Translate this page into:

Trans-nasal Trans-sphenoidal Endoscopic Hypophysectomy

GOLDEN JUBILEE COMMEMORATION AWARD LECTURE delivered during NAMSCON 2017 at Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, Sri Amritsar, Punjab.

Correspondence : Dr. Saurabh Varshney, Professor & Head, Deptt. of Otorhinolaryngology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh – 249201 (Uttrakhand). Email: drsaurabh68@gmail.com.

Abstract

Advances in optics, miniaturization, and endoscopic instrumentation have revolutionized surgery in the past decades. Current progress in the field of endoscopy promises to further this evolution: endoscopic telescopes and instruments have improved upon the optical and technical limitations of the microscope, and require an even less invasive approach to the sella. The minimally invasive endoscopic pituitary surgery is performed through the natural nasal pathway without any incisions and is performed via Trans-nasal Trans-sphenoidal approach. Pituitary surgery is traditionally within the realm of the neurosurgeon. However, since the introduction of the endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal approach to the sella turcica for resection of pituitary adenoma, otolaryngologists have been active partners in the surgical management of these patients. Otolaryngologists have lent their expertise in nasal and sinus surgery, assisting the neurosurgeon with the operation. The otolaryngologist has the advantage of familiarity with the techniques and instruments used to gain exposure of the sella turcica by transnasal approach. Hence, the otolaryngologist provides the exposure, and the neurosurgeon resects the tumour. Such collaboration has resulted in decreased rates of complication and morbidity.

We hereby discuss our experience of treating 72 cases of pituitary tumour by endoscopic trans-nasal trans-sphenoidal approach. In our study, conducted from 2005 to 2016, the mean age of patients was 32.5 years (18-56 years), Male and female ratio was 1.3:1.0, MRI was done in all the cases, CT scan was done in 94.44 % cases, 9.72% cases had Intra op./ Post op. complications which were managed successfully. Subtotal resection could be done in 6.94% cases, recurrence was seen in 7.46% cases and lumbar drain was required in 4.17 % cases. Average hospital stay was 4.4 days and average surgery time was 120 minutes. Close follow-up was maintained for an average period of 09 months. In our experience of 10 years, adopting the endoscope heightens the surgeons' visualization of pituitary tumors, thus no external incision, no nasal packing and minimal stay with minimal complications. Endoscopic transsphenoidal approach is the less traumatic route to the sella turcica, avoiding brain retraction, and also permitting good visualization, with lower rates of morbidity and mortality.

Keywords

Endonasal

Transnasal, endoscopy

pituitary adenoma

surgical technique, transsphenoidal surgery.

Introduction

Significant advances in the recognition and management of pituitary adenomas have taken place over the last 2 decades. Highly sensitive hormonal assays and magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium enhancement have led to earlier and more frequent diagnosis of pituitary adenomas. Since the early days of pituitary surgery, a variety of transnasal approaches have been used to gain access to the sella turcica. Each of these approaches requires crossing the sphenoid sinus, hence the transsphenoidal designation of these methods (1, 2). The surgical management of pituitary tumors has evolved over time from the transcranial to endonasal transsphenoidal approaches. Endoscopic pituitary surgery is an advancement over the microsurgical technique and has emerged as a better alternative to the microscopic transnasal transsphenoidal (TNTS) technique. An endoscopic transnasal sphenoidotomy approach without a septal dissection for resection of pituitary adenomas and other sellar lesions provided excellent exposure of the sella and adequate working space. The technique produces less postoperative pain and shortens hospital stay (3-6). The sphenoidotomy approach eliminates the problems of lip numbness, septal perforations, and oronasal fistulas. The endoscopic sphenoidotomy approach has become our preferred approach to sellar lesions (7). Endonasal endoscopy can be performed via either one or two nostrils (8-10).

Increasingly, the otolaryngologist is called on to provide exposure for the neurosurgeon performing transsphenoidal hypophysectomy. Multidisciplinary collaborations in managing complex pathologies of the skull base have evolved into a field of “neurorhinology” and this interaction with multiple specialities, notably otolaryngologists and neurosurgeons, has allowed procedures to be developed that offer significant advantages over treatment modalities (11). The team management of pituitary disorders is stressed. We reviewed our series of 72 patients undergoing transnasal hypophysectomy.

History

The evolution of pituitary surgery over the past century dates back to the work of Oscar Hirsch and Harvey Cushing in the early 1900s. Surgical approaches to pituitary adenomas have undergone significant adaptation since the first attempted transcranial and transsphenoidal decompression operations of the early 19th century.

In 1889 Horsley, using a transcranial approach is credited with performing the first operation for a pituitary tumor (12). In 1906 Schloffer reported the first removal of a pituitary tumor through an extracranial transsphenoidal approach (13). Hirsch later modified this approach in 1909. However, it was Cushing's transseptal-transsphenoidal method introduced in 1910, which standardized this approach to pituitary tumors (14). The transseptal-transsphenoidal technique gained popularity throughout the early 1900s. Cushing himself reported on 247 pituitary tumors removed by this method between 1910 and 1929 (15). Inability to reach suprasellar tumor extension, poor illumination, CSF leakage, meningitis, and a high recurrence rate all led Cushing and his contemporaries to abandon the transseptal-transsphenoidal approach by the early 1930s in favor of the transcranial procedure (16).

It is Hardy however, who deserves much of credit for re-establishing the validity of the transsphenoidal approach, when in the 1960s he combined fluoroscopy and microsurgical techniques to further augment transsphenoidal pituitary tumor resection (15, 17). These new technologies provided the transseptal-transsphenoidal approach with significant advantages over the transcranial procedure. The improved visualization, allowed for more complete tumor removal, and reduced the incidence of complications. In the ensuing 40 years several large series have established the transsphenoidal approach as the procedure of choice for all but the most massive pituitary adenomas, demonstrating outcomes equivalent or better than those reported for the transcranial procedure with fewer complications (18, 19).

Microscopic transsphenoidal surgery has long been considered the “gold standard” in surgical treatment of pituitary tumors. The use of rigid endoscopes for sinus surgery provided the inspiration for their application to pituitary surgery (20). In 1992 Jankowski provided the first description of fully endoscopic transnasal-technique (12). At the beginning, the endoscope was mostly used as a microscope-assisted tool to explore the sella cavity for residual tumor. In 1997, the first clinical series of purely endoscopic pituitary surgery was reported by Jho and Carrau. Jho has published relatively large series describing his experience with 44 pituitary adenomas and 6 other parasellar lesions (13). Reports have suggested that in addition to providing more complete tumor removal, the endoscopic technique may also result in a lower incidence of complications related to blind dissection (21-24). Since then, many pituitary surgeons gradually shifted towards an endoscopic endonasal approach for pituitary adenomas and other parasellar tumors. The recent development of endoscopic instrumentations and techniques has contributed in enhancing the efficacy and safety of the endoscopic approach and has further promoted the shift.

Over the last two decades, endoscopic endonasal surgery has gradually gained favor as a primary approach for sellar and parasellar lesions, primarily due to the wide panoramic, up-close visualization offered by the endoscope. Angled endoscopes allow for complete resection of high-grade (invasive) tumors, visualizing parasellar and suprasellar tumor extension, and allowing for rapid decompression of the optic chiasm. Often, the full extent of extrasellar tumor growth is not visible with the direct line of site of the operating microscope (25).

Patients with massive suprasellar tumor extension are recommended to undergo a transcranial approach.

Surgical Procedure

The operation takes place with the patient supine The head of the bed is elevated and the patient's neck is slightly extended and rotated toward the nostril to be used for the procedure. Depending on the pre-operative assessment of the patients nasal passageway a 4 mm endoscope is used. The video monitor is positioned behind the patient's shoulder directly opposite the surgeon's line of vision. The 0° endoscope is used to guide the intranasal dissection and initial tumor resection. Initially sphenoid ostia is identified and sphenoidotomy is done (infero- medially), sella turcica is identified, mucosa over sella is removed and sella bone is removed (using sickle knife/periosteal elevator/drill). Exposed duramater is cauterized and cut in a cruciate manner. After taking tissue for histopathology, tumor resection is carried out using a suction device and ring curettes of varying diameter and orientation (26).

Surgical Steps

The surgical technique includes four stages, namely, the nasal stage, the sphenoidal stage, the sellar stage and the reconstruction stage. Recognition of important landmarks during each of these stages is the key to a safe exposure (Figs. 1- a,b,c,d).

- Four phases / steps of surgical Trans-nasal Trans-sphenoidal Endoscopic Hypophysectomy

- a. Both sides sphenoidal ostia identified (widened), posterior nasal septum (vomer) removed,

- b. Sella turcica bone removed, duramater exposed,

- c. Duramater incised by cruciate incision,

- d. Pituitary Tumour curreted with ring curette and cavity explored.

All operations are performed via a single/double nostril approach. Once tumor resection is complete or residual tumor is outside the field of view, the 0° endoscope is withdrawn and a 30° endoscope is inserted. The angled lens of this endoscope provides excellent exposure of the suprasellar and parasellar regions. Rotating the 30° endoscope clockwise and counterclockwise provides visualization of suprasellar and parasellar tumor extension, including invasion into the cavernous sinus if present. Any residual tumor is resected, eliminating areas of potential tumor recurrence. Once tumor resection is complete, the area is irrigated and hemostasis is obtained.

| Patient Positioning | Patient supine, head of the bed is elevated and the patient’s neck is slightly extended and rotated toward the nostril to be used for the procedure. | |

|---|---|---|

| A. | Nasal stage | Nasal Ethmoid / Turbinate stage |

| B. | Sphenoid stage | Ostium (identification) |

| Sinus (opening) | ||

| C. | Sellar stage | Floor |

| Duramater | ||

| Lesion removal | ||

| Exploration | ||

| D. | Reconstruction | |

An abdominal fat graft is harvested and used to reconstruct the sellar defect, which is then sealed using surgicel and abgel. Nasal packing is done with merocel which is removed after 48 h (24).

Complications and their Avoidance

These can be divided into two major categories: (1) Nonendocrinal; and, (2) endocrinal complications- (27, 28) (Table 1).

| Complications | Causes | Avoidance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonendocrine | |||

| A. Nasal | |||

| Anosmia/hyposmia Saddle nose deformity Epistaxis (early or delayed) | Excessive mucosa coagulation Extended Posterior septectomy Bleeding from posterior septal artery (branch of sphenopalatine artery) | Avoid mucosal coagulation in upper nasal septum of at least 1 cm Avoid excessive removal of cartilaginous nasal septum Bipolar coagulation of posterior septal artery located superolateral to choana, at inferolateral corner of sphenoethmoidal recess, at medial posterior corner of inferior margin of MT | |

| Synechiae/nasal crusting | Raw area/mucosal damage | Keep mucosal damage minimal Leave minimal raw area Remove all foreign material | |

| B. Sphenoidal complications Sinusitis/ mucocele | Improper removal of mucosa | If needed, pack the whole sphenoid, with removal of the entire mucosa Medialize middle turbinate in the end to avoid sinusitis/mucocele | |

| C. Carotid injury | Cavernous segment is most vulnerable | Study preoperative CT, MRI for kissing carotids, anomalous position, and bone dehiscence (20%) Keep always oriented by checking that buttons of the camera are facing the screen Use navigation | |

| D. Cranial CSF leak/meningitis/ pneumocephalus | Inadvertent entry into Anterior Clinoid Process Blind dissecti on Pulling tumor without mobilization | Do not enlarge ostium superiorly No blind dissection to prevent arachoidal tear Tumor should be mobilized first and then sucked in suction Use “flashlight effect” to visualize and differentiate arachnoid from diaphragm If cerebrospinal fluid leak occurs. Immediately seal the rent and reconstruct sellar floor | |

| E. Postoperative apoplexy/ bleed/ swelling/ in residual tumor | Incomplete tumor removal | Always remove maximum tumor Use extended approach with removal of tuberculum sella and m’OCR (cause of constriction) in large Supra sellar extension Use image guidance, angled scope and instruments | |

| F. Sub Arachnoid Haemorrhage and vasospasm | Fixing the scope Arachnoidal tear | use four-hand technique and flashlight effect and avoid arachnoidal tear Do not fix the scope If occurs, seal it immediately with glue and prevent further opening Use cotton patty to cove r the arachnoidal defect to prevent blood going into the subarachnoid space | |

| G. Perforator injury | Blind dissection | Remove tumor under vision, using "flashlight effect” No intra-arachnoidal dissection | |

| H. Decreased vision | Avoid overzealous sellar packing Maximal tumor resection to avoid postoperative apoplexy | ||

| I. Hydrocephalus | Remove maximal tumor/avoid arachnoidal tear | ||

| Endocrine | |||

| Worsening/ new endocrine dysfunction | Damage to normal pituitary | Always predict position of normal pituitary in preoperative MRI Intraoperatively- it is pinkish, firm, nonsuckable, with presence of vasculature on surface Thinned out residual normal pituitary tissue appears as an apron plastered to the unde rsurface of diaphragm Normal pituitary should be preserved (even 10% is enough) | |

Materials and Methods

Surgery for pituitary tumours was performed by rhinosurgical route by combined procedure by otolaryngologist and neurosurgeons. A retrospective review of case records of patients who had endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for pituitary tumours under general anaesthesia from 2005 to 2016 was performed. A total of 73 transphenoidal surgeries were performed during this study period. Only 72 case records with adequate information were available for review, which were for primary 68 (94.4%) or recurrent pituitary adenomas (05.6%).

Observations

The mean age of patients was 32.5 years (18-56 years). There were 41 females (56.94%) and 31males (43.06%). Female and male ratio was 1.3:1.0. In our series, the peak age was fifth decade (50-60 years) accounting for 28 (38.9%) patients. Endocrinal status was assessed and medical fitness for surgery was ascertained. Out of total 72 pituitary adenomas, 58 (80.5%) were hormonally active (functional), while 14 (19.5%) were non-functioning. 68 (94.4%) were macroadenoma (> 10 mm), and 04 (5.6%) were microadenoma (< 10 mm). 38 patients (55.88%) out of 68 macro-adenoma had suprasellar extensions.

Other than hormonal symptoms the most common presenting complaints included visual symptoms—changes in visual acuity or visual field deficits (61) (84.72%) headache (56) (77.77%) menstrual cycle disturbance or infertility /impotence (18) (25%), and acromegalic features (16) (22.22%).

Preoperative magnetic resonance (MR) imaging were obtained in all the patients, and CT scans were obtained in 68 (94.44%) patients. The exquisite definition of the bony boundaries of the sinus, provided by thin-sliced axial and coronal computerized tomography (CT) scans, was essential to assess the symmetry and aeration of the sphenoid sinus and to decipher the relationship of the sphenoid sinus septum to the sella turcica floor and carotid canals. The operation was performed under general anesthesia has been induced in the patient via orotracheal intubation. Intranasal packing was occasionally used and removed on the second post-operative day. Only 03 patients (4.17%) had lumbar drain inserted prior to commencement of the surgery and all these were macroadenomas.

Subtotal resection could be done in 5 (6.94%) cases with residual tumor in the cavernous sinus. Recurrence was seen in 5/67 (7.46%) cases, Five of the patients demonstrating recurrent tumor had a mass ranging from 5 to 8 mm on an MRI scan performed postoperatively, two of them underwent revision surgery and 3 of them having recurrence were referred for Gamma knife surgery. 07cases (9.72%) had Intra op./ Post op. complications which were managed successfully. The common complications encountered were Nasal synechae- 03 (4.16%), diabetes insipidus- 1 (1.39 %), cerebrospinal fluid leak-1(1.39%), epistaxis- 1 (1.39 %)- postoperative sphenopalatine bleed, septal perforation-1 (1.39%). The CSF leaks were controlled by vascularized mucosal flaps which hastens the healing process. Hadad nasoseptal flap, supplied by the posterior nasoseptal arteries which are branches of the posterior nasal artery was used in 01 case. There was no mortality in our series.

Average hospital stay was 4.4 days and average surgery time was 120 minutes. Close follow-up was maintained for an average period of 09 months The most common indications for longer hospitalization included temporary diabetes insipidus and prior co-morbid conditions which required extended monitoring or rehabilitation. Patient outcomes were determined from intra-operative assessment of tumor resection, postoperative hormonal levels and MR imaging results. MR imaging studies were performed for all patients during the early postoperative period, to be repeated after 6–12 months and then annually for the rest of their follow-up period. Remission, being defined as no hormonal or radiological evidence of recurrence within the time-frame of the follow-up. Remission was demonstrated in 62/72 (86.1%) of adenomas.

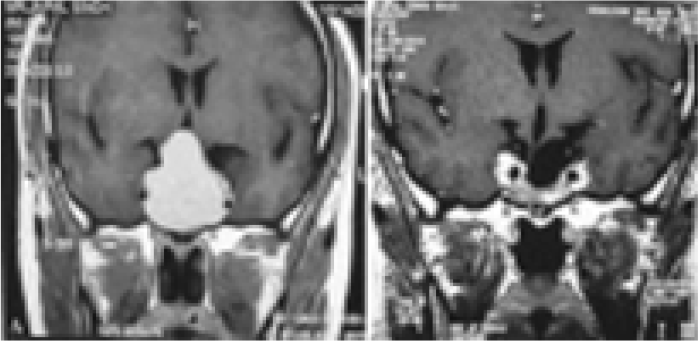

- Coronal MRI brainshowing pituitary tumour

- Sagittal MRI brainshowing pituitary tumour

- Sagittal MRI brain- showing pituitary tumour (pressing on optic chiasma)

- Pre op. MRI (a) and Post op. MRI (b) after 6 months

Discussion

Microsurgical transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma has been the standard treatment for decades in the neurosurgical community (2, 8). Jankowski et al. first reported the successful endonasal endoscopic resection of pituitary adenomas in three patients. They removed the middle turbinate to gain access to the sphenoid sinus. They performed the operation via one nostril in two patients and via both nostrils in another (12). Sethi and Pillay reported approximately 40 patients in whom they had performed endoscopic pituitary surgery via either the transnasal transseptal or ethmoidectomy approach with a sphenoid retractor (14). The use of thin-sliced axial and coronal CT scans is essential to avoid unexpected findings from anatomical variations in the sphenoid sinus. Magnetic resonance imaging alone will not provide the necessary detail of bone anatomy of the sphenoid sinus.

In general, pituitary adenomas are diagnosed more frequently in women than in men probably because of the association of these tumours with menstrual irregularities (11) which correlates with our study. The incidence of pituitary adenoma increases with age, peaking between the third and sixth decades (11). In our series also, the peak age was fifth decade (50-60 years) accounting for 28 (38.9%) patients.

Pituitary adenoma can be divided into functioning and non functioning tumours, or according to size namely microadenomas or macroadenomas. Functioning pituitary adenomas can be clinically classified by means of the hormone they secrete. These tumours become symptomatic because they secrete hormones such as growth hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and prolactin.

The incidence of residual tumour is higher in pituitary macroadenoma. This is probably due to size and extension of tumour to surrounding structures namely suprasellar extension to optic chiasm and lateral extension to engulf the internal carotid artery. Twenty eight percent of pituitary macroadenomas can extend into the carvernous sinus as reported in the literature (29). Complete removal in macroadenoma may be difficult without adequate decompression. In our series, Subtotal resection could be done in 5 (6.94%) cases with residual tumor in the cavernous sinus. Recurrence was seen in 5/67 (7.46%) cases.

Complications of endoscopic surgery of the paranasal sinuses can be classified according to the severity as minor or major and according to the time of appearance as immediate or delayed. Minor complications occur in between 2 and 21% (30) of cases which include synechiae, crusts, minor bleeding, nasal septum perforation, headache, facial pain, alteration of dental sensitivity, edema, local infection, periorbital ecchymosis, palpebral edema, subcutaneous emphysema, stenosis of sinus ostia, hyposmia, epiphora, exacerbation of bronchial asthma, and postoperative sinusitis, this goes in coherence with our study (9.72%). The principal major complications anticipated are vascular injury and orbital and intracranial complications which vary from 1 to 3% (Table 2). The most frequent immediate complications are CSF leak, intraoperative bleeding, orbital hematoma and injury to brain (27, 28). Delayed complications include progressive loss of vision (24) or smell, meningitis, bleeding, synechiae, and infection.

| • Poor general condition of patient |

|---|

| • Conchal type of sphenoid pnematization |

| • Sphenoid sinus infected |

| • Highly vascular lesions |

| • Dural-based lesions with a high risk for intraoperative and postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak |

| • Extensive suprasellar extension and carotid artery anatomy, wherein the arteries project into the sphenoid sinus and limit safe access |

| • Multi Septate Sphenoid |

Future Advances

Over the past several years, endoscopic technology, instrumentation, and relevant anatomical mastery have promoted many innovative methods and approaches to the extrasellar regions. The new developed instrumentations include high definition 3D endoscopic system, (31) endoscopic augmented reality navigation system, (32) ultrasonography-assisted endoscope, (33) the indocyanine green fluorescence endoscope, (34) and use of high-field intraoperative MRI, (35) et al. These are reported to increase the safety and reduce the risk of the endoscopic approach (Table 3). Recently, an experimental feasibility study on robotic endonasal telesurgery was reported (36). 4K (and 8K) ultra-high definition endoscopes are likely to be introduced to this field in the near future (14).

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Better illumination and superior visualization as the light source is close to the target | Endoscope provides a two dimensional (2D) vision |

| Wide angle view and visualization of the opticocarotid recess (OCRs) as well as carotid and optic protuberances | Spatial distortion of the periphery of the image occurs |

| Angled endoscopes expand the range of visualization including visualization of corners and hidden angles permitting complete removal of the tumor | It has limited zoom and focus capability |

| A high image resolution permitting more accurate differentiation between the diaphragm sellae and the arachnoid, and between the normal and neoplastic tissue enabling preservation of normal pituitary | The 3–4 handed technique requires two surgeons |

| Avoidance of nasal speculum and packing causes less postoperative discomfort and an early return to work | The operating time is longer in the initial phase of the learning curve |

The extended endoscopic surgery to the midline ventral skull base have been extensively developed and refined for removal of parasellar tumors including supasesellar adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, chordomas, chondrosarcomas, meningiomas, et al. The advantages and benefits of the endoscope can be more appreciated in the extended surgery for these parasellar tumors than the pituitary surgery (37).

Conclusion

Currently, the Transnasal-Transsphenoidal (TNTS) hypophysectomy approach represents the standard approach by which the vast majority of pituitary adenomas are surgically resected. Endoscopic pituitary surgery is useful in all micro-and macropituitary adenomas including those with suprasellar and cavernous sinus extension. The endoscope provides a panoramic close-up, a multi-angled view with excellent illumination and magnification, permitting complete excision of the tumor with preservation of normal pituitary and a reduced incidence of complications. The results of this fully endoscopic transnasal series are quite encouraging. We echo the statements of Jho regarding the challenges to successful outcomes: “Certainly, a learning curve exists for a surgeon who is not familiar with the endoscope. A surgeon inexperienced with this technique may become frustrated if the two instruments consistently strike each other in the small operating space (38). Traditionally pituitary tumours have been removed by neurosurgeons through the cranial approach but the advent of nasal endoscopes has opened new avenues for ENT surgeons to treat such patients (39). We believe that the inherent advantages of endoscopic visualization, along with continued refinement of the endoscopic technique and instruments will allow this method to become the future gold standard surgical approach to pituitary adenomas.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest, no commercial relationships, no support from pharmaceutical or other companies. The author has no personal or institutional financial interest in drugs, materials, or devices described in the present paper.

Acknowledgement

The major part of the work was done at my previous institute- Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, Dehradun

References

- Transnasal transsphenoidal hypophysectomy: choice of approach for the otolaryngologist. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120(6):824-827.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The rhinologist and the management of pituitary disease. Laryngoscope. 1979;89(Suppl 14):1-26. 2 Pt 2

- [Google Scholar]

- Extended applications of endoscopic sinus surgery-the territorial imperative. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:313-315.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic management of lesions of the sella turcica. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:956-962.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic anatomy of the sphenoid sinus and sella turcica. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:951-955.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The endoscopic approach to the sphenoid sinus. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:218-221.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic sphenoidotomy approach to the sella. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(3):602-607.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to the sella: towards Functional Endoscopic Pituitary Surgery. Minim Invas Neurosurg. 1998;41:66-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The use of the rigid endoscope in transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:19-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A direct transnasal approach to the sphenoid sinus. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:140-142.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic pituitary tumor surgery. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(198–20):2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopy assisted transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma. Technical note. Acta Neurochir. 1996;138:1416-1425.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultra-high definition (8K UHD) endoscope: our first clinical success. Springerplus. 2016;5:1445.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the efficacy of endoscopy in pituitary adenoma resection. Archives Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:1487-1490.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pituitary tumors. A borderland between cranial and transsphenoidal surgery. N Engl J Med. 1956;254:937-939.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The evolution of transsphenoidal pituitary microsurgery. Surgery. 1986;100:1185-1190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pituitary tumors: current concepts in diagnosis and management. West J Med. 1995;162:340-352.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transphenoidal microsurgery of the normal and pathological pituitary. Clin Neurosurg. 1969;16:185-217.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complications of transsphenoidal surgery: results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:225-236.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The evolution of transsphenoidal pituitary microsurgery. Surgery. 1986;100:1185-1190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visual deterioration after trans-sphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma-a rare but severe complication: case report with review of literature (case report) Indian J Otolaryngol and Head Neck Surg 2005 (special issue: 179–181)

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic Trans Nasal Trans-Sphenoidal (TNTS) Approach for Pituitary Adenomas: Our Experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65(Suppl 2):308-313.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic pituitary surgery: Techniques, tips and tricks, nuances, and complication avoidance. Neurol India. 2016;64:724-736.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complication of endoscopic pituitary surgery and their avoidance. In: Mishra BK, Laws ER, Kaye AH, eds. In: Currents Progress in Neurosurgery. Mumbai: Tree Life India; 2014. p. :46-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of pituitary tumors and other abnormal intrasellar masses. Retrospective analysis of 353 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78(4):236-269.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A direct transnasal approach to the sphenoid sinus. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:140-142.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three-dimensional endoscopic pituitary surgery. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5 Suppl 2):288-293.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic augmented reality navigation system for endonasal transsphenoidal surgery to treat pituitary tumors: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1393-1397.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endonasal ultrasonography-assisted neuroendoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015;157:863-868.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usefulness of the indocyanine green fluorescence endoscope in endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:1185-1192.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Use of high-foeld intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging during endoscopic transphenoidal surgery for functioning pituitary macroadenomas and small adenomas located in the intrasellar region. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2013;53:501-510.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An experimental feasibility study on robotic endonasal telesurgery. Neurosurgery. 2015;76:479-484.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent Evolution of Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery for Treatment of Pituitary Adenomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2017;57(4):151-158.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic pituitary surgery: an early experience. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:213-223.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craniopharyngioma - Transnasal Endoscopic Approach. Online J Health and Allied Sciences. 2010;9(4):1-3.

- [Google Scholar]