Translate this page into:

Using the Immune System to Manage Immunologically-Mediated Pregnancy Loss

Address for correspondence Raj Raghupathy, PhD, FRCPath, Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Jamal Abdul Nasser St, 13110, Kuwait (e-mail: raj.raghupathy@ku.edu.kw).

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Pregnancy is not nearly as successful as laypersons might assume, challenged as it is by several complications such as threatened abortion, spontaneous miscarriage, preeclampsia, and preterm delivery, among others. The maternal immune system has been shown to contribute to the etiopathogenesis of some of these pregnancy complications. Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines have been studied for their effects on pregnancy because of their powerful and versatile effects on cells and tissues. This review addresses the relationship between pro-inflammatory cytokines and recurrent miscarriage, which is an important complication of pregnancy. References for this review were identified by using PRISMA-IPD (Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data) Guidelines by conducting searches for published articles from January 1, 1990 until March 1, 2020 in the following databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, and MEDLINE via OVID by the use of the search terms “recurrent spontaneous miscarriage,” “cytokines,” “progesterone,” “progestogen,” “dydrogesterone,” and “immunomodulation.” This review also presents the proposed mechanisms of action of pro-inflammatory cytokines in pregnancy loss, and then goes on to discuss the modulation of cytokine profiles to a state that is favorable to the success of pregnancy. In addition to its indispensable endocrinologic role of progesterone in pregnancy, it also has some intriguing immunomodulatory capabilities. We then summarize studies that show that progesterone and dydrogesterone, an orally-administered progestogen, suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhance the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines before mentioning clinical studies on progestogen supplementation. These studies support the contention that progestogens should be explored for the immunotherapeutic management of pregnancy complications.

Keywords

pregnancy

recurrent spontaneous miscarriage

progesterone

dydrogesterone

immunomodulation

Introduction

Our immune system with its exquisite specificity and versatile capabilities is what stands between us and the bewildering range of pathogens. The immune system manages to prevent a whole host of foreign invaders such as viruses and bacteria from infecting us using its arsenal of innate and adaptive immunity, molecules like antibodies, complement, and cytokines, and cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and granulocytes. However, much as the immune system serves as a protective defense barrier, it is also responsible for adverse reactions such as autoimmune diseases and hypersensitivities. One such problem, based on the interactions between the immune system and the reproductive system, occurs when the immune system interferes with fertilization and causes autoimmune infertility.1,2 Another problem is the sometimes adversarial effect that the maternal immune system has on pregnancy. Several potential complications may arise between the long period of pregnancy from fertilization to delivery; these include threatened miscarriage, spontaneous miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, preterm rupture of fetal membranes, and preterm delivery. A large number of studies have examined the roles of the maternal immune system in contributing to the pathogenesis of many of these conditions but in this review, we will focus on the immunology of spontaneous miscarriage.

Methodology of the Review

A comprehensive search strategy was used to identify articles relevant to this review. Literature searches were done by using PRISMA-IPD (Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data)3 in the following databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, and MEDLINE via OVID. These searches were conducted by the first author (S.R.) and then examined by both authors (S.R. and R.R.). References for this review were identified by searches from January 1, 1990 until March 1, 2020 by the use of the search terms “recurrent spontaneous miscarriage,” “cytokines,” “progesterone,” “progestogen,” “dydrogesterone,” and “immunomodulation.” Only articles in English were included. The articles included original research papers and reviews.

Recurrent Spontaneous Miscarriage

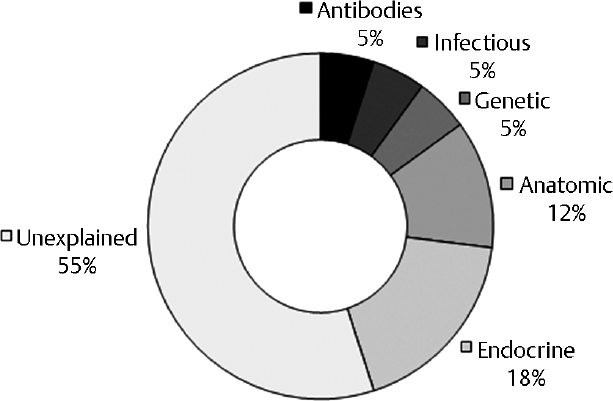

Spontaneous miscarriage, defined as a pregnancy loss in the first 20 weeks of gestation, occurs in one out of every four pregnant women. Recurrent spontaneous miscarriage (RSM) is the occurrence of two or more pregnancy losses prior to the 20th week of gestation and is one of the most challenging disorders of pregnancy.4 It may come as a surprise that despite decades of research only 40 to 50% of the cases of RSM are due to “known” causes such as chromosomal abnormalities, endocrinologic aberrations, infections, and anatomical problems.5 As much as 60% of the cases of RSM are due to “unknown” or “unexplained” etiologies (►Fig. 1).4 Thus the cause of RSM has remained unexplained in a majority of the cases and this has stimulated research into possible immunologic etiologies of RSM. Immunologists have played valuable roles in research in obstetrics and gynecology, by exploring immunologic factors that may be responsible for RSM unexplained in terms of genetic, infectious, and endocrinologic factors.

- Etiologies of recurrent spontaneous miscarriage.

Immunologic Etiologies of Recurrent Spontaneous Miscarriage

Both humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity have been investigated as possibly contributing to RSM. Interestingly, the fetoplacental unit is resilient to attack by humoral immune factors except for anti-phospholipid antibodies which are clearly implicated in a proportion of RSM.6

Much attention has been focused on cell-mediated immune effectors as possible etiologic factors; these include maternal T lymphocytes, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells in maternal peripheral blood and in uteroplacental tissues. A significant boost to research in this area came from the revolutionary discovery of the different subsets of T helper (Th) lymphocytes and the cytokines produced by them. As important effectors of cell-mediated immunity, cytokines have received a great deal of attention in the field of maternal–fetal immunology.

What are Cytokines?

What are cytokines and what is the relevance of cytokines to pregnancy and to pregnancy loss? Cytokines are the most crucial mediatory molecules of the immune system; they play extremely vital roles as communication signals primarily between cells of the immune system, and also between other cells in the body. Cytokines are pluripotent mediators of an impressive range of immune responses including the initiation and sustenance of normal immune responses to infections, rejection of allografts, autoimmune diseases, and hypersensitivity.7,8

Cytokines synthesized and secreted by immune cells such as Th lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells have been studied extensively in the context of the maternal–fetal relationship. Th1 and Th2 cells are the major subsets of Th cells, with different patterns of cytokine production and thus different roles in immune responses.9,10 Th1 cells secrete the cytokines interferon (IFN) γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-β, TNF-α, and interleukin (IL)-2; these so called Th1 cytokines stimulate and maintain strong cell-mediated and inflammatory reactions such as cytotoxicity and delayed-type hypersensitivity. These inflammatory cytokines mediate graft rejection, autoimmune disease pathology, and inflammatory tissue damage. On the other hand, Th2 cells secrete the cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 which stimulate robust antibody production. Th1 and Th2 cells are mutually antagonistic to each other; some Th1 cytokines suppress the activation and/or the function of Th2 cells and vice versa.9,10

Cytokines and Pregnancy Loss

Healthy pregnancy is associated with a natural pregnancy-induced immunomodulation in which there is a downregulation of Th1 responses and upregulation of Th2 responses, manifested as a suppression of cell-mediated immunity and an enhancement of humoral immunity.11,12,13 Indeed, cellular immunity mediated by effector cells and/or cytokines released by them have been demonstrated to harm the conceptus. The administrations of single low doses of the inflammatory Th1 cytokines TNFα, IFNγ, and IL-2 into pregnant mice cause abortions while the injection of anti-TNFα antibodies reduces abortion rates in a murine model of natural, immunologically-mediated abortion.14 TNFα and IFNγ block the outgrowth of human trophoblast cells in vitro15 and synergistically induce the apoptosis of human primary villous trophoblast cells.16

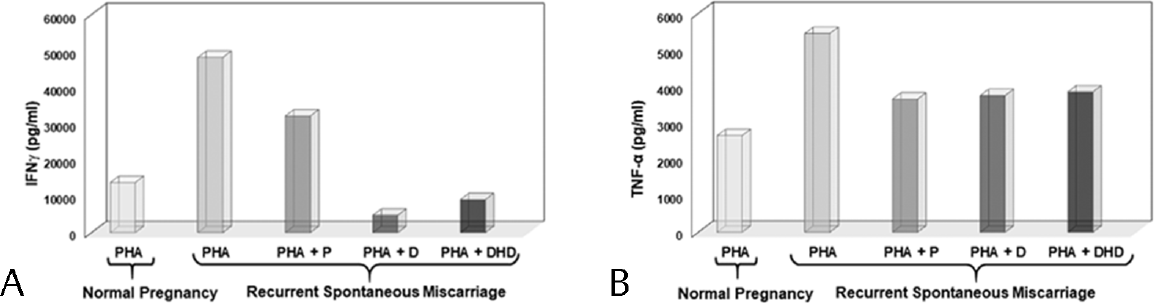

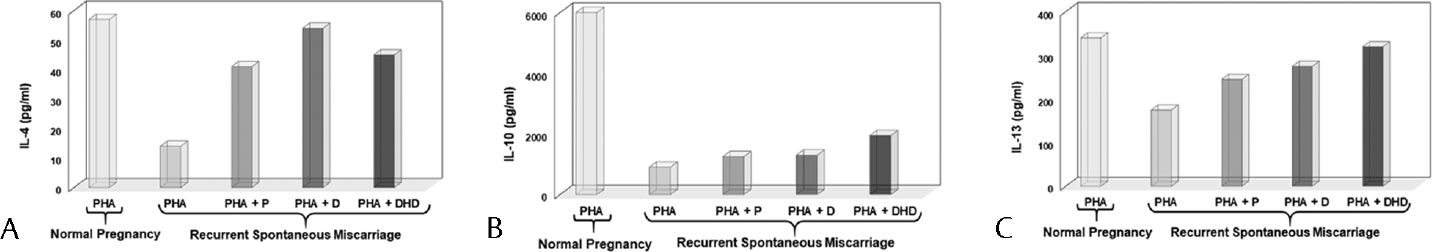

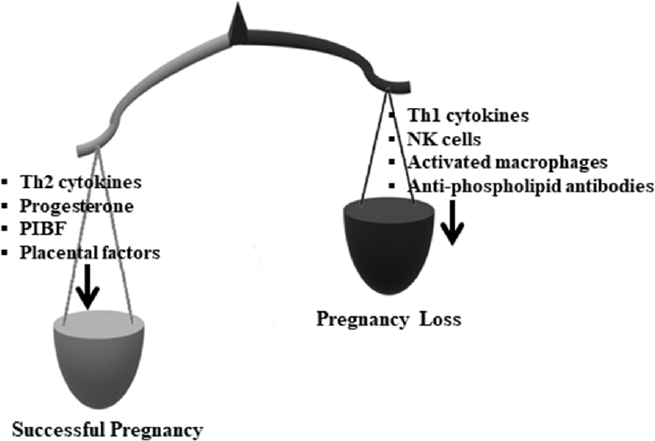

Considering that pro-inflammatory or Th1 cytokines have so many cytotoxic and tissue-damaging effects, as well as anti-pregnancy capabilities, it is not surprising that unexplained RSM is associated with a greater bias toward Th1or pro-inflammatory cytokines.17 Peripheral blood cells from women with a history of RSM when stimulated with human trophoblast antigens were shown to secrete much higher levels of Th1 cytokines with embryotoxic activity.18 We have demonstrated that mitogen-stimulated peripheral lymphocytes from women with a history of healthy pregnancy produce significantly higher levels of the anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10; on the other hand, women with unexplained RSM produce significantly elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-2, IFNγ, and TNF-α (►Figs. 2 3).19,20 We went on to confirm this by studying maternal immune reactivity to placental antigens stimulated either by co-culturing maternal lymphocytes with autologous placental cells and by exposing maternal lymphocytes to a trophoblast antigen preparation.21 The ratios of inflammatory cytokines to anti-inflammatory cytokines were higher in women undergoing RSM compared with women undergoing healthy pregnancy; this supports the contention of Th1 or pro-inflammatory cytokine dominance in RSM as opposed to a stronger Th2-bias in healthy pregnancy.22 Marzi and colleagues studied cytokine production 1 to 2 weeks before any upcoming pathology could be detected; they found decreased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 and increased production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and IL-2 by antigen-stimulated lymphocytes from women with RSM as opposed to those from normal pregnancy.23

- Effects of progestogens on Th1 cytokine production. Effects of progesterone (PHA+P), dydrogesterone (PHA+D), and dihydrodydrogesterone (PHA+DHD) on the production of IFN-α (A) and TNF-α (B) by peripheral blood lymphocytes stimulated with a mitogen (PHA). The levels of these two inflammatory Th1 cytokines are higher in recurrent miscarriage than in normal pregnancy and these are suppressed by progesterone (P), dydrogesterone (D), and dihydrodydrogesterone (DHD). IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

- Effects of progestogens on Th2 cytokine production. Effects of progesterone (PHA+P), dydrogesterone (PHA+D), and dihydrodydrogesterone (PHA+DHD) on the production of IL-4 (A), IL-10 (B), and IL-13 (C). The levels of these three anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokines are lower in RSM than in normal pregnancy, and progesterone, dydrogesterone, and dihydrodydrogesterone increase the levels of IL-4 and IL-13. DHD, dihydrodydrogesterone; IL-4, interleukin-4; RSM, recurrent spontaneous miscarriage.

The situation in the maternal periphery is mirrored by developments in the local environment, i.e., at the maternal–fetal interface; lower levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine-producing T cell clones were found in the decidua of women with unexplained RSM than in the decidua of women with normal pregnancy.24 Endometrial expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines are upregulated, and anti-inflammatory cytokines downregulated, in women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage as compared with controls.25 Most reports thus support the notion that women with recurrent miscarriage have increased levels of Th1 cytokines, while women with healthy pregnancy have decreased levels of Th1 cytokines and increased levels Th2 cytokines; there is thus an increased pro-inflammatory cytokine bias in unexplained recurrent miscarriage.17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25

Mechanisms of Cytokine Action in Recurrent Miscarriage

Pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines have been reported to mediate damage to the fetoplacental unit in different ways. NK cells in the blood and the uterus show elevated levels and activity in RSM; NK cells, like activated Th1 cells, produce cytokines that are known to be injurious to the trophoblast.26 Th1 cytokines also have the ability to convert NK cells into lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells that have been shown to lyse trophoblast cells; systemic levels of LAK-like cells correlate with high miscarriage rates.27 Hill explains that a Th1-dominated response could be detrimental to early placental differentiation and growth and thus harm embryonic development.28 Decidual NK cells are not cytotoxic, but secrete high levels of the Th1 cytokine IFNγ29 which activates decidual macrophages which are known to kill trophoblasts.30

TNF-α and IFNγ both Th1 inflammatory cytokines kill trophoblast cells by apoptosis, and may thus directly damage the conceptus18,31 and also inhibit the secretion of the growth-stimulating cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor which contributes to the growth of placental cells. A potent mechanism of damage to the placenta was described by Knackstedt and colleagues32 who termed it “cytokine-triggered vascular autoamputation”; they showed that Th1 cytokines activate coagulation mechanisms that can lead to vasculitis which limits blood supply to the implanted embryo.

Manipulation of Cytokine Profiles

If pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with recurrent miscarriage, can we downregulate these cytokines, and upregulate the beneficial anti-inflammatory cytokines? This would help create a milieu that is conducive to the success of pregnancy. This rationale is already being used successfully for diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis33 and inflammatory bowel disease34 using antibodies to cytokines and/or cytokine receptors. In the field of maternal–fetal immunology we can consider the use of the pregnancy-related hormone progesterone, which fascinatingly enough has been shown as early as in 1983, to have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties.35 Progesterone is of course indispensable for the establishment of the receptive endometrium and this has been known for a long time; what is less widely known is that progesterone contributes immunologically to the success of pregnancy by interacting with the maternal immune system. In fact progesterone was referred to as “Nature's immunosuppressant” 43 years ago, based on studies that demonstrated immunosuppressive properties of progesterone.36 Progesterone suppresses the activation and proliferation of lymphocytes,37 suppresses the oxidative burst of activated monocytes, and has been shown to prolong the survival of allografts when administered locally.38

Modulation of Cytokine Profiles by Progestogens

Considering that pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with recurrent pregnancy loss on the one hand17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and that progesterone has interesting immunomodulatory capabilities,35,36,37,38 it stands to reason that progestogens can be considered for downregulating Th1/pro-inflammatory cytokine reactivity.

A landmark study showed that progesterone inhibits the production of Th1 cytokines by trophoblast antigen-activated peripheral blood cells from women with unexplained RSM.39 In addition to progesterone we have also investigated the immunomodulatory capabilities of dydrogesterone (6-dehydro-9β, 10α-progesterone) (Duphaston®, Abbott Laboratories, United States), an orally-administered progestogen, which is similar to endogenous progesterone in its molecular structure and pharmacological effects, but more potent than natural progesterone, with a high affinity for the progesterone receptor.40

We studied the production of cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated with a mitogen; we observed that in the presence of dydrogesterone or progesterone, PBMCs from women with a history of unexplained RSM produce significantly lower levels of the Th1 (pro-inflammatory) cytokines IFNγ and TNFα as compared with women with a history of healthy pregnancy (►Fig. 2). On the other hand, levels of the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-6 were significantly elevated in the presence of dydrogesterone or progesterone (►Fig. 3).41 We found a significant reduction in Th1/Th2 cytokine ratios upon exposure to dydrogesterone, indicating a decrease in dominance of Th1 or pro-inflammatory cytokines. We also showed that the progesterone-receptor antagonist RU486 mitigates the effects of dydrogesterone and progesterone indicating that the effect of dydrogesterone and progesterone is mediated via the progesterone receptor.41

Several studies have focused on the potent pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 secreted by a subset of T lymphocytes called Th17. IL-17 is a powerful chemoattractant and activator of monocytes and neutrophils. The administration of IL-17 into pregnant mice leads to embryonic loss indicating that this inflammatory cytokine is antagonistic to pregnancy.42 Increased levels of IL-17 have been observed in the peripheral blood and decidua of recurrent aborters.43 The incidence of uRSM is associated with an increase in the level of serum IL-17 and the number of Th17 cells in peripheral blood.44 We have recently demonstrated that dydrogesterone also suppresses the production of this inflammatory cytokine.45 Thus, dydrogesterone suppresses not just Th1 cytokines but also the Th17 cytokine, IL-17.

Thus, dydrogesterone has potent immunomodulatory properties; however, we were concerned about the fact that soon after ingestion, dydrogesterone is converted into 20[α]-dihydrodydrogesterone (DHD); in circulation dydrogesterone is actually present as DHD. Interestingly, we found that this metabolite also inhibits the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and TNFα and upregulates the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 showing that major metabolite of dydrogesterone retains the immunomodulatory effects of the parent molecule dydrogesterone.46 which is an important feature if we are to consider dydrogesterone as a potential therapeutic immunomodulator. Progesterone has also been shown to preferentially support the development of human T cells producing Th2 cytokines in vitro leading to the inference that progesterone promotes fetal survival by inducing the production of Th2 cytokines.24 Subjects with a history of recurrent miscarriage having higher levels of serum progesterone were shown to have lower Th1/Th2 cytokine ratios suggesting that progesterone levels modulate cytokine production patterns in vivo.47

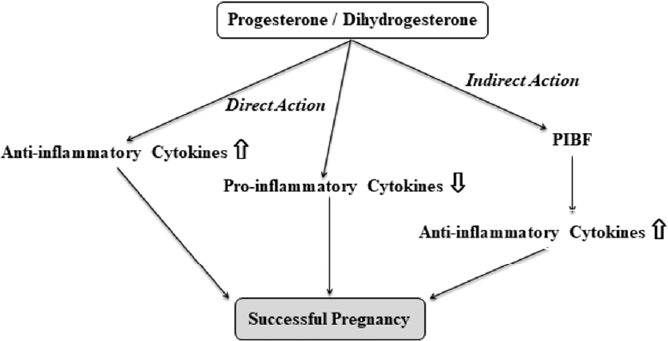

Progesterone modulates cytokine production profiles in a direct manner as described above; however, it is also capable of indirectly modulating cytokine profiles via a protein called progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF) discovered by Szekeres-Bartho et al 35 years ago.48 Fetal wastage induced by the transfer of NK cells into mice is reversed by the administration of PIBF.49 The blocking of endogenous PIBF with anti-PIBF antibodies, or the inhibition of PIBF synthesis by blocking progesterone receptors results in Th1-dominant cytokine production, significantly increased NK activity, and fetal loss which is corrected by the treatment with anti-NK antibodies.50

PIBF is present in human serum and urine during normal gestation but urinary PIBF levels fail to increase in pathological pregnancies as they do in normal gestation.51 Failure to detect PIBF at 3 to 5 weeks of gestation was shown to be associated with a higher rate of miscarriage.52 Treatment of women undergoing threatened miscarriage with dydrogesterone proved to be beneficial; this was associated with increased levels of PIBF and it appears to be mediated through cytokines.53 We have observed that PIBF induces a Th2-dominant cytokine response, by facilitating the production of IL-4 and IL-10, thus altering the Th1/Th2 balance in favor of pregnancy.54

The cytokines IFNγ and TNFα that are downregulated by dydrogesterone and progesterone are the very mediators that are detrimental to the development of the embryo, implantation, and trophoblast proliferation15 and that are toxic to trophoblast cells.16 These two inflammatory cytokines cause fetal death when injected into pregnant mice.14 Thus, the ability of progestogens to inhibit the production of these inflammatory cytokines can be expected to be conducive to the success of pregnancy (►Fig. 4).

- The impact of cytokines, progesterone, PIBF, and other factors and cells on the success of pregnancy. Other immunological and nonimmunological factors, of both maternal and placental origins, have been shown to influence pregnancy, but these are not discussed in this review. PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor.

Supplementation with Progesterone and Dydrogesterone: Clinical Applications

Supplementation with oral progesterone, compared with no treatment or treatment with a placebo, has been shown in Cochrane reviews to result in a reduction in miscarriage rate.55,56 A systematic review of progesterone supplementation in RSM has shown a significant beneficial effect.57 Moreover, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial showed that progesterone supplementation results in significantly lower miscarriage rate, enhanced live birth rate, and increased rate of pregnancy continuation beyond 20 weeks. Administration of progesterone in the luteal phase of the cycle before confirmation of pregnancy in women with history of unexplained RM reduces the risk of miscarriage.58 Progesterone is currently being used in assisted reproductive technology to reduce the occurrence of miscarriage chiefly for threatened and/or recurrent miscarriage.59 Choi et al have proposed that progesterone may benefit women in whom the etiology of RSM is related to maternal Th1 cytokine predominance.39

However, while supplementation with progesterone is beneficial, orally-administered progesterone is absorbed poorly, is subject to first-pass mechanism, has a short biologic half-life,60 loses much of its bioactivity,61 and is cleared quickly.62 On the other hand, the orally-active progestogen dydrogesterone is highly selective for the progesterone receptor is thus a more attractive alternative as it circumvents these drawbacks.40 As mentioned earlier, dydrogesterone retains its immunomodulatory activity even after it is converted to its major metabolite after oral administration.46 Another important feature of dydrogesterone is that its anti-androgenic properties avoid the masculinization of female fetuses and reduces the chances of insufficient masculinization of male fetuses.63

Several researchers have reported that supplementation with dydrogesterone is beneficial in recurrent miscarriage. El-Zibdeh observed that dydrogesterone-treated women with unexplained RSM had fewer miscarriages compared with placebo controls.64 An important randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on dydrogesterone supplementation by Kumar et al recently demonstrated a significant decrease in the number of miscarriages as well as an increase in the mean gestational age at delivery.65 On the basis of a systematic review of randomized trials on dydrogesterone, Carp66 concluded that supplementation with dydrogesterone results in a 13% absolute reduction in the miscarriage rate, with minimal side-effects. The results of this systematic review demonstrate a significant reduction of 29% in the odds for miscarriage as compared with conventional care, thus confirming a real treatment effect.

Summary and Future Perspectives

The data presented in this review indicate that dydrogesterone, a progestogen that is widely used for progesterone-related endocrinologic disorders of pregnancy, may find use from an immunologic perspective as well. Dydrogesterone shifts the balance from a Th1 or pro-inflammatory cytokine dominance toward a Th2 or anti-inflammatory bias; this is a cytokine pattern that is favorable to the success of pregnancy (►Fig. 5). Thus, dydrogesterone may be considered for effective, safe, and orally-administered therapeutic intervention in unexplained RSM.

- Summary of direct and indirect mechanisms of the immunological actions of progestogens on pregnancy.

Recent evidence suggests that dydrogesterone may be well worth considering for therapeutic or preventive intervention in other pregnancy complications such as preterm delivery and pre-eclampsia both of which have been shown to be linked to increased Th1 reactivity.13,67,68,69,70 We have demonstrated that dydrogesterone suppresses the production of Th1 cytokines and upregulates the production of Th2 cytokines by lymphocytes from women undergoing preterm delivery.71 A recent study showed that the administration of dydrogesterone in women at risk for preterm labor resulted in increased production of Th2 cytokines and PIBF, as well as decreased production of Th1 cytokines, suggesting that it could be considered for prevention or treatment of preterm labor and delivery.72 Similarly, supplementation with dydrogesterone from 6 to 20 weeks of pregnancy significantly decreased the incidence of pre-eclampsia in women with high-risk pregnancy.73 Thus, while this review focuses primarily on recurrent miscarriage, recent evidence suggests that dydrogesterone can be considered for the prevention and/or treatment of two other major complications of pregnancy: preterm delivery and pre-eclampsia.

The fact that dydrogesterone has a well-established safety profile in addition to its attractive feature of being orally administered makes dydrogesterone a promising candidate for immunomodulation of pregnancy complications.

Authors' Contributions

S.R. conducted the literature review, prepared the figures, and drafted the manuscript; R.R. prepared and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Autoimmune primary ovarian insufficiency. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4-5):427-430.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of antisperm antibodies in infertility, pregnancy, and potential for contraceptive and antifertility vaccine designs: research progress and pioneering vision. Vaccines (Basel). 2019;7(03):116.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA-IPD Development Group. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1657-1665.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recurrent pregnancy loss. In: Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Creasey RK, Resnik R, Iams JD, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, Greene MF. eds Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier-Saunders; 2014:108-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41(01):157-166.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiphospholipid syndrome and recurrent miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Reprod Immunol. 2017;123:78-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Historical insights into cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(suppl 1):S34-S45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytokines and their role in health and disease: a brief overview. MOJ Immunol. 2016;4(2):00121.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- T helper cytokine patterns: defined subsets, random expression, and external modulation. Immunol Res. 2009;45(2-3):173-184.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon. Immunol Today. 1993;14(07):353-356.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy: success and failure within the Th1/Th2/Th3 paradigm. Semin Immunol. 2001;13(04):219-227.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(06):601-610.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Control of fetal survival in CBA x DBA/2 mice by lymphokine therapy. J Reprod Fertil. 1990;89(02):447-458.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effects of soluble products of activated lymphocytes and macrophages on blastocyst implantation events in vitro. Biol Reprod. 1991;44(01):69-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic effects of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon -γ on cultured human trophoblast are modulated by fibronectin. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6(07):635-641.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunological modes of pregnancy loss: inflammation, immune effectors, and stress. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72(02):129-140.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trophoblast apoptosis is increased in women with evidence of TH1 immunity. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(04):1047-1049.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytokine production by maternal lymphocytes during normal human pregnancy and in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(03):713-718.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitogen-induced cytokine responses of maternal peripheral blood lymphocytes indicate a differential Th-type bias in normal pregnancy and pregnancy failure. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;42(05):273-281.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal Th1- and Th2-type reactivity to placental antigens in normal human pregnancy and unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortions. Cell Immunol. 1999;196(02):122-130.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Th1 and Th2 cytokine profiles in recurrent aborters with successful pregnancy and with subsequent abortions. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(10):2219-2226.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of type 1 and type 2 cytokine production profile in physiologic and pathologic human pregnancy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106(01):127-133.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- T helper cell mediated-tolerance towards fetal allograft in successful pregnancy. Clin Mol Allergy. 2015;13(01):9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of key contributory factors responsible for vascular dysfunction in idiopathic recurrent spontaneous miscarriage. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80940.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural killer cells in female infertility and recurrent miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(03):429-438.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decidual natural-killer-cell interaction with trophoblast: cytolysis or cytokine production. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28(02):196-198.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal-embryonic cross-talk. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;943:17-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(09):656-663.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FasL on decidual macrophages mediates trophoblast apoptosis: a potential cause of recurrent miscarriage. Int J Mol Med. 2019;43(06):2376-2386.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of tumour necrosis factor-α in combination with interferon -γ on first trimester extravillous trophoblast invasion. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;88:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Th1 cytokines and the prothrombinase fgl2 in stress-triggered and inflammatory abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2003;49(04):210-220.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2328-2337.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inflammatory bowel disease therapy: blockade of cytokines and cytokine signaling pathways. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34(04):187-193.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Differential actions of progesterone and cortisol on lymphocyte and monocyte interaction during lymphocyte activation—relevance to immunosuppression in pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 1983;5(04):215-228.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progesterone and maintenance of pregnancy: is progesterone nature's immunosuppressant. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1977;286:384-397.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progesterone modulation of pregnancy-related immune responses. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1293.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppression of immune responses by progesterone. Endocrinol Exp. 1980;14(01):27-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progesterone inhibits in-vitro embryotoxic Th1 cytokine production to trophoblast in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(suppl 1):46-59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progestational effects of dydrogesterone in vitro, in vivo and on the human endometrium. Maturitas. 2009;65(suppl 1):S3-S11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of cytokine production by dydrogesterone in lymphocytes from women with recurrent miscarriage. BJOG. 2005;112(08):1096-1101.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IL-17 induces fetal loss in a CBA/J×BALB/c mouse model, and an anti-IL-17 antibody prevents fetal loss in a CBA/J × DBA/2 mouse model. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75(01):51-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased prevalence of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in peripheral blood and decidua in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion patients. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;84(02):164-170.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alteration of Th17 and Treg cells in patients with unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion before and after lymphocyte immunization therapy. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12(74):74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of progesterone, dydrogesterone and estrogen on the production of Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines by lymphocytes from women with recurrent spontaneous miscarriage. J Reprod Immunol. 2020;140:103132.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of cytokine production by the dydrogesterone metabolite dihydrodydrogesterone. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;74(05):419-426.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altered crosstalk of estradiol and progesterone with myeloid-derived suppressor cells and Th1/Th2 cytokines in early miscarriage is associated with early breakdown of maternal-fetal tolerance. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019;81(02):e13081.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progesterone-treated lymphocytes of healthy pregnant women release a factor inhibiting cytotoxicity and prostaglandin synthesis. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol. 1985;9:15-18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIBF: the double edged sword. Pregnancy and tumor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;64(02):77-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progesterone in pregnancy: endocrine-immune cross talk in mammalian species and the role of stress. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:268-279.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urinary progesterone-induced blocking factor concentration is related to pregnancy outcome. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(05):1699-1705.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miscarriage in the first trimester according to the presence or absence of the progesterone-induced blocking factor at three to five weeks from conception in progesterone supplemented women. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2005;32(01):13-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of dydrogesterone supplementation on hormonal profile and progesterone-induced blocking factor concentrations in women with threatened abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;53(04):166-171.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF) modulates cytokine production by lymphocytes from women with recurrent miscarriage or preterm delivery. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;80(1-2):91-99.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progestogen for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD003511.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Progestogen for treating threatened miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:CD005943.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progestagen therapy for recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14(01):27-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peri-conceptional progesterone treatment in women with unexplained recurrent miscarriage: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(03):388-394.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of progesterone therapy in early pregnancy: from physiological role to therapeutic utility. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(06):421-424.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacokinetics of progesterone administered by the oral and parenteral routes. J Reprod Med. 1999;44(suppl 2):141-147.

- [Google Scholar]

- The absorption of oral micronized progesterone: the effect of food, dose proportionality, and comparison with intramuscular progesterone. Fertil Steril. 1993;60(01):26-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bioavailability of oral micronized progesterone. Fertil Steril. 1985;44(05):622-626.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dydrogesterone use in early pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(02):97-106.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dydrogesterone in the reduction of recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97(05):431-434.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral dydrogesterone treatment during early pregnancy to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss and its role in modulation of cytokine production: a double-blind, randomized, parallel, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(05):1357-1363.e3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of dydrogesterone for the treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(06):422-430.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pro-inflammatory maternal cytokine profile in preterm delivery. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2003;49(05):308-318.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Th1:th2 dichotomy of pregnancy and preterm labour. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:967629.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytokines as key players in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(Suppl. 01):8-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redirection of cytokine production by lymphocytes from women with pre-term delivery by dydrogesterone. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58(01):31-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dydrogesterone and pre-term birth. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2016;27(03):81-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of progestogen supplementation (dydrogesterone) in the prevention of preeclampsia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;26:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]