Translate this page into:

NAMS task force report on mental stress

Corresponding author: Dr. Rajesh Sagar, Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. rsagar29@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sagar R, Chatterjee K, Thareja S, Timothy A, Yadav AS, Yadav P, et al. NAMS task force report on mental stress. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci (India) 2025;61:66-97. doi: 10.25259/ANAMS_TFR_10_2024

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization has defined stress as “A state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation”.1 The “difficult situation” or the stressor can range from normal day-to-day stressors like missing a bus, or it can be a challenging situation like a job interview, conflict with friends or family, or an event that affects a large number of people at a time like natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and major economic crises.

Stress affects both the mind and the body. The effect of the stressor on the physical and mental health of an individual can be either positive or negative depending on the interplay of multiple factors—the severity of the stressor, the controllability of the stressor by the person experiencing the stressor, duration of stressors, and the availability of resources to manage the stressors. The resources here include psychological resources (coping skills, personality traits, attitude, values, etc.), social and financial resources, as well as physical health-related factors, that one can use in responding to the stressor.

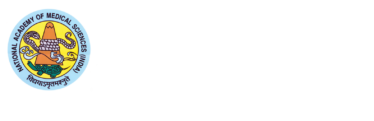

While the term “stress” connoting difficulty or challenge made an appearance in the literature as early as the 14th century, it was during World War II that a heightened curiosity emerged surrounding emotional breakdowns triggered by the pressures of combat. It was found that numerous circumstances in everyday life—such as the process of maturing, marriage, or experiencing illness—could evoke effects akin to those seen in combat situations. This resulted in a growing inclination to view stress as a significant contributor to human dysfunction and distress.2 However, further studies have expanded the concept further to include not only distress but also eustress (Figure 1).

- Types of stress.

Eustress is a type of stress where homeostasis is mildly challenged by moderate levels of positive stressors that may lead to mild stress response. Sustress is a type of stress where homeostasis is either not challenged or inadequately challenged, eventually affecting the homeostasis negatively and worsening health. Distress is a type of stress where homeostasis is strongly challenged and worsens health.3

Since the concept of stress is broad and it is the distress that leads to more negative effects or damage to an individual, it was mutually decided by the members of the task force that the current article will focus only on the “Distress.” Hence, in this article, hereafter, the term “stress” refers to “distress” unless specified otherwise.

Models of stress

Stimulus-based models

Stimulus-based models interpret stress as a stimulus, a life event that evokes physiological and psychological responses, which may increase an individual’s vulnerability to developing health issues and dysfunction at various levels. Using this conceptual framework, Holmes and Rahe developed a Stress scale that lists 43 life events, both positive and negative, that can be considered stressful.4

Response-based models

The response-based model developed by Selye conceptualized stress as a “response”.5 Selye proposed the “General Adaptation Syndrome,” which suggests that stress triggers a physiological response involving three stages: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion. During the alarm stage, the body reacts with the fight-or-flight response, preparing to confront the stressor. If the stress persists, the body enters the resistance stage, attempting to cope with the ongoing challenge. However, if the stress becomes chronic and overwhelming, the body enters the exhaustion stage, leading to a breakdown of physiological systems and increased vulnerability to illnesses.

Transactional model

Another prominent model of stress is the “Transactional Model,” proposed by Richard Lazarus and Susan Folkman in the 1980s. This model emphasizes the dynamic nature of stress, suggesting that it emerges from the transactional process between an individual and their environment. Stress is perceived through an individual’s assessment of a situation’s potential harm and their ability to cope with it. This appraisal leads to either adaptive or maladaptive responses, influencing the overall impact of stress on well-being.6

While Lazarus acknowledged specific environmental conditions as stressors, he also highlighted the variations in individuals and groups in perceiving and responding to these stressors due to differences in sensitivity and vulnerability of the cognitive processes that arise between a stimulus and the corresponding response.

Allostatic load model

In recent years, the “Allostatic Load Model” has gained traction considering the cumulative physiological toll of chronic stress. This model focuses on the body’s attempts to maintain stability through physiological adaptations, which can become maladaptive when stressors are prolonged or intense. Over time, this can result in “allostatic load,” where the wear and tear on bodily systems contribute to various health problems. This model underscores the importance of early intervention and stress management to prevent long-term health consequences.7

Importance of stress

Stress is a universal phenomenon. The global prevalence of stress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic has been observed to be around 36.5%, and that of psychological distress is around 50.0%.8 The studies available before the pandemic have shown that the prevalence of psychological distress in the general population varied from 5 to 27%, depending on the screening tool and the methodology used. The prevalence in certain special populations such as migrants, workers facing stressful work situations, and elderly who have faced neglect or abuse is even higher.9

The stressors can occur from various sources, such as environmental stressors, physical pain, circadian disruptions, and substance consumption. Also, stressors can differ significantly in their strength, ranging from mild to severe, and in terms of their duration or timing, spanning acute, chronic, or intermittent periods. It is also essential to acknowledge that not only do stressors come in a wide range, but an individual’s response to a stressor can also vary significantly based on various factors such as sociodemographic factors, personality factors, the presence of social support, and prevailing social norms.

Stress has been identified as a factor that can heighten the likelihood of various physical illnesses, and it may also worsen preexisting physical conditions. Similarly, stress can elevate the risk of mental illnesses, particularly depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Moreover, it has the potential to intensify the severity of preexisting mental health conditions, contributing to a decline in the overall quality of life and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.

Given that mental stress is a widespread phenomenon affecting individuals across diverse backgrounds, it becomes imperative to comprehend the current situation of mental stress in our country. This article aims to provide an overview of the existing mental stress scenario, delineate the consequences of mental stress, highlight gaps in current policies and programs, and propose recommendations for enhancing the current situation.

BACKGROUND

Medical professionals can play an important role in identifying and managing mental stress in the general population, which in turn can help in the prevention of mental illness and mental health promotion. The National Academy of Medical Sciences (NAMS), India, along with the Armed Forces Medical Services (AFMS) have constituted a Joint Task Force on Mental Stress to develop a white paper that can be submitted to the Government of India to develop guidelines and to improve the interventions addressing the problems of Mental Stress in Indian population. In pursuance of the meeting of NAMS held on August 08, 2023, and the constitution of a Task Force on Mental Stress to develop a white paper to be submitted to the Government of India for improving the health intervention activities in the area of Mental Stress, the objectives of the task force were laid out.

This white paper document discusses the extent of mental stress-related problems in India, offering a roadmap for policymakers to address these more effectively with the help of evidence-based interventions.

TERMS OF REFERENCE (TORS) FOR THE TASK FORCE

The main objectives of the Task Force were as follows:

To identify the current status of mental stress

Identify the deficiencies which need to be addressed.

To recommend measures for the management of mental stress

METHODOLOGY

The task force reviewed the current reports and data on mental stress in India. It then developed a consensus on the key observations and recommendations by considering the healthcare services and the varied social-cultural-economic contexts across the Indian landscape. The initial working draft was circulated among the task force members, and comments were sought. The working draft was modified based on their suggestions. Subsequently, online meetings were held in which the experts deliberated on the various aspects of the document. Further modifications were made to the document based on the inputs received from experts.

OBSERVATION AND CRITICAL REVIEW

Current situation in the country

Since the concept of mental stress has varied across the literature, the scales used to screen for mental stress, and the methodology used in the studies have also varied. As a result, the prevalence of psychological stress or distress in the general population has also varied across studies from 5 to 27%.9 In India, there has been no nationally representative study to find the prevalence of psychological stress in the general population, even though there are many studies that have tried to assess the prevalence of mental illness in the country.

In India, the total disease burden due to mental disorders has almost doubled since 1990.10 The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) conducted in 2016 across 12 states found that the weighted prevalence for any mental illness in the lifetime was 13.7% and that for current mental illness was 10.6%. Apart from substance use disorders, mood disorders, and neurotic or stress-related disorders were found to be the most common mental disorders [Table 1].11 The prevalence of mental health disorders according to global burden of disease study has been mentioned in Annexure.

| Mental illness | Prevalence (NMHS, 2016) |

|---|---|

| Mental and behavioral problems due to psychoactive substance use | 22.4% |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | Lifetime prevalence - 1.4%; |

| Current prevalence - 0.4% | |

| Mood disorders | Lifetime prevalence - 5.6% |

| Current prevalence - 2.8% | |

| Neurotic and stress-related disorders | Lifetime prevalence - 3.7% |

| Current prevalence - 3.5% |

NMHS: National Mental Health Survey

Most studies in India that have tried to assess the prevalence of mental stress or psychological distress have focused on specific populations, such as adolescents and the elderly. There have been very few studies that have focused on the general population.

Some of the studies conducted in the general population have been listed below:

A cross-sectional, community-based study conducted among 943 participants in a rural community among the adult population in India found the prevalence of psychological distress to be around 42.4 per thousand, around 0.04%. Being illiterate and being separated or divorced was found to be associated with psychological distress.12

A meta-analysis of 21 cross-sectional studies during the COVID-19 pandemic in India found the overall prevalence of psychological distress among the general population was around 33%. There was significant heterogeneity across studies, with prevalence ranging from 2.4 to 84% depending on the scales and the methodology used.13

A cross-sectional study to assess the psychological distress among healthcare workers in India during the COVID-19 pandemic found the prevalence to be around 52.9%, with the risk being significantly associated with longer hours of work, income, screening of patients, or contact tracing. Also, high emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were found to be associated with higher psychological distress.14

Studies on the prevalence of psychological distress in other countries

As the majority of studies on psychological distress among the general population are from countries outside India, the current study also reviewed these studies to understand the prevalence and various factors associated with psychological distress.

The prevalence of psychological distress has varied across studies and countries from 5 to 27% in the general population, depending on the tools and the methodology used. However, the prevalence among certain populations, such as migrants and workers facing stressful work situations, can be higher.9

A study that analyzed data from 202,922 participants of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance system in the USA found the prevalence of serious psychological distress to be around 2.1% in the total population.15 Multiple studies that analyzed the data from the 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, a nationwide survey conducted in the USA, found that psychological distress (Assessed using the Kessler 6 Questionnaire) was associated with abnormal body mass index (BMI, either underweight or obese),16 urban residence,17 and smoking status (current and former smokers).18

Another study from Canada which analyzed data from 11,058 participants from the first 12 years of the National Population Health Survey found that nearly 11% of participants experienced at least one episode of psychological stress over 12 years.19

In a longitudinal study involving over 400 adults and their children in the USA, it was observed that the occurrence of negative life events and the adoption of avoidance coping strategies were correlated with an increased likelihood of experiencing psychological distress. Similarly, in children, a higher risk of psychological distress was linked to parental emotional and physical distress. At the same time, an easygoing disposition, family support, and self-confidence were associated with a lower risk of psychological distress.20

A study conducted in Pakistan on 1000 adults aged between 18 and 75 years found the prevalence of psychological distress to be around 41% in women and 19% in men (Scale used: Self-reporting questionnaire [SRQ]). The study also found that lower educational status, lower income, and recent hospitalization (in the past 12 months) were associated with higher rates of psychological distress.21

Factors affecting mental stress

A large number of factors have been proposed to moderate stress. A stressor can act as a catalyst, presenting a challenge or predicament that compels an individual into action. Whether a situation is perceived as stress-inducing or not hinges on several factors and individual variations. Stressors can be categorized into two types: major life stressors and daily hassles. The former type is associated with alterations or disruptions related to key aspects of people’s lives, for example, shifting to a new city for a job. On the other hand, the latter involve minor, day-to-day vexations or frustrations, such as waiting in line or dealing with challenging individuals. Despite their seemingly small nature, daily provocations can also result in considerable stress, and the cumulative effect of numerous such issues can be as impactful as significant life changes.22

Another category of stressors that are of importance are those that are chronic. Wheaton et al.,23 (1997) has given seven types of events or situations that may be understood as chronic stressors:

Threat of regular physical abuse or staying in high-crime areas

Expectations that cannot be met with current resources

Structural constraints, such as lack of higher education facilities near home

Discrimination in the job

Instability in life arrangements, conflicts of responsibilities across roles, for example, in the case of working women

Uncertainty

Ongoing conflicts in personal, social, environmental, or political scenarios.23

It is well-known that there is individual variability in a person’s response to stressful situations. While some individuals manage even the most extreme situations, some may get distressed even with minimal demands. Hence, the role of individual factors is paramount in determining whether a person will develop psychological stress. At the same time, there are certain situations or stressors like disasters, war, and so on, which can cause psychological distress in many individuals. The ability of an individual to come out of these stressful situations will depend on not only the individual factors but also the availability of social support and other resources such as shelter, clothes, food, and security. Hence, mental stress can occur either due to the nature of the stressor or, due to individual vulnerability or a combination of both. Hence, while some individuals tend to show stressor responses associated with active coping, others tend to show stressor responses associated with aversive vigilance (Llabre, 1998).24

While several factors can increase or decrease psychological stress, we have enlisted some of the most important and major factors associated with psychological stress based on the literature.

Demographic factors associated with higher risk of mental stress

Age: Extremes of age

Gender: Female gender

Education status: Lower education

Marital status: Unmarried or Single status

Residence: Urban locality

Economic Status: Lower income

Work: Unemployment

Physical health-related factors associated with higher risk of mental stress

Presence of physical disability

Recent hospitalization

Chronic physical illness

Abnormal BMI (Not being physically fit)

Less exercise

History of physical illness

Social factors associated with a higher risk of mental stress

Uncertainty about the current situation (e.g., refugees)

Uncertainty about future (e.g., refugees)

Minority status (e.g., ethnic minority, sexual minority, etc.)

Poor social support

Societal norms – Can act as both protective and risk factors at times

Environmental factors

-

Daily life situations

For example, being late for work, missing the bus to work, and so on can increase the risk

-

Positive uplifts in daily life

For example, getting appreciated at work and so on can decrease the risk

-

Major life events:

For example, marriage, divorce, birth of a child, death of a loved one, and so on, can increase or decrease the risk

-

Exposure to trauma or adverse life experiences can increase the risk

Exposure to childhood sexual abuse

Exposure to bullying or rejection in the form of being ignored, cursed, or assaulted

Exposure to parental emotional distress or parental physical distress

Exposure to physical abuse, including intimate violence

Exposure to substance use by a family member

Being a caregiver of a person with a mental illness

Being a caregiver to a person exposed to disaster

-

Acculturation stress

Migrating to a new cultural environment, language barriers, and so on can increase the risk

-

Workplace factors:

-

Risk factors at workplace:

Dissatisfaction with job

Family–work conflict

Long working hours

Nontraditional gender roles at work

Loneliness

-

-

Protective factors at the workplace:

Having active participation in the job

Ability to maintain work and family roles successfully

Perceived control in the job

Higher academic stress can increase the risk for students

Psychological factors

-

Temperament:

Negative affectivity increases the risk

Easy-going temperament lowers the risk

Lower psychological flexibility increases the risk

Personality factors:

-

Risk factors:

Higher neuroticism

Higher conscientiousness

-

Protective factors:

Openness to experience

Extraversion

Agreeableness

-

Coping skills:

-

Risk factors:

Emotion-focused coping

Avoidance or escape coping

-

Protective factors:

Problem-focused coping

Gratitude, optimism, and self-compassion have lower risk

The presence of mental illness symptoms has a higher risk

History of mental illness has a higher risk

-

Consequences of Mental Stress

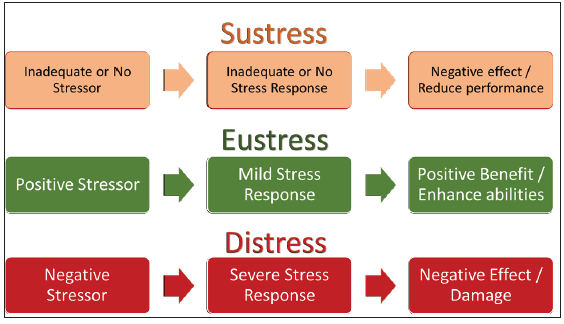

Some amount of stress is necessary to propel an individual to act or deal with the situation. The Yerkes–Dodson law, proposed in 1908, elucidated that the performance increased with stress or arousal only to some extent, beyond which it started declining. It further stressed that insufficient stress would lead to disinterest or boredom and decreased performance [Figure 2].

- Yerkes–Dodson law.

However, extreme or prolonged stress can have physiological, psychological, and social ramifications. A systematic review comprising 47 studies revealed that elevated stress reactivity in both the situationally accessible memory (SAM) system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis was predictive of a heightened risk of cardiovascular diseases. Conversely, blunted stress reactivity was associated with an increased likelihood of future obesity, depression, anxiety, higher illness frequency, pains or aches, diminished cognitive ability, poor self-reported health, and disability.25

Physiological effects: The hypothalamus is affected in the same manner by our internal anger, as well as our guilt and resentment toward other people and ourselves. But, we trap this tension inside where its consequences compound rather than letting it go. Research indicates that nearly every bodily system can be impacted by chronic stress. When chronic stress is not relieved, it hampers the immune system, leading to illnesses. Fortunately, in typical situations, 3 minutes after the cessation of a threatening scenario and the elimination of real or perceived danger, the fight-or-flight response diminishes. Consequently, the body relaxes and reverts to its usual state. During this period, several physiological functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, muscle tension, digestion, metabolism, and the immune system normalize. If stress persists beyond the initial fight-or-flight reaction, the body’s response progresses to a second stage.

Effect on physical health: Psychological distress is well known to lead to an increase in the risk of physical illness, as well as worsen the course of physical illness.

Stress and immune system: The harmful effects of chronic stress lead to dysfunction of the HPA axis, which in turn leads to impaired immune system, reduction in activity of the T-lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells, and predisposition to malignancies.

Stress and cardiovascular system: Stress, both acute and chronic, has a deleterious effect on the cardiovascular system, as it causes chronic activation of the autonomic nervous system, leading to vasoconstriction, atherogenesis, increase in blood pressure, and so on. A systematic review of 24 prospective studies found that psychological distress was associated with a significantly increased risk of recurrent cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease.26

Stress and Gastrointestinal (GI) system: Stress affects not only appetite but also the absorption process, intestinal permeability, mucus and stomach acid secretion, function of ion channels, and GI inflammation. Stress can also alter the functional physiology of the intestine. Many inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and other ulcerative-based diseases of the GI tract, are associated with stress. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is considered a functional disorder related to stress.

Diabetes: Higher levels of chronic psychological stress and, more importantly, a decreased stress-coping ability measured as a sense of coherence (SOC)27 were associated with a greater risk of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) among Indians. A dysregulated HPA axis28 driven primarily by arginine–vasopressin (AVP)29 was observed to be the possible link in this association. A significant association of psychological stress with oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in the context of T2DM was also documented.30 All these findings were novel and hitherto unreported in Indians.

Mortality: An individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies among 68,222 individuals found a higher risk of all-cause mortality, deaths due to cardiovascular diseases and external causes.31

Effects on mental health: Stressful living circumstances increase the risk of mental illnesses, including depression and anxiety. Psychological stress has been associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders. Apart from psychiatric disorders, psychological distress is also associated with an increased risk of sleep disorders, dementia, memory disturbances, eating problems, and so on.

Memory disturbances: Chronic stress leads to impairment of the HPA axis, leading to changes in the hippocampus that consist of a high density of cortisol receptors. This leads to impairment in memory and learning.

Depression: Depression is one of the most common mental health issues, with a prevalence rate of 5%.32 The relationship between stress and depression has long been studied. Initially believed to be unidirectional, recent studies on the stress–diathesis model indicated a bidirectional relationship. Recently, the focus has been shifted to the awareness that stressors during early developmental years, such as loss of parent(s) and bullying, as well as enduring or chronic stress, such as marital or occupational circumstances, are strong indicators of depression.33,34 A recent key pursuit has been the investigation of accumulated stress (measured through allostatic load) and its influence on depression and other psychological issues. Biological components such as increased cortisol levels and dysregulation in the HPA axis have been implicated in both stress as well as depression.35 In comparison to age- and gender-matched controls, a study of 13,006 Danish patients with initial psychiatric admissions diagnosed with depression showed higher instances of recent divorces, unemployment, and relative suicides. A serious medical diagnosis is often considered a severe life stressor and is frequently linked with elevated rates of depression. For instance, a review indicated that approximately 24% of individuals diagnosed with cancer experienced major depression.36 Future research should enhance the specific factors influencing the relationship between stress and depression by employing reliable and consistent methodologies.

Anxiety and stress-related disorders: Anxiety serves as the physiological and psychological indicator that the body’s stress response has been activated. Unmitigated stress has been shown to precipitate the development of anxiety disorders as well as stress-related disorders such as acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD). Roughly 4.05% of the worldwide population, corresponding to around 301 million individuals, suffers from any anxiety disorder.37 According to the NMHS conducted in India, the prevalence of any anxiety disorder was found to be 3.6%, and that of PTSD was found to be about 0.2%.11 The prevalence of ASD is estimated between 5 and 20% following a traumatic or stressful event. Stress-induced changes in brain regions, such as shrinkage in hippocampal volume have been implicated in ASD as well as PTSD.

Sleep disorders: Sleep disorders have been reported in 25–30% globally.38 The relationship between stress and sleep problems is a commonplace phenomenon. Recent research has shed light on the presence of a sleep-specific aspect of stress reactivity, and the phenomenon has been termed “Sleep reactivity.” Sleep reactivity has been understood as the individual variation in sleep disturbances in response to exposure to stress. Sleep disorders have been implicated in various physical and mental health issues, including cardiovascular diseases and depression. A recent meta-analysis indicated a moderate association between sleep quality, insomnia, and stress in undergraduate students.39 On the other hand, sleep disorders also affect one’s capacity to tolerate stress as well as stress reactions.

Eating habits: Eating has frequently been associated with stress. Studies examining the relationship between stress and eating habits have predominantly evaluated stress by several methods, such as tallying life events, evaluating ongoing stress factors, or concentrating on daily hassles. It has been reported that high cortisol levels are associated with increased consumption of calories. Moreover, when stressed, people decrease their consumption of healthy foods. Evidence also points toward an association between stress and eating disorders, especially binge eating disorder. Research has been conducted primarily on the adult population to understand the relationship between stress and eating habits. Only a few studies have been conducted on young children and adolescents, which found a positive correlation. Potential mechanisms that explain the association between stress and eating habits include mood, negative automatic thoughts, coping, and hormonal changes.40

Substance use and substance use disorders: Stress has been implicated in initiation as well as maintenance of substance use disorders. However, most studies were cross-sectional and did not allow us to infer cause-effect relationships. Longitudinal studies have reported that other factors such as poor family support, poor coping styles, stressful life events, migration, and gender also mediated the relationship between the two.41

Studies have found that populations that live in highly stressful environments tend to smoke heavily and experience higher mortality from lung cancers and cardiopulmonary diseases (COPD). Chronic, stressful conditions have also been linked to higher consumption of alcohol. Alcohol may also be used as self-medication for stress-related disorders. The correlation between acute and chronic stress and the desire to use addictive drugs is well documented in the literature. Many of the major theories of addiction have identified stress as an important cause of addiction processes. These range from psychological models of addiction that view drug use and abuse as a coping strategy to deal with stress and reduce tension to self-medicate and decrease withdrawal-related distress.

Numerous population-based and clinical investigations have found strong evidence for the link between psychosocial adversity, negative affect, chronic distress, and predisposition to addiction. Negative life experiences, including parent death, parental conflict and divorce, limited parental support, physical and emotional abuse and neglect, social isolation, and deviant affiliations, have all been linked to an increased likelihood of drug dependence. Additionally, there is overwhelming evidence linking childhood maltreatment, misuse of drugs, and abuse of sexual and physical abuse. After taking into consideration a variety of control factors, including race or ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic level, past drug misuse, the incidence of mental illnesses, family history of substance use, behavioral and conduct issues, and lifetime exposure to stressors, researchers have recently looked at the effect of cumulative adversity on addiction vulnerability. Even after considering control variables, the results showed that the total number of stressful episodes was a dose-dependent significant predictor of alcohol and drug dependency. Addiction susceptibility was strongly and independently impacted by both proximal and distal events. Even though there are many effective behavioral and pharmaceutical therapies for the treatment of addiction, recurrence rates of addiction are still very high. Exposure to stress can reinstate drug-seeking behavior in animals and increase relapse susceptibility in addicted individuals.

Stress and psychosomatic disorders: Many studies have indicated the strong link between stressful life events and IBS. In general, psychosocial factors are followed by the onset or exacerbation of GI symptoms (Lee OY, 2006).42 IBS is a functional disorder with an etiology that has been linked to both psychological stress and infection. It is characterized by an overactivation of the HPA axis and a proinflammatory cytokine increase. (Dinan TG et al., 2006).43 Acute mental stress has a significant effect on the coronary artery blood flow that may be significant in patients with preexisting coronary disease.

Mental stress induces arterial endothelial dysfunction, with impaired vasodilatation and paradoxical vasoconstriction.

Special Populations

Stress can be triggered in children and adolescents when they experience something new or unexpected. While work-related stress is common among adults, most children and adolescents experience stress when they cannot cope with threatening, difficult, or painful situations. It is important to remember that children are like “sponges”; absorbing what is going on around them, noticing the stress of their parents, and reacting to that emotional state.

Children do not always experience stress the way adults do. Specifically, the younger children do not always understand what is truly happening because of their age and level of development. To them, a new or different situation feels different, uncomfortable, unpredictable, and even scary. Also, they may not always have the emotional intelligence or vocabulary to express themselves. On the other hand, older children and adolescents experiencing stress may refrain from discussing their worries with peers, parents, and teachers as they perceive that acceptance of stress is a sign of psychological vulnerability, which usually is not consonant with their evolving autonomy and self-esteem.

For young children, tensions at home, such as domestic abuse, separation of parents, or the death of a loved one, are common causes of stress. School is another common reason; making new friends or taking exams can make children feel overwhelmed. As children grow older, their sources of stress can increase as they experience bigger life changes, such as new groups of friends, more schoolwork, and greater access to social media and news around the world. Many teens are stressed by social issues such as climate change and discrimination.

The common causes of stress in children and adolescents include the following:

Negative thoughts or feelings about themselves

Changes in their bodies, like the beginning of puberty

The demands of school, like exams and more homework, as they get older

Problems with friends at school and socializing

Changes like moving homes, changing schools, or separation of parents

Chronic illness, financial problems in the family, or the death of a loved one

Unsafe environments at home or in the neighborhood

Specific factors contributing to mental stress in children

Family: Both children and adolescents reported severe illness, sickness, and death of a family member as significant stressors. However, children are more likely to identify such events as significant problems than adolescents. Interpersonal conflicts between parents and separation or divorce are other major contributory factors for stress in the younger population. Sibling rivalry, arising partly due to perceived differential treatment by parents, may not be limited to childhood and can be present in adolescents too, and can cause stress. The family dynamics involving the structural and systemic aspects, the roles and responsibilities, and expectations and accommodation put an additional burden on the developmental trajectory of an adolescent. Stressors arising from parent-child interactions are reported with increased frequency among adolescents.44 The most common sources of parent-adolescent conflicts include issues related to adolescents’ autonomy and academic performance.

Peer group: The most commonly reported stress in peer group interaction is the phenomenon of peer rejection.44 For children and adolescents, peer rejection may occur through exclusion by a peer group or bullying. As approval of peers is intertwined with the concept of self-image, especially among adolescents, such rejections may act as an anchor for negative thoughts about self. For adolescents, peer rejection can also occur in the context of romantic relationships.45 Stressors associated with navigating relationships, particularly at the beginning and ending phases, are also reported by adolescents.46

School: School serves as an evaluative playground in both the cognitive domain and the socio-emotional field. Childhood encompasses transitions related to school, including first experiences with attending school away from parental and familial figures and salient transitions to middle and high school. The school itself can become a stressful place for the youth in case of barriers to smooth transitions, often manifesting as avoidance of school. School refusal behavior is a common problem across all ages, and even though the function precipitating and maintaining may be varied, it causes significant distress to the child-parent dyad.

Academics: Academic stressors commonly affect children and adolescents.47 In Indian settings, where the parameters of success are measured in terms of grades or marks, a child is always under constant performance stress to meet the expectations of self and significant others, including parents and teachers. Adolescents report academic stressors related to challenging coursework, which may not agree with their interests and aptitudes.

Various studies carried out after the year 2000 revealed that the prevalence of stress among Indian adolescents varied between 13% and 45%.48 A study on high school students49 revealed that nearly two-thirds (63.5%) of the Indian students reported of stress due to academic pressure.

In a cross-sectional survey of 632 Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) students during the COVID-19 lockdown, 6.48% and 0.92% experienced severe and extreme levels of anxiety, respectively. Females were more vulnerable as compared to males, and the maximum level of anxiety was found in MBBS first-year students, that is, late teens.50 Another study conducted on 612 MBBS students from Karnataka reported that the most frequent stressors included the vast academic curriculum, high parental expectations, adjusting to the new environment, moving away from home and staying in the hostel, and adjusting to new roommates. Eating was observed to be the most commonly employed coping mechanism.51

A cross-sectional study of 52 college students in New Delhi found high levels of academic stress but low levels of social and psychological stress. No association between stress and age was found. Stressors usually include a new environment, lack of structure in curriculum, high need for achievement, balancing newly found freedom and studies, peer pressures, and intimate relationships.52

Gender: There is a long history of valuing boys above girls, and therefore, female gender experiences overt and/or covert discrimination. Further, girls are prone to be at higher risk for specific stressful life experiences like sexual harassment and sexual abuse. Girls have been valued based on their physical appearance, and they continue to report greater stressors and pressures associated with meeting societal expectations for female beauty. Girls place greater stock in interpersonal relationships and are more emotionally intimate in relationships than boys. As a result, they are also more likely to experience more interpersonal burdens and stressors experienced by others in their social networks.53 Although both boys and girls have the same level of worry regarding academics and economics, girls are much more vulnerable to increased stress when it comes to issues related to future events, classmates, and personal health. Adolescent girls are found to perceive negative interpersonal events as more stressful than boys. Studies further revealed that adolescent girls experience more stress than boys.54 Women with multiple roles to play may have an increased level of stress. A study examined the relationship between perceived stress and psychological health among working women versus housewives in Jammu Kashmir (n = 150). A significant difference was seen in both groups in terms of perceived stress, which was found to be higher in the former, probably due to multiple role demands. A negative association was seen between perceived stress and psychological well-being in both groups.55

There is also evidence that in certain contexts, some forms of stress may be more commonly experienced by boys. A study conducted by Carlson and Grant56 on stressors affecting low-income urban adolescents found that boys in their study sample, especially those who were in gangs, reported more stress than girls, including exposure to violence and sexual stressors.57 Alarmingly, there has been an increase in the number of deaths due to suicide in males, and the common stressors or risk factors are young age (18–29 years), unemployment, being a daily wage earner, low education (between 9 and 12), which could be leading to few job opportunities or financial and family issues.57

Bias and discrimination: Children and adolescents who differ from the majority based on ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, or disability status are more likely to experience stressors related to prejudice and discrimination. Similarly, discrimination based on language differences has been documented.58 Further, children whose primary language differs from the dominant may also experience academic and social stressors related to language.

Acculturation: International studies report that children and adolescents whose families have immigrated from other countries may experience various acculturation stressors.59 The stressors may range from stressful interactions with parents who may not wish to acculturate as quickly (or at all) to their children to experiencing heightened tension between peer and cultural groups. Since India is a country of cultural diversity, the construct of such stressors related to cultural differences arising due to regional differences can be extrapolated within the national boundaries as there is a rapid movement of people from one state to another in search of better employment opportunities.

Poverty: When poverty is experienced regularly, it has a significant impact on a variety of outcomes in children and adolescents. It affects both proximal and distal stressor variables. At the family level, it is linked to an increased risk of marital conflicts, separation, divorce, and negative parent-child interactions. Furthermore, children and adolescents living in urban areas with persistent poverty are more likely to be victims of community violence and crime. Similarly, children who live in poverty are more likely to have limited resources at school, poor school functioning, and/or problematic school and peer climates.60

Psychosocial adversity: Apart from poverty, some of the other factors responsible for psychosocial adversity include exposure to physical and sexual abuse, neglect, physical illness, and natural disasters. Also, cyberbullying, dating violence, intimate partner violence, and drug abuse can result in an environment of stress for older adolescents. Such stressors may be less common but are more severe and are associated with higher levels of psychopathology.

Over the past two centuries, there has been a consistent upward trend in human life expectancy, which has contributed to the worldwide phenomenon of population aging.61 This natural process of growing older is accompanied by several challenges, including various forms of loss, such as financial security, psychosocial connections, and personal identity, as well as diminishing health, independence, and cognitive functioning. Moreover, loss of spouse or friends, caregiving responsibilities, retirement, an “empty nest” and elderly abuse can further exacerbate the issues.

While it is widely acknowledged that stress influences the aging process, there is no unanimous agreement on the specific dynamics of this relationship or the mechanisms at play. The interaction between stress and aging is contingent upon various factors like the type of stress, its duration, and intensity. Over the years, studies have tried to answer questions related to whether age affects resilience to deal with stress, whether stress accelerates aging, and regarding individual differences in coping.62

Research has explored the impact of persistent stress on the mental well-being of older individuals through various studies involving different populations. These populations include individuals dealing with chronic medical conditions, those who have experienced the loss of a spouse, and caregivers tending to family members with dementia.

Risk factors specific to the geriatric population:

Elderly abuse: A cross-sectional study conducted among 9589 older adults aged 60 years and above in India across seven states, namely Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Maharashtra, found the prevalence of psychological distress to be around 40.6%. The study also found that elderly abuse was found to be associated with a higher risk of psychological distress.63

Financial dependence: A cross-sectional study in Dharan, Nepal reported that the majority of elderly people experienced some kind of stress, with 9% reporting severe stress. Increased stress was associated with advanced age, lower educational levels, and high financial dependence.64 Similar findings have been reported in studies conducted in India.65 Studies have also shown evidence of a connection between long-term financial stress and health in the elderly; more specifically, studies showed evidence that perceived long-term financial pressures throughout a person’s life were strongly correlated with certain health-related outcomes in later life, such as self-rated health status, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment.

Social and familial support: In another study from India on elderly living in old-age homes, it was found that as high as 30% of individuals reported severe stress, highlighting the lack of social and familial support for the high indices of stress in this population.66 These investigations have helped establish connections between stress, coping mechanisms, and the development of mental health disorders in older adults.67

Functional limitations: A study conducted in Australia among 626 Australians aged 60 years and above found that older age, higher functional limitations, lower social support, and more time spent sleeping were found to be associated with a higher risk of psychological distress.68

Consequences of mental stress specific to elderly: Chronic stress is associated with inflammation, which has been implicated in various mental and neurological issues in the elderly, such as insomnia, late-life depression, anxiety, and dementia, specifically Alzheimer’s. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 20% of people above 60 years of age suffer from a mental or neurological disorder, accounting for 17.4% of Years Lived with Disability (YLD).69 The most common mental illness seen in the elderly is depression, followed by anxiety disorders, substance use, and death due to suicide.

Various indicators of stress in the geriatric population are evident in the form of sleep disturbances, mood instability and irritability, changes in appetite, somatic complaints, withdrawal from others or clingy behavior, and difficulty making decisions.

Despite high rates of physical and psychological ramifications of stress in the elderly, this area has been consistently neglected, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Working population: The WHO defines workplace stress as the response individuals may have when confronted with job demands and pressures that do not align with their knowledge and abilities, posing a challenge to their coping abilities. It can stem from inadequate work organization (such as the design of jobs and work systems and their management), suboptimal work design (e.g., a lack of control over work processes), ineffective management, unsatisfactory working conditions, and insufficient support from colleagues and supervisors.

The workplace encompasses several elements that converge to shape the overall employee experience. These elements encompass physical aspects such as office infrastructure, layout, and ergonomic considerations, as well as cultural components, including communication norms, organizational support, trust levels, decentralization practices, employee engagement, and the established policies and procedures governing work processes. Furthermore, technological dimensions, including digitalization and the tools facilitating work activities, play a pivotal role in this comprehensive work environment.70

The presence of robust social support from colleagues and supervisors can alleviate the adverse effects of stress and enhance the overall well-being of employees. Additionally, research has demonstrated that fostering a positive social support network bolsters job satisfaction diminishes employees’ intentions to leave their positions, and promotes retention within the organization. A conducive work environment plays a pivotal role in elevating employee happiness, engagement, and productivity. Conversely, an unfavorable work environment can result in disengagement, diminished loyalty, and increased turnover rates among employees.71

The survey by the 7th Fold (2020) with 509 working people across metro cities and diverse sectors from India revealed that 36% of the employees suffered from one or the other type of mental health issues. The situation of mental health has been exacerbated due to the COVID-19 pandemic, making it a more serious concern. India ranks first among 18 nations in terms of stress, as per a survey conducted by Deloitte during the second wave of the epidemic. According to a recent PwC survey on employee financial wellness for 2021, 63% of workers have been under financial stress since the start of the COVID-19 epidemic. These studies suggest that workplace mental health requires immediate attention.

Employee well-being and organizational success are paramount concerns in human resource management. In today’s dynamic work landscape, addressing work-related stress, bolstering job satisfaction, and mitigating job insecurity have taken center stage.

The prevalence of work-related stress has made it an integral part of the modern workplace. Concurrently, the Indian workforce has experienced heightened levels of job insecurity. Various studies from India involving engineers and blue-collar workers have found that high job stress and levels of job satisfaction are negatively correlated, and the differences were stable across gender.72

Stress is common among mental health professionals and subsequent treatment-seeking is quite low, which affects not only their well-being but also their ability to provide services to others. A cross-sectional study conducted on mental health professionals working in a tertiary care neuropsychiatric center (n = 101) observed low work-life balance, higher perceived stress, higher levels of psychological distress, higher secondary trauma, and high levels of burnout. Increasing age, belonging to a department, staying with family, and better monthly income were found to be protective factors.73

Specific factors leading to stress among workers:

Discrimination at the workplace: According to a cross-sectional study, conducted in 2016, in 35 nations including India, almost two-third of employees Brouwers et al.74 (2016) who had experienced depression faced discrimination at work or while seeking new positions.

Sexual harassment and bullying: Another work-related stress that can occur in any business is sexual harassment and bullying. Both sexes may be impacted, although women and people at the bottom of the social order are frequently more vulnerable.

Family–Work balance: A study conducted on 34,468 Finnish people currently engaged in active work found that loneliness, job dissatisfaction, and family–work conflict were associated with a high risk of psychological distress, while having children being actively involved in work, successfully combining family and work roles, and presence of social support were associated with lower risk of psychological distress.75 A cross-sectional study of 217 teachers working in Kerala was conducted to understand the relationship between workplace factors and employee indifference and burnout. Results indicated a negative relationship between workplace factors and employee indifference, which increased with burnout.76

Consequences of stress at the workplace: A variety of physical ailments, including hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders, among others, can be exacerbated by poor mental health at work. According to recent research, employee productivity is influenced by their mental health and is correlated with their effectiveness. Consequently, it is critical to give priority to the employees’ mental health.

Other special populations:

Caregivers of individuals with mental illness: A cross-sectional study conducted among two groups of individuals (240 each) living with and without a person with mental illness, respectively, found the prevalence of psychological distress to be around 50% in those living with a mentally ill compared to those not living with a mentally ill.77 Very few Indian studies exist on the stress of parents with children having neurodevelopmental disorders despite it being consistently shown that this group reported higher stress as compared to other parents with typically developing children. One hundred thirty parents from Northern India of preschool children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders were assessed for their stress levels. It was found that parental stress was strongly associated with poor attention span and behavioral issues in the children.78

Females: A prospective cohort of 1500 females found neuroticism traits or antisocial behavior in adolescence and a history of psychiatric or physical illness. Divorce among parents has been found to have an increased risk of psychological distress among females in midlife.79

Refugees/migrants: A cross-sectional study conducted among 75 migratory construction workers in India found the prevalence of psychological distress to be around 64.0%, with females having more distress compared to males.80

A study conducted among 2639 adult refugees in Germany found that females of older age, those at risk of deportation, those in refugee housing facilities, and those not in private housing had a greater risk of psychological distress.81 Another study conducted among 1062 Russian-born immigrants to Israel found that compared to males, females had higher psychological distress. Factors such as family problems, inappropriate climate conditions, anxiety about the future, uncertainty in the current situation, and poor health were associated with this higher risk among females compared to males.82

Survivors of trauma/disaster: The average person experiences several traumatic incidents during their lifetime, particularly in developing nations like our own. Following life-threatening traumatic events, both acute stress response and PTSD are frequent. According to many studies,83 traumas and disasters are linked to PTSD, as well as concomitant depression, other anxiety disorders, cognitive impairment, and drug addiction. A study conducted among 527 trauma survivors found that the severity of PTSD symptoms was associated with younger age, ethnic minority status, unemployment, low income, unmarried status, and type of trauma, with assaultive trauma showing higher risk.84

Current Infrastructure, facilities, technologies, policies, programs, and so on in the country in the context of the problem/health issue

Current infrastructure and facilities

The government and other organizations have been providing community mental health services since the NMHP was established in 1981. The major aim of the NMHP is to deliver basic psychological health care at the grassroots level, as well as to ensure that services are available and accessible to the most vulnerable and underprivileged people. In India, government spending on mental health accounts for only 0.06% of the total health expenditure, which accounts for barely 4% of the national gross national product (GNP). In India, only 43 mental hospitals with 1.469/100,000 beds, 0.047/100,000 psychologists, and 0.301/100,000 psychiatrists exist. Qualified personnel are scarce. The availability of mental health nurses and social workers is 0.166/100,000 and 0.033/100,000, respectively. Mental health infrastructure is mostly restricted to huge, semi-permanent facilities which serve a small number of people. We are still in the early stages of completely allowing patients, families, and communities to fulfill the three goals of mental health, promotion, prevention, and treatment. The objectives of the District Mental Health Program (DMHP) as envisaged in the 12th 5-year plan were: To reduce mental illness-related distress, disability, and premature mortality, as well as to improve rehabilitation from a mental condition by assuring that psychiatric care is available and accessible to all, specifically the most marginalized and poor members of society. Other objectives were as follows: reduce stigmas, encourage community engagement, increase accessibility to preventative care for at-risk groups, safeguard persons with mental illness (PWMI) rights, and integrate mental health services with other programs such as rural and child health, motivate and empower employees, build administration, regulations, and accountability procedures to strengthen mental health service delivery infrastructure, develop awareness and information, and develop leadership, organizational, and accountability mechanisms. These goals are now being pursued through extending community services and improving community-based programs (satellite clinics, school counseling, workplace stress management, and suicide prevention), organizing community awareness camps with the assistance of local groups, increasing national involvement (through collaboration with conscience and caretaker organizations), forming public-private partnerships with designated financial cooperation, establishing a special 24-hour hotline number (e.g., to notify the public about urgent mental health services), assisting national and state mental health agencies in obtaining public funding, and so on. Hence, the concept of mental distress alleviation is being dealt with by not only psychiatrists but also a team of mental health professionals, including psychiatry social workers, mental health nurses, occupational therapists, psychologists, primary care physicians, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) workers, and volunteers from the community.

Application of technology in the alleviation of stress and mental health intervention: Technology creates opportunities for extending mental health services to remote areas. The use of technology in the field of mental health has given impetus at multiple levels.85 Information and communication technologies have yielded positive results in mitigating stress. Innovative technology-based interventions have helped to reach out to various age groups and to reduce stigma.86

Digital mental health interventions and technology interface: Digital mental health interventions (DMHI) have been categorized as “e-Health” through telemedicine or internet-based interventions and “m-Health” through mobile digital interventions such as smartphones or virtual and augmented reality applications.87,88

Internet-based Interventions (IBIs) can be effective in promoting healthy behaviors

Smartphone Apps: Efficacy was examined by the meta-analysis conducted by Linardon et al.89 (2019). It was noted that apps can be low-intensity, cost-effective, and easily accessible interventions for those unable to receive standard psychological treatment.

Virtual and Augmented Reality: Virtual reality is defined as “a collection of technologies that allow people to interact efficiently with 3D computerized databases in real-time using their natural senses and skills”.90 It has been helpful for relaxation as well as for the treatment of social phobia, etc.

Artificial Intelligence–based technologies (e.g., machine learning, deep learning) may bring phenomenal changes in understanding and preventing the occurrence of stress-related psychological disorders.91

With respect to mental health concerns and stress-related disorders, availability and access of trained human resources remain a challenge.92 Stigma of seeking help, availability of trained human resources, and geographic and economic challenges are some of the issues that supplement and advocate the implementation of DMHI.93 Systematic review and meta-analysis of DMHI to quantify the effectiveness of the interventions of DMHI revealed that they may be helpful if delivered under supervision and with active support.94 Some of the challenges are adaptations of the psychological interventions into digital formats.

The DMHI (e.g., Internet-based interventions, smartphone apps, mixed realities – virtual and augmented reality) provides an opportunity to improve accessibility to intervention in stress-related disorders. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses found that DMHI is effective in mild mental disorders; however, in-person professional consultation is associated with greater effectiveness and lower dropout than fully automatized or self-administered interventions.95

Tele-mental health: Tele-mental health involves technologies such as video-conferencing to deliver mental health services and education and to connect individuals and communities for healing and health. Tele-mental health is effective and increases access to care.96 Future directions suggest the need for more research on service models, specific disorders, the issues relevant to culture and language, and cost. Technology adoption for combating stress during the pandemic has opened many options for interventions. Information dissemination and mental health interventions attained momentum during this period. It involved the dissemination of authentic information through reliable resources of government-aided platforms. Technology-based solutions, information management, and the use of technologies97 were widely tried to alleviate distress. The stress mitigation initiatives through telework and online educational interventions are the key factors of an entirely new era of technology-based interventions in mental health. The primary advantage of these interventions is connectivity to remote locations where mental health interventions are not available for mitigating stress.

Tele-MANAS: The current National Tele-Mental Health Program (Tele Mental Health Assistance and Networking Across States [T-MANAS]) has been envisioned as the digital arm of DMHP as a further extension of the mental healthcare service in the country.

The Government of India introduced of the National Tele-Mental Health Program (T-MANAS) during the Union Budget 2022–23. The program was officially launched in October 2022. T-MANAS is a two-tier system comprising state T-MANAS cells, including trained counselors as first-line service providers at Tier 1 and mental health professionals at DMHP at Tier 2 to provide secondary-level specialist care. Referral services are also available for in-person consultations or audiovisual consultations through e-Sanjeevani, which is the national telemedicine initiative under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). The inclusion of tele-mental health services as a part of the mental healthcare deliverables is an expansion of digital mental health in the country.98 Following are the objectives of Tele-MANAS:

To enhance health service capacity to deliver accessible and timely mental healthcare through a tele-mental health network support system.

To ensure a continuum of services in the community, including tele-mental health counseling.

To facilitate timely referral for specialist care and follow-up as appropriate.

To enhance mental healthcare capacity and networking at primary healthcare or health and wellness centers/district/state/apex institution levels.

The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment launched a helpline to offer mental health rehabilitation services with the objective of early screening, first aid, psychological support, distress management, promoting positive behaviors, and so on. The helpline is available in 13 languages and has 660 clinical or rehabilitation psychologists and 668 psychiatrists as volunteers. It is being coordinated by the National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Multiple Disabilities (NIEPMD), Chennai (Tamil Nadu) and the National Institute. It aims to cater to people in distress, people impacted by pandemic-induced psychological issues, and Mental Health Emergencies.

Mental well-being Apps: There are many apps available commercially but lack scientific validity. Under the mental health augmentation strategies, Sleep App, Mindfulness App, and Relaxation Apps are available. There is a strong need to regulate the practice of referring these apps for practice purposes. Content and standardization need to be regulated for the approval of the use of Apps in the mental health field for mitigating stress. In the pursuit of enhancement of positive mental health, scientific and evidence-based information is required to be curated for well-being apps. Mental Health and Normalcy Augmentation System Positive mental health App was developed based on robust scientific evidence in collaboration with National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro-Sciences, AFMC, and Centre for Development of Advanced Computing Bengaluru, under the Prime Minister Science and Technology Advisory Committee, Office of Principal Scientific Advisor to Government of India. The App focuses on the promotion of positive mental health.

Current Programs

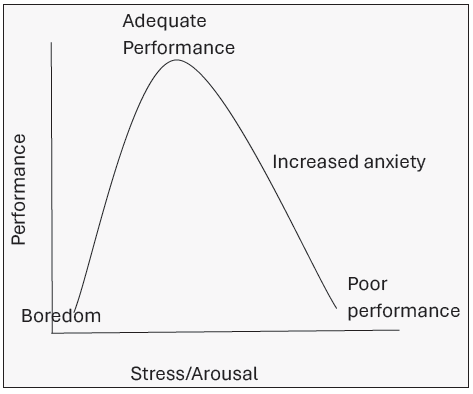

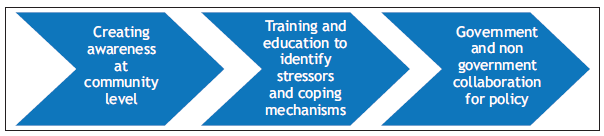

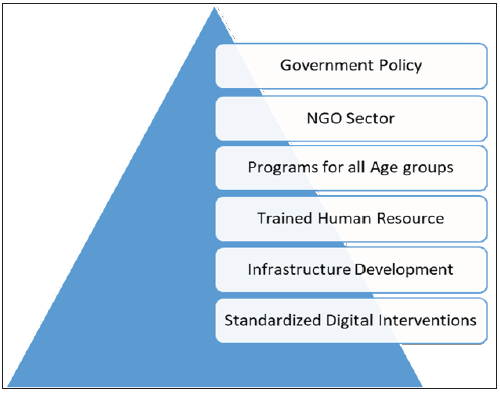

Over the years, Government of India have launched various mental health programs to promote mental health and prevent mental illnesses [Figure 3].

-

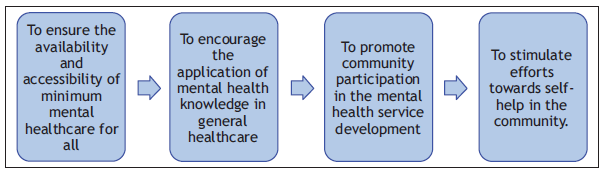

National Mental Health Program

The Government of India launched the NMHP in 1982, with the following objectives. As shown in Figure 4, NMHP has delineated various objectives to create an environment of awareness. It helped in promoting community participation in the mental health services and providing minimum healthcare available for all.

-

District Mental Health Program (DMHP)

The DMHP is a government scheme launched in 1996 to provide mental health services at the district level and integrate mental health services into primary healthcare.

The DMHP was initiated under NMHP in 1996 (during the IX 5-year plan). Modeled after the “Bellary Model,” DMHP encompasses the following components:

Early detection and treatment

Training: Providing short-term training to general physicians for the diagnosis and treatment of common mental illnesses and utilizing a limited range of drugs under specialist guidance. Health workers are also trained to identify individuals with mental illnesses.

IEC (Information, Education, and Communication): Creating public awareness

-

Monitoring: Primarily for straightforward record-keeping purposes

DMHP addressed workplace stress management, life skill training, counseling in schools and colleges, and community awareness prevention and promotion at the district-level healthcare delivery system.

-

Ayushman Bharat - Health and Wellness Centers (AB-HWC)

Ayushman Bharat – Health and Wellness Centers (AB-HWC) is a flagship program of the Indian government launched in 2018 intending to provide comprehensive primary healthcare services to all individuals. The program aims to establish 150,000 health and wellness centers across the country by 2022.

-

Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan:

The Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, launched in 2020, is a self-reliance program aimed at promoting economic growth and development in India. The program also focuses on addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of individuals. The schemes have focused on integrating mental health services into the general healthcare system and promoting community-based mental health care. This further was envisaged to help reduce stigma and improve mental health.

-

Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram:

Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) is a national program launched in 2014 to improve the health and well-being of adolescents in India, including their mental health.

- Initiatives by government of India.

- Objectives of National Mental Health Program (NMHP).

Mental health programs in schools in India

The “Mental Health Justice” program by the Mental Health Innovation Network was started to bring mental health services to school spaces. This program aimed to pilot a replicable mental health justice program in schools in Mumbai that included sensitizing stakeholders in schools about mental health issues and building their capacity to support the cause.

Yuva Mitra in Goa is a community-based program for youth health promotion, which includes peer-to-peer learning, teachers’ training, and awareness programs on youth health subjects like mental and reproductive health. On evaluating its impact, the program piloted in rural and urban areas showed more openness toward seeking help for mental health issues like substance and sexual abuse and suicidal thoughts.

SAATHI in Sikkim: “SAATHI” stands for Sikkim Against Addiction Toward Health India. It exerts that mental health issues (especially in a context like Sikkim, India) are intricately linked with substance abuse and thus uses a “peer education” model to advocate against drug use among school students, staff, and parents.

Budget allocation

The optimum level of training of mental health professionals will take decades to reach the ideal number of Mental healthcare professionals training in the country.

Out of the total ₹86,200 allocated last year, the budget for mental health was ₹791 crores, which was 0.92% of the total health budget. This year, it has marginally increased to 1.03% and as per Table 2, it amounts to 919 crores out of 89165 crores allotted for health. In this year’s budget, the line item of NMHP under tertiary activities has been used as the Tertiary Care Program. The tertiary components of the NMHP are mandated for strengthening Post Graduate Training Departments of mental health specialties, establishing Centers of Excellence and modernizing state-run mental health hospitals.

| Budget head | In crores |

|---|---|

| Total GOI budget for 2022–2023 | ₹ 45,03,097 |

| Total budget for health (MoHFW) | ₹ 89,155 |

| Total budget for social justice and empowerment (Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment [MoSJE]) | ₹ 14,072 |

| Direct expenditure for mental health (from MoHFW) | ₹ 919 |

| Indirect expenditure for mental health (from MoSJE) | ₹ 280 |

| Total budget for mental health | ₹ 1,199 |

https://cmhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Budget-Brief-2023-v3.pdf (Center for the Mental Health Law and Policy). GOI: Government of India, MoHFW: Ministry of health & family welfare

KEY ISSUES AND GAPS IDENTIFIED IN THE CURRENT SITUATION IN THE COUNTRY IN CONTEXT OF THE PROBLEM OR HEALTH ISSUES

Mental health awareness and stress management have been subjects of concern in India, as in many other countries around the world. While there have been significant advances and modifications, there are still numerous gaps in mental stress intervention. A mental healthcare deficit is defined as a large and persistent absence of necessary resources, amenities, and support for those living with mental health concerns or in mental stress. This weakness can present itself in a variety of ways with major ramifications for individuals as well as the community as a whole. In the context of the problem, there are key issues that require close consideration for impactful mental stress management. These issues are discussed below.

-

Stigma

The stigma attached to mental health concerns has been one of India’s greatest obstacles. Many people are reluctant to ask for assistance due to fear of being judged or misunderstood. It is vital to promote awareness about mental health and lessen stigma.

Stigma encompasses a negative or derogatory belief, perception, or stereotype associated with a specific characteristic, attribute, identity, or group of individuals. This often results in social exclusion, discrimination, and a sense of shame or disgrace for those possessing the stigmatized attribute. Public stigma consists of three main components: stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. These negative perceptions contribute to the fear of social distancing in individuals with mental illnesses. Similarly, self-stigma prompts an individual to socially distance themselves. Stigma serves as a hindrance to recovery; epidemiological research indicates that over half of the individuals who could benefit from mental health services do not access them.

The comprehensive survey, NMHS of India, 2015–16, found that nearly 80% of people with mental health disorders did not seek any form of treatment due to stigma and the fear of social discrimination. Venkatraman et al.99 (2019) assessed the stigma toward mental health issues among higher secondary school teachers in Puducherry, South India, which showed that around 70% had a stigma toward mental health symptoms. Stigma against mental illness is prevalent among not only the general population but also healthcare professionals in India. The stigma among professionals can affect the quality of care offered to individuals experiencing mental health issues. In a tertiary care center (medical college) in North India, nearly three-fourths of the 442 residents considered that they had significant mental stress; however, only about 13% sought help from mental health professionals. The two main barriers reported for not seeking help included the stigma of being labeled as mentally ill (54.6%) and being labeled as weak among their peers (58.1%). A systematic review revealed that less than one out of six medical students with depression sought psychiatric help and demarcated stigma as the most common factor. Further, many of these people adopted social stigma and experienced a loss of self-esteem and self-efficacy. They were also worried about repercussions and of being judged by their supervisors.100

Thus, the paucity of mental health literacy among the Indian population is aggravating stigma, myths, and misconceptions related to mental illness. Hence, stigma gets strengthened due to a lack of proper education methods and improper information dissemination. The stigma associated with mental health is a complex issue influenced by cultural, social, and economic factors, and efforts to combat it often involve public education, awareness campaigns, and destigmatization efforts by both the government and non-governmental organizations.

-

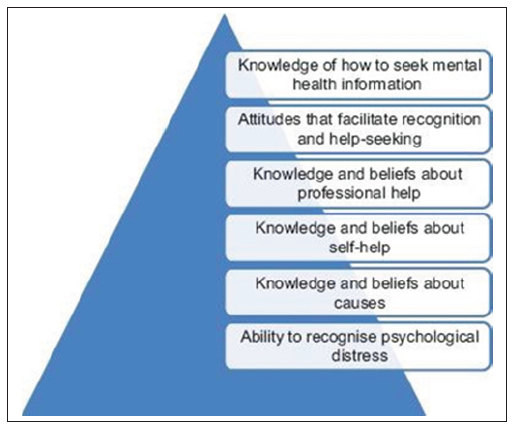

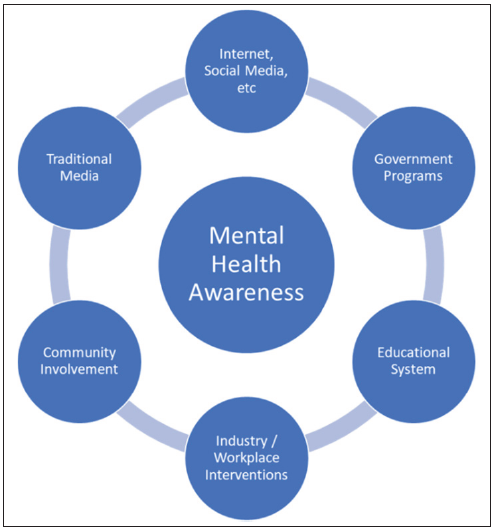

Lack of public education – “Mental health literacy”

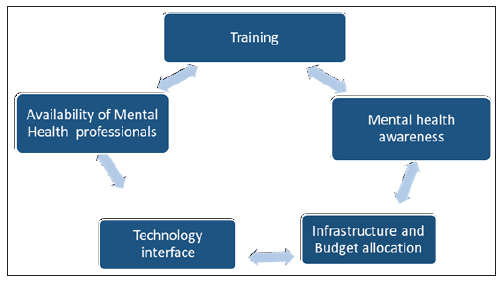

People are generally unaware of mental health concerns, including how to identify symptoms or seek help [Figure 5]. This lack of information leads to delayed action and the perpetuation of stigma. Most of us are aware of the necessary professional support available for the treatment of major physical ailments, as well as some of the medical or complementary therapies. This knowledge also underlies substantial support for community resources to deal with these bodily ailments. This is in contrast to mental health issues, where, largely, people are unaware that they are suffering and that help for substantial improvement is available. Similarly, community resources are not relatively aligned to deal with mental illness.

Figure 5:

Figure 5:- Attitude, and knowledge of mental health issues.

Mental health literacy is defined as “knowledge and beliefs about mental health issues that aid their recognition, management, or prevention.” So, it is limited not only to knowledge but also to an awareness of appropriate actions and behaviors to prevent and manage mental health issues. This term is useful as it targets community awareness, which has been neglected at the cost of the focus on mental health at primary care levels and the training of registered medical practitioners.

This frivolous mental health literacy was highlighted by Ogorchukwu et al.101 (2016), wherein his study showed that the percentage of mental health literacy among adolescents in south India was very low, at 29.04% for depressive symptoms and 1.31% for psychotic symptoms, both of which also have implications for mental stress. The study also showed that informal sources (including family members) were preferred sources for information over formal sources, highlighting widely ingrained stigmatizing attitudes regarding mental health conditions.