Translate this page into:

Rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia in a patient with abdominal tuberculosis

*Corresponding author: Dr. Kundan Mishra, Department of Hematology, Research and Referral, Army Hospital, Delhi, India. Email: mishrak20@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Boddu R, Sharma A, Mishra K, Kumar S. Rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia in a patient with abdominal tuberculosis. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci (India). 2024;60:26-9. doi: 10.25259/ANAMS-2022-3-9-(585)

Abstract

Most anti-tubercular drugs are relatively safe, but adverse reactions are not uncommon. Rifampicin is one of the most effective and widely used anti-tuberculosis drugs. Adverse effects due to rifampicin are not uncommon and the patients usually have skin rash, gastrointestinal disturbances, and hepatotoxicity. Rarely, the patients may also have allergic and autoimmune manifestations, which may include life-threatening thrombocytopenia. A high index of suspicion and careful evaluation for temporal association with the suspected drug are required to diagnose drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. We present a case of rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia; though relatively rare, it needs attention.

Keywords

ATT

Rifampicin

Thrombocytopenia

Tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis has a high prevalence rate in India, and its treatment has been a therapeutic challenge because of non-compliance and side effects of anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) drugs. Rifampicin is among the most effective and widely used anti-tuberculosis drugs. Adverse reactions (ADR) due to rifampicin are common, and the patients usually have skin rash and gastrointestinal disturbances, but rarely require stoppage of the drug.1 Hepatotoxicity is another frequent ADR and may require the substitution of the drug with other second-line agents. Rarely, the patients may also develop allergic and autoimmune manifestations, like acute renal failure and thrombocytopenia.2 Thrombocytopenia may be life-threatening and can be seen with several ATT drugs, including rifampicin.3,4 It is typically reversible if diagnosed early and treated appropriately. We report a case of rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia, presented with severe bleeding manifestations, and recovered after the drug was substituted from the treatment regimen.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old girl with no prior comorbidities, presented with complaints of low-grade fever, abdominal pain, and loss of appetite for two months. She also had a history of weight loss of 4–5 kg during this period. On examination, she had subcentimetric level-III cervical lymphadenopathy. Her vitals were stable, and detailed systemic evaluation performed was non-contributory. On evaluation, her hemoglobin (Hb) was 7.5 g/dL, white blood cells/total cell count (WBC/TLC) was 6,800/cmm, and platelet count was 2,82,000/cmm. Renal and liver function tests were normal. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) images of the abdomen showed moderate ascites and thickening of the ileocaecal region with subcentimetric lymphadenopathy. Ascitic fluid analysis showed a WBC of 5,600/cmm with lymphocyte predominance (80%). Ascitic fluid for acid-fast bacilli was negative, but adenosine deaminase was elevated at 78.6 U/L(<40 U/L). Based on clinical and radiological findings, she was diagnosed with abdominal tuberculosis. She was started on ATT (thrice weekly isoniazid 300 mg, rifampicin 450 mg, ethambutol 800 mg, and pyrazinamide 1,000 mg) with pyridoxine 40 mg under directly observed treatment short-course (DOTS) category I. She tolerated the treatment well, became asymptomatic in the next two weeks, and was discharged on ATT.

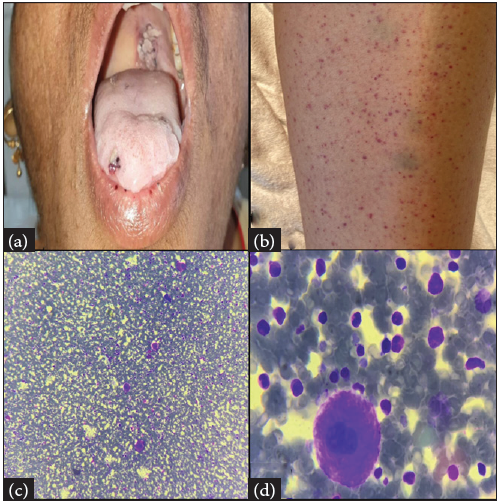

Four weeks later, she presented with skin rashes over bilateral extremities and the lower lip [Figures 1a, 1b]. She also had gum bleeding for the last three days. Her detailed clinical examination revealed multiple palpable, non-blanching purpura over bilateral lower limbs and trunk. Examination of the oral cavity revealed a wet purpura on the soft palate.

- (a–b): Clinical photograph showing petechiae over (a) Lower lip; (b) Lower limb; (c–d): Bone marrow aspirate showing trilineage hematopoiesis with increased Megakaryocytes (c) 100x and (d) 1000x.

Her investigations showed low hemoglobin (Hb-6.9 g/dL), low platelet (platelet-4,000/cmm), and normal (WBC-6700/cmm). Peripheral blood smear (PBS) showed predominantly normocytic normochromic red blood cells and severe thrombocytopenia, with no evidence of schistocytes. Dengue profile, HIV, hepatitis viral serology, and antinuclear antibody (ANA) profile were negative. The reticulocyte count was 0.8%. Bone marrow aspirate revealed normocellular marrow with megakaryocytic hyperplasia. No evidence of any atypical cells or blasts in the marrow [Figures 1c–1d]. Before considering the diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), drug-induced thrombocytopenia (DITP) was thought of, as the patient was on ATT.

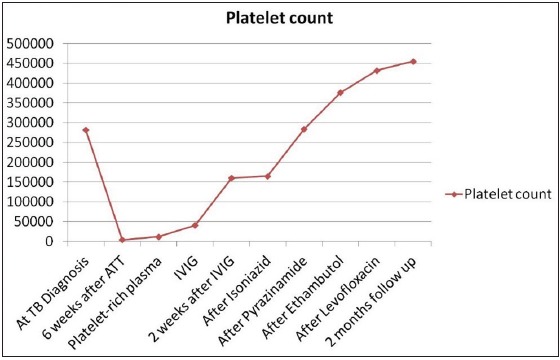

The ATT was stopped with a suspicion of DITP, as her platelet count was normal before the initiation of ATT. Because of wet purpura, she was immediately transfused with platelet-rich plasma followed by intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG-1g/kg). Two days later, the platelet count showed an increasing trend. In the next two weeks, she had a platelet count of 160,000/cmm. After complete recovery of the platelet, ATT was restarted. Considering the assumed rifampicin toxicity, it was omitted from the regimen. Modified ATT was initiated, and one drug was introduced at one time, starting with isoniazid. Pyrazinamide was added seven days later, followed by ethambutol and levofloxacin in that order. The patient is planned for nine months of modified ATT. The platelet count showed an increasing trend thereafter and subsequently became stable after achieving normal levels [Figure 2].

- Trend of platelet count during the course of the treatment (ATT: Anti tubercular therapy; IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin).

Rifampicin was subtracted from the regimen, and in two weeks the platelet count became normal and remained stable thereafter. The current platelet count on follow-up is 455,000/cmm. There were no other clinical, hematological, or biochemical abnormalities during the follow-up examinations.

DISCUSSION

Though anti-tubercular drugs are considered relatively safe, serious adverse events are also well known. All the first-line ATT drugs are known to cause thrombocytopenia. However, it is relatively common with rifampicin and is extremely rare with isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Thrombocytopenia is among the rare yet life-threatening adverse effects seen with rifampicin.5 Thrombocytopenia arising due to induced rifampicin was reported way back in 1970.6 However, it is relatively rare, as reported by Tuberculosis Research Centre, Chennai, over 30 years among 8,000 patients treated; only a single case of rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia was noted.7 However, in a subsequently reported review, rifampicin was one of the most common drugs reported as the cause for thrombocytopenia.8 Thrombocytopenia as an ADR is usually associated with intermittent or high-dose rifampicin regimen.9 The postulated hypothesis is that continuous exposure to the drug results in the neutralization of antibodies, whereas in others (intermittent regimen) a sufficient quantity of antibodies are built up during the drug-free interval so that when the drug is re-administered, a strong reaction takes place.10,11 Also noted is the occurrence of ADR significantly correlates with the presence of drug-dependent (rifampicin-dependent) antibodies.12 However, the occurrence of thrombocytopenia with a daily regimen cannot be completely ignored and has been previously reported.13 Our patient also had thrombocytopenia on a continuous regimen (daily rifampicin) and it occurred 6 weeks after she was started on rifampicin.

Several drugs other than ATT are well-known causes of thrombocytopenia. They are heparin, quinine, sulfonamides, vancomycin, piperacillin, ampicillin, and some herbal medicines.2 Concomitant use of these drugs should also be excluded during evaluation. These drugs cause thrombocytopenia either by suppression of platelet production or immunological destruction, the latter being the most common mechanism.8 In the presence of offending antigen (drug), the immune complexes nonspecifically attach to the platelet membrane, and this results in platelet damage and their rapid clearance from the peripheral circulation.5 In rifampicin-induced immune thrombocytopenia, the most important target is the binding site located in the glycoprotein GPIb/IX.14 Confirmation of DITP at presentation is often difficult, as the tests for drug-dependent antiplatelet antibodies are not readily available. George et al., defined standard criteria for diagnosing DITP after a thorough evaluation of the literature.15 The four criteria are: (1) The offender drug not only preceded the thrombocytopenia but also the drug withdrawal led to complete and sustained recovery of the platelet count. (2) The offender drug was the only drug used prior to the thrombocytopenia onset, or any other drugs used were continued (or reintroduced) after discontinuation of the offender drug with a persistent normal platelet count. (3) Any other cause of low platelet count was excluded. (4) Re-introduction of the offender drug resulted in the re-occurrence of thrombocytopenia. In the present case, three out of four criteria are met suggestive of probable DITP. The patient was not re-exposed to the offending drug, as even a miniscule quantity of the drug is sufficient to set up a severe immune reaction as reported in some of the published literature.11,16

DITP, though fatal, is a potentially reversible adverse effect. The index case had wet purpura, a sinister sign suggestive of impending intracranial hemorrhage.3 There is an urgency to increase platelets in these cases. After stopping the offending drug, platelet transfusion, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin are used alone or in combination.8,17 The benefit of platelet transfusions remains unclear, as it has not been studied in any clinical trial. Further, the majority of the drugs are cleared from circulation within a few hours to a few days, and platelet counts often start to rise within days to weeks after discontinuing the offending drug. Rarely, low platelet count and bleeding manifestations persist for up to a month or longer. A high index of suspicion and early stoppage of suspected drugs are necessary to overcome this potentially fatal adverse effect.

CONCLUSION

The case highlights the need for suspicion, confirmation, and corrective measures to be taken in the case of drug-induced thrombocytopenia.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Antituberculosis drugs: Drug interactions, adverse effects, and use in special situations-part 1: First-line drugs. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36:626-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Update on diagnosis and treatment of immune thrombocytopenia. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14:553-68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wet purpura: A sinister sign in thrombocytopenia. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017 bcr2017222008

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Re: Risk factors and predictors of treatment responses and complications in immune thrombocytopenia. Ann Hematol. 2022;101:447-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Rifampicin-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Br Med J. 1970;3:24-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug-induced thrombocytopenia: Pathogenesis, evaluation, and management. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;2009:153-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Do not miss rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenic purpura. Case Rep. 2012;2012 bcr1220115282

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Antibodies against rifampin in patients with tuberculosis after discontinuation of daily treatment. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:1189-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safety and efficacy of azathioprine in immune thrombocytopenia. Am J Blood Res. 2021;11:217-26.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Potentially serious side effects of high-dose twice-weekly rifampicin. Br Med J. 1971;3:343-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:240.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Glycoprotein Ib/IX complex is the target in rifampicin‐induced immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:907-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug-induced thrombocytopenia: A systematic review of published case reports. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:886-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifampicin-induced thrombocytopenia: A rare complication. J Assoc Chest Physicians. 2019;7:38-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Real-world experience of rituximab in immune thrombocytopenia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2021;37:404-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]