 21.90 (3.70) | 22.70 (4.08) | −0.807 | 0.510 | 0.115 | |

| Total coping styles mean score | 87.65 (6.19) | 88.54 (7.25) | −0.890 | −0.881 | 0.313 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

a p < 0.05.

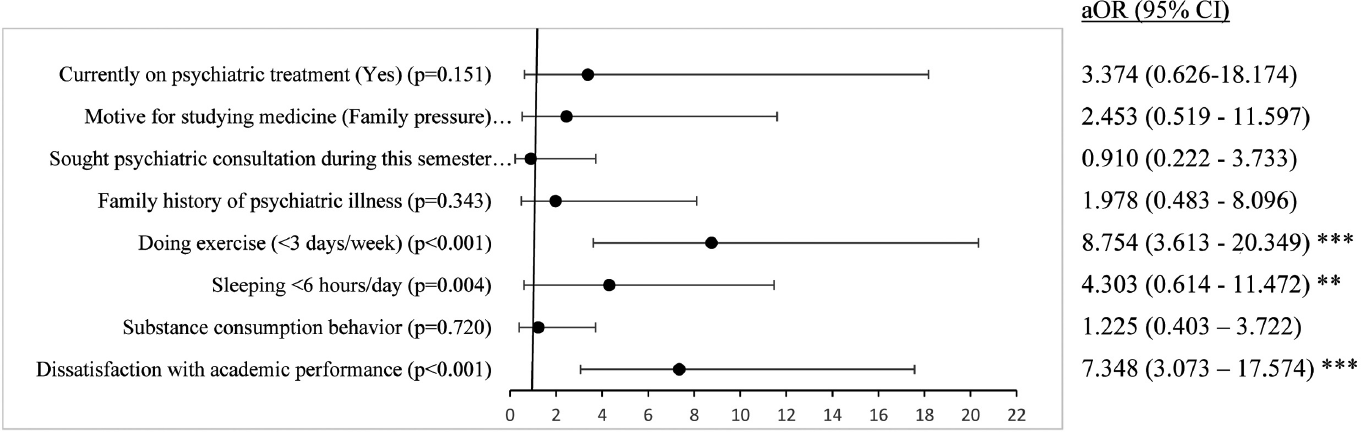

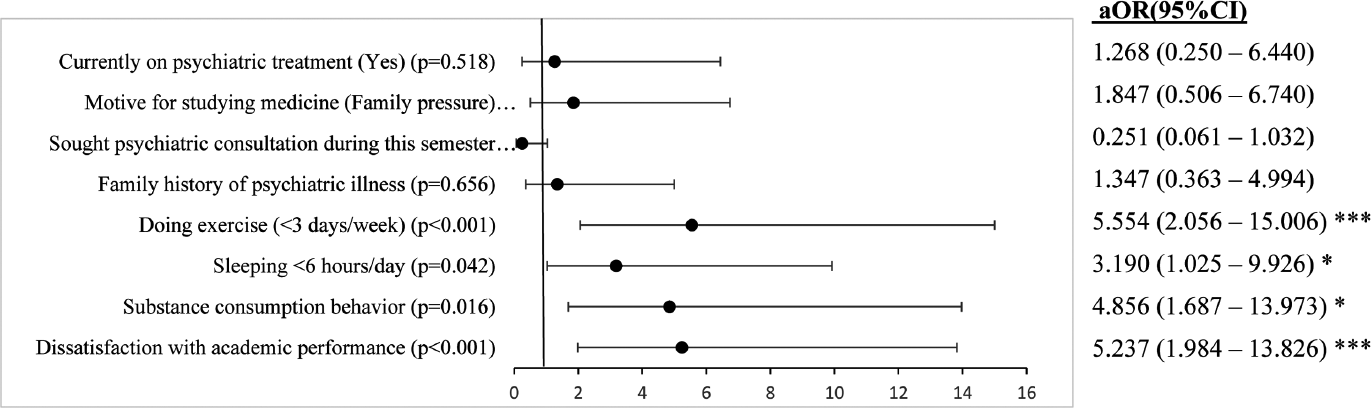

Adjusted Binary Logistic Regression Analysis of Psychological Morbidities in Pre-/Para-clinical and Clinical Groups

The results of cross-sectional association between independent variables and psychological morbidities in both study groups are shown in ►Figs. 1 and 2, which depict sole significant predictors of psychological morbidities. The participants in both the study groups who reported dissatisfaction with academic performance, average sleeping <6 hours per day, and doing physical exercises <3 days/week were found to be more likely to have psychological morbidities. In the clinical years, those students who consumed substances like tobacco, alcohol, opioid, etc. were found to be more likely to have psychological morbidities (p = 0.016) when compared with those who did not consume.

- Forest plot showing binary logistic regression analysis of psychological morbidities in pre-/para-clinical medical students. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; odd ratio adjusted for current age, gender, residence (born/raised before entering the course), type of family, and living status during the course; CI, confidence interval.

- Forest plot showing binary logistic regression analysis of psychological morbidities in clinical medical students. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. aOR, adjusted odd ratio; odds ratio adjusted for current age, gender, residence (born/raised before entering the course), type of family, and living status during the course; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Medical training-related psychological morbidities are a widely known phenomenon, and go conjointly with complexity, obscurity, and challenges of the profession. Keeping this in mind, the present research was conducted using semi-structured instruments to assess and compare psychological morbidities, and their possible association with predictor variables and coping styles. The present study revealed that a staggering 61% of medical students had an abnormal score (>23) on GHQ-28, which is suggestive of higher prevalence of psychological morbidities. Several previous studies from India and other parts of the world9,32,33 lend support to the findings of the present survey and demonstrated a similar higher prevalence of psychological morbidities by using the GHQ-28 scale among medical students. This might suggest a decrease in the psychological health of medical students when one compares the findings of the present study with the studies conducted previously in different areas of the world which evaluated a lower prevalence of psychological morbidities.5,10,21,34,35,36,37 Also, the prevalence of psychological morbidities in the present survey was much higher than the global prevalence estimated by a meta-analysis of medical students in Asia6 and Nigeria.38 These discrepancies might be related to differences in socio-cultural background, sample size, and study design used. The high prevalence of psychological morbidities might be due to significantly higher workload related to academics which leads to burnouts among study participants.

In the present survey, the prevalence of psychological morbidities among pre-/para-clinical and clinical UGs was found to be 60.6 and 61.5%, respectively, but any statistically significant difference in GHQ-28 scores could not be found, suggesting that the rate of psychological morbidities is almost equal in both study groups. This result is in contrast to the findings of a study done by Beniwal et al5 and Konjengbam et al,39 in which the authors as per GHQ-60 and GHQ-12 scales, respectively, observed that the proportion of psychological morbidities among pre-/para-clinical UGs was higher than that of clinical UGs, which was found to be statistically significant. Currently not much data are available within the existing literature for the comparison of psychological morbidities among both the study groups because in most of the previous surveys,14,15,16 the psychological problems faced by the medical students were compared on the basis of their year/semester of study, and also, the other available literature20,23,24,40 compared the psychological distress (using PSS-10 [Perceived Stress Scale] and GHQ-12) rather than psychological morbidities among pre-/para-clinical and clinical UG groups. This finding in the present study might suggest that students have certain common factors related to psychological morbidities but the training-phase factor plays a small role. The slightly higher preponderance of psychological morbidities toward clinical group of UGs is understandable, considering the fact that they are under constant pressure of academics and insecurities about not attaining their goal of being a physician.19,26

The observation of the present survey demonstrated that socio-demographic variables such as age and substance consumption behavior were statistically significant between the comparable groups with psychological morbidities. These results were nearly similar to the observations of few studies done by Mangalesh et al9 and Biswas et al35 in which psychological morbidities among different years of UGs training were statistically significantly associated with age, gender, living status, and substance consumption behavior. Zvauya et al21 and Kiran et al32 also found that psychological morbidities among pre-/para-clinical and clinical UGs were statistically significantly associated with age of the participants. In assonance with the present survey, studies from India32 and another developed country15 had also suggested that with advancement of age and phase of training, the increased academic load and responsibility bestowed upon them engendered stress and made them highly susceptible to psychological morbidities. On the contrary, the cross-sectional survey by Beniwal et al5 pointed out that socio-demographic factors were nonsignificant between the comparable groups with psychological morbidities. Recently, a few authors from India9,35 established a significant association where substance consumption behavior increases five to 10 times odds risk of psychological morbidities among medical educators. The present study also investigated that the substance consumption behavior among clinical UGs significantly increased the propensity of psychological morbidities, having approximately five times higher odds, though it cannot be said for the pre-/para-clinical UGs as the association between psychological morbidities and substance consumption behavior was not statistically significant despite having higher odds (1.25 times). This finding might support the results of other surveys9,41 where it was hypothesized that students in clinical years adopted these detrimental habits in response to their struggles and personal grievances, and need a special mention because of the deteriorating effects on the cognitive functions. Taneja et al42 observed that univariate analysis did not confirm the evidence regarding the significant association between psychological morbidities and substance consumption behavior in medical students, inconsistent with the findings of the present survey.

In the present study, the results yield a significant effect of dissatisfaction of academic performance on the prevalence of psychological morbidities among medical UGs (both groups). These findings align with previous research in the literature which reported that dissatisfaction with academic performance was one of the key factors in inducing the mental health issues among medical students.9,35,43,44 In the present survey, it was also highlighted that students in the clinical group were more in proportion with dissatisfied academic performance than the pre-/para-clinical group, validating the already existing findings where dissatisfaction with academic performance proportionally increased with advancement in phase training.15 This could possibly be due to self-perceived lack of knowledge in clinics, and insecurities about clinical competencies and future careers, leading to fear of failure in exam, due to which students might have feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, and uselessness that ultimately lead to multiple mental health issues. The holistic learning approaches like self-directed learning, acquisition of mentoring support, and reduced stakes on assessment through new medical curriculum might prove promising in alleviating these stresses and associated psychological morbidities in medical UGs.

Previously, it was well established that multiple factors such as stigmatization, denial of mental health problems, informal consultations, concerns about confidentiality, fear of unwanted interventions, and self-diagnosis among medical students were the key influencers on the decision-making process of the student's psychiatric help-seeking behavior.45 The present study suggested that more than three-fourths of students with psychological morbidities are still suffering in silence and notoriously reluctant to seek psychiatric consultation. This finding on the rate of seeking of psychiatric consultation among medical students with psychological morbidities is in the range of previous meta-analysis17 and a study conducted on American surgeons.46 Previously, it was formulated that students in later phases of training got correct knowledge regarding the etiology of psychological problems and psychiatric medicine, which was significantly related to student's disposition to use psychiatric services,47 similar to the results of the present survey where a significant proportion of students in clinical years sought psychiatric help and are currently on psychopharmacotherapies. Accordingly, it can be said that there is a need to initiate psychoeducation program for the medical students at the initial stages of training where “naturalization” of symptoms contributes to nonrecognition of the psychological problems.

The present study is among the firsts to assess how a subset of medical students copes in response to psychological morbidities and how their phase of training affects those coping behaviors. As mentioned in the present study, coping styles adopted by medical students were found to be average among a large number of participants, which was in line with this notion among medical UG students in a midwestern university.4 Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence supporting that the further medical students get in their education, the more emotionally taxing it might be.48,49 This pattern in medical education literature aligns with the observations of the present study where emotional coping styles were used relatively more commonly by the clinical students as compared with another group, while findings revealed by Bamuhair et al22 were inconsistent with this notion. However, a significant positive correlation between psychological morbidities and PEC and PPC scores in clinical years indicates that coping styles adopted by students at a very challenging stage of medical education were not satisfactory and predicts stress in long term. These findings align with reports in the other parts of the world, showing that medical students in later versus earlier years of training tend to use more passive coping strategies, which tend to emanate when stressors are perceived as uncontrollable.50,51 Also, this result is in contrast with few cross-sectional studies done in India51 and United States52 which showed that active-problem coping style was significantly higher in early years of training than in the later years. Hence, how students cope likely depends on the unique environments and stressors they face in each phase of their training.

The main strength of the present study is that this study is, to our awareness, the first to evaluate and compare the psychological morbidities and coping styles in pre-/para-clinical and clinical groups of UGs. Next, the study also helped in finding the vulnerable groups of medical students and phase of medical training by using standardized validated tools with very good internal reliability. Thus, the results observed were intriguing and had effective therapeutic implications in the prevention of psychological morbidities among medical students.

Findings of the present study must be interpreted in light of the limitations of this study. First, it is important to note the inherent limitations of self-reported measures as the rates of psychological morbidities reported in the present study were based on self-reported questionnaires and not on detailed psychiatric evaluations. Second, the present study did not evaluate the specific factors associated with the work-related stress. Third, the present survey performed a cross-sectional assessment which precluded definitive conclusions regarding the direction of causality. Future studies must follow longitudinal study designs to overcome this limitation of the study. Fourth, the study population consisted only of medical students in one institute and therefore may not be extended directly to other settings. Lastly, all the medical UG students were eligible to participate in the study and there were no exclusion criteria. This may lead to a self-selection bias, as medical students with psychological problems may be less motivated to complete the questionnaires, or on the other hand they may be more likely to participate since the topic is relevant to them.

Conclusion and Future Suggestions

The result of the present study reflected that a higher proportion of medical students experienced psychological morbidities. It was also suggested that psychological morbidities are significantly associated with substance consumption behavior and dissatisfaction with academic performance in clinical years. These findings implied that there is an urgent need to develop mechanisms to evaluate other factors associated with psychological morbidities and related targeted measures to decrease substantially the burden of psychological problems on the students. At the same time, there is a need to mitigate stigma associated with mental disorders so that at the time of the need, the students can seek psychiatric help. By broadening the use of psychiatric consultation and adopting more active and less passive coping skills, psychological problems may be prevented or at least diminished among medical students. Stress-reducing techniques and mentoring support need to be encouraged in curriculum, and counselors should be provided for effective addressing and solving the problems.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Association of educational stress with depression, anxiety, and substance use among medical and engineering undergraduates in India. Ind Psychiatry J. 2019;28(02):160-169.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Academic stress and self-regulation among university students in Malaysia: mediator role of mindfulness. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8(01):12-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of academic stress, anxiety and depression with socio-demographic among medical students. Int J Soc Sci Stud. 2018;6:27-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of academic stress and its coping mechanisms among medical undergraduate students in a large midwestern university. Curr Psychol. 2020;40:2599-2609.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mental morbidity among medical students in India. J Med Sci Clin Res. 2017;5:32023-32033.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health issues amongst medical students in Asia: a systematic review [2000-2015] Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(04):72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression and anxiety among undergraduate university students in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2018;7(01):57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review on depression, anxiety and stress among medical students in India. J Mental Health Hum Behav. 2017;22:88-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of mental health in medical students during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;37:105-110.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study of psychiatric disorders in medical science students. Mater Sociomed. 2017;29(03):188-191.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression in students of a medical college in New Delhi: a cross-sectional study. Australas Med J. 2012;5(05):247-250.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health of medical students in different levels of training. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl. 01):S107-S112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression among medical students in Saudi medical colleges: a cross-sectional study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:887-891.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First- and last-year medical students: is there a difference in the prevalence and intensity of anxiety and depressive symptoms? Br J Psychiatry. 2014;36(03):233-240.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depression, stress and anxiety in medical students: a cross-sectional comparison between students from different semesters. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2017;63(01):21-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study of perceived stress among undergraduate medical students of a private college in Tamil Nadu. Int J Sci Res (Ahmedabad). 2015;4:994-997.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214-2236.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among medical students entering clinical training: a three year prospective questionnaire and interview-based study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Students' perceptions about the transition to the clinical phase of a medical curriculum with preclinical patient contacts; a focus group study. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of well-being and coping abilities among medical and paramedical trainees in a government medical college Uttar Pradesh, India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2020;9:229-233.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of stress levels, coping styles and psychological morbidity between graduate-entry and traditional undergraduate medical students during the first 2 years at a UK medical school. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(01):93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sources of stress and coping strategies among undergraduate medical students enrolled in a problem-based learning curriculum. J Biomed Educ. 2015;575139:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of stress levels among medical students, residents, and graduate students at four Canadian schools of medicine. Acad Med. 1997;72(11):997-1002.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of sources and perceived stress between paramedical and medical students. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016;5:183-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Level of stress and coping strategy in medical students compared with students of other careers [in Spanish] Gac Med Mex. 2015;151(04):443-449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(01):38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predicting effects of psychological inflexibility/experiential avoidance and stress coping strategies for internet addiction, significant depression and suicidality in college students: a prospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(04):788-796.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding Singaporean medical students' stress and coping. Singapore Med J. 2018;59(04):172-176.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Health Questionnaire - 28 (GHQ-28) J Physiother. 2011;57(04):259.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of mental health among Iranian medical students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2016;10(01):49-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A stress coping style inventory of student at universities and colleges of technology. World Trans Eng Technol Educ. 2010;8:67-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of psychiatric morbidity among health care students in a teaching hospital, Telangana state: a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study. Indian J Dent Sci. 2017;9:105-108.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression and its associated factors using Beck Depression Inventory among students of a medical college in Karnataka. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54(03):223-226.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological morbidity, sources of stress and coping strategies among undergraduate medical students of Nepal. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiological study on burden of psychological morbidity and their determinants on undergraduate medical students of a government medical college of Eastern India. Indian J Community Health. 2018;30:280-286.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medical students' stress, psychological morbidity and coping strategies: a cross-sectional study from Pakistan. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(01):92-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric morbidity, comorbid anxiety and depression among medical students in public and private tertiary institutions in a Nigerian state: a cross-sectional analytical study. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:53-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health and wellbeing of medical students in Nigeria: a systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(7-8):661-672.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological morbidity among undergraduate medical students. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59(01):65-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sources and severity of perceived stress among Iranian medical students. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(10):e17767.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suicide ideation, attempt, and determinants among medical students Northwest Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19:44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students enrolled in a medical college of New Delhi, India. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;34:157-162.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparing levels of psychological stress and its inducing factors among medical students. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2019;14(06):488-494.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and factors associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms among Palestinian medical students. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(01):244.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian medical students with depression, anxiety and suicidal behavior: Why do they not seek treatment? Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43:1-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(01):54-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing treatment for depression among medical students: a nationwide sample in South Korea. Med Educ. 2009;43(02):133-139.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical student's perceptions of the learning environment in medical school change as students transition to clinical training in undergraduate medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(04):383-391.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How medical students cope with stress: a cross-sectional look at strategies and their sociodemographic antecedents. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(01):299.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behaviour-based functional and dysfunctional strategies of medical students to cope with burnout. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(01):1535738.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional assessment of stress, coping, and burnout in the final-year medical undergraduate students. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25(02):179-183.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical students' use of different coping strategies and relationship with academic performance in preclinical and clinical years. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(01):15-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]