Translate this page into:

Time Trends in Prevalence of Anaemia in Adolescent Girls

Correspondence: Dr. Prema Ramachandran, Director, Nutrition Foundation of India, C-13, Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi 110016. Mob : 9891485605. Email: f1prema@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction:

Anaemia in adolescent girls has been recognised as a major public health problem. The Mid-day meal programme guidelines envisage inclusion of 75 g/day of vegetables and use of iron fortified iodised salt for hot cooked meal. The National Iron Plus Initiative envisages weekly iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation for adolescent girls; however, coverage and compliance have been reported to be low. Data from national surveys carried out in the last two decades were analysed to assess changes, if any, in Hb levels and prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls.

Material and Methods:

Raw data from National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) -2, -3, and -4, District Level Household Surveys (DLHS) 2 and 4, and Annual Health Survey-related to Clinical, Anthropometric and Biochemical Components (AHS-CAB) were analysed to assess mean Hb, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb in adolescent girls. Comparison in these parameters was made between non-pregnant girls 10-14 years and 15-19 years of age in DLHS-2, -4 and AHS-CAB; in the 15-19 year age group comparisons were made between pregnant and non-pregnant girls in NFHS series and DLHS AHS series.

Results:

There were no clear and consistent changes in mean Hb, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb in pregnant and non-pregnant adolescent girls between NFHS-2, -3 and -4 either at national or at State level. However, there was a 0.7 and 1.3 g/dL increase in mean Hb levels in non-pregnant girls (10-19 yrs) between DLHS-2 and AHS-CAB and DLHS-4 States, respectively. The increase in mean Hb of pregnant girls (15-19 yrs) was 1.1 g/dL and 1.4g/dL in AHS-CAB and DLHS 4 States, respectively. There was significant reduction in prevalence of anaemia in both pregnant and non-pregnant girls between DLHS 2 and DLHS 4 and AHS-CAB at the aggregate level for each survey and in all States except Uttarakhand.

Conclusion:

There has been some improvement in Hb levels in adolescent girls in the last two decades. Improving dietary intake of vegetables and promoting use of iron fortified iodised salt in all households in the country have to be taken up so that iron intake across all age groups improves. This when combined with daily IFA supplementation for three months in a year in adolescent girls, might lead to sustained improvement in Hb.

Keywords

Iron and Folic Acid supplementation

dietary intake of iron

dietary diversification

double fortified salt.

Introduction

India had recognized that anaemia in adolescent girls was a major public health problem with adverse consequences to the girl and, if she conceives, her child. Research studies in India had documented that infants born to anaemic mothers had poor iron stores. Prevalence of anaemia in children is high because of poor dietary intake of iron and folate, and poor bio-availability of iron from Indian dietaries. Efforts are being made to increase iron intake through inclusion of vegetables and iron fortified iodised salt in the hot cooked meal in mid-day meal programme. Increased requirement of haematopoietic nutrients during adolescent growth and onset of menstruation aggravate anaemia in adolescent girls. Early marriage and pregnancy not only perpetuate anaemia in adolescent girls but result in adverse health consequences for the mother-child dyad. In view of the high prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls (1-9), studies were taken up to assess the feasibility, acceptance, compliance, continuation rates and impact of daily, bi-weekly and weekly supplementation of iron (100 mg) and folic acid (500 µg) to adolescent girls (10-18). These research studies showed that school-based once-a-week supervised iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation was feasible; supplementation over one year resulted in improvement of iron stores and Hb by 0.5 g/dL. Based on the encouraging results from research studies, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India, initiated the supervised Weekly IFA Supplementation (WIFS) Programme to reduce the prevalence and severity of anaemia in adolescent school girls (19). The programme has been implemented across the country both in rural and urban areas. Data from large scale national surveys were analysed to assess changes, if any, in Hb status of adolescent girls in the last two decades.

Material and methods

In the last two decades Hb estimation in pregnant and non-pregnant women and adolescent girls had been undertaken by National Family Health Surveys (NFHS)-2 (1998-99) (1), -3 (2005-06) (2), and -4 (2015) (3), District Level Household Surveys (DLHS)- 2 (2002-04) (6), -4 (2013-14) (7) and Clinical and Anthropometric and Biochemical (CAB) Component of the Annual Health Survey (AHS 2014-15) (AHS-CAB) (8). Prevalence of anaemia was computed using the cut-off Hb of 12 g/dL in non-pregnant and 11 g/dL in pregnant girls.

NFHS undertook the survey in pregnant and non-pregnant girls between 15 and 19 years of age and used Haemacue method for estimation of Hb. Raw data from NFHS 2, 3 and 4 were obtained from Demographic and Health Survey Programme ICF International. Only those adolescent girls who had Hb levels between 2.5 to 18.0 g/dL were included for the analysis. Actual Hb values without any weightage and without any correction for altitude or smoking were used for analysis. Data from NFHS 2, 3 and 4 were analysed for mean Hb levels, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb at national and State level for both pregnant and non-pregnant adolescent girls.

Raw data of DLHS-2 and -4 were obtained from International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai; raw data of AHS-CAB was obtained from Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Govt of India. DLHS-2 covered all the States and UTs; AHS-CAB covered 9 poorly performing States (AHS-CAB States), while DLHS 4 covered 21 States and UTs (DLHS 4 States). DLHS 2, 4 and AHS-CAB surveyed the girls between 10 and 19 years. Hb estimation in DLHS 2, 4 and AHS-CAB was carried out using cyanmethaemoglobin method. Only those adolescent girls who had Hb levels between 2.5 and 18.0 g/dL were included for the analysis. Actual Hb values without any weightage were used for analysis. The mean Hb, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb in adolescent pregnant and non-pregnant girls in the 15-19 year age group were computed in DLHS 2 and 4 and AHS-CAB. The mean Hb, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb in non-pregnant girls in 10-14 year and 15-19 year and pregnant girls in 15-19 year age groups in DLHS 2 were compared with the prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb in the corresponding groups in DLHS-4 and AHS-CAB.

Results

The number of adolescent girls (pregnant and non-pregnant) surveyed, blood sample collected and valid Hb results available in different surveys are shown in Table 1.

| Age | Survey | Total No. surveyed | No. of blood samples collected | No. with valid Hb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-14 year (Non-pregnant) | DLHS 2 (AHS States) | 95245 | 57275 | 51070 |

| AHS States | 100794 | 64967 | 64960 | |

| DLHS 2 (DLHS 4 States) | 62386 | 36506 | 33200 | |

| DLHS 4 States | 51380 | 47610 | 43461 | |

| 15-19 year (Non-pregnant) | DLHS 2 (AHS States) | 72719 | 41948 | 37540 |

| AHS States | 102797 | 61463 | 61461 | |

| DLHS 2 (DLHS 4 States) | 56920 | 30913 | 28380 | |

| DLHS 4 States | 53030 | 50571 | 46459 | |

| NFHS 2 | 3089 | 2686 | 2682 | |

| NFHS 3 | 2326 | 2144 | 2144 | |

| NFHS 4 | 119655 | 116615 | 116564 | |

| 15-19 year (Pregnant) | DLHS 2 (AHS States) | 3850 | 2682 | 2295 |

| AHS States | 1332 | 1025 | 1024 | |

| DLHS 2 (DLHS 4 States) | 2145 | 1589 | 1452 | |

| DLHS 4 States | 1210 | 1172 | 1056 | |

| NFHS 2 | 444 | 392 | 392 | |

| NFHS 3 | 319 | 292 | 292 | |

| NFHS 4 | 3652 | 3573 | 3571 |

Mean Hb levels in pregnant girls were lower as compared to the non-pregnant girls in NFHS 2, 3 and 4. Mean Hb level in non-pregnant and pregnant girls were lower in NFHS 3 as compared to NFHS 2. Mean Hb in non-pregnant girls in NFHS 4 was higher as compared to the mean Hb level in NFHS 2 and 3. However, there were no differences in the mean Hb levels in pregnant adolescent girls between the three surveys (Fig. 1).

- Mean Hb in adolescent girls

The mean Hb in pregnant girls was lower than the mean Hb in the non-pregnant girls in all the surveys. The mean Hb in the AHS States both in non-pregnant and pregnant girls were lower as compared to the corresponding groups in DLHS 4 States. There was substantial improvement in the mean Hb both in non-pregnant and pregnant girls over time in both AHS and DLHS 4 States. The improvement in mean Hb level was lower in AHS States: 0.7 g/dL in non-pregnant and 1.1g/dL in the pregnant girls. In DLHS 4 States the improvement was 1.3 g/dL in non-pregnant and 1.4 g/dL in the pregnant women (Fig. 1).

Prevalence of anaemia in pregnant and non-pregnant girls in NFHS 2, 3 and 4 are given in Fig. 2 Prevalence of anaemia in pregnant and non-pregnant girls was similar in NFHS 4. Prevalence of anaemia was higher in both pregnant and non-pregnant girls in NFHS 3 as compared to NFHS 2; prevalence of anaemia in pregnant and non-pregnant girls was lower in NFHS 4 as compared to both NFHS 2 and 3 (Fig. 2).

- Prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls

Comparison of prevalence of anaemia in non-pregnant girls (10-14 and 15-19 years) and pregnant girls (15-19 years) in DLHS 2 with prevalence of anaemia in DLHS 4 and AHS-CAB in these groups showed that there was substantial reduction in prevalence of anaemia between DLHS 2 and AHS-CAB and DLHS 4 both in non-pregnant and pregnant girls. The difference in prevalence of anaemia in pregnant and non-pregnant girls in all the surveys was small except in AHS-CAB (Fig. 2).

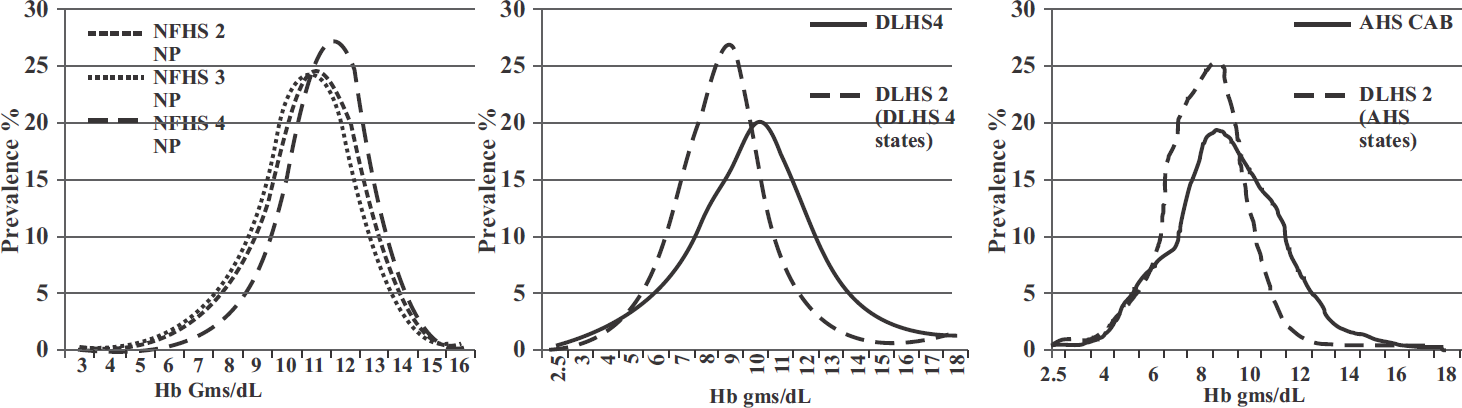

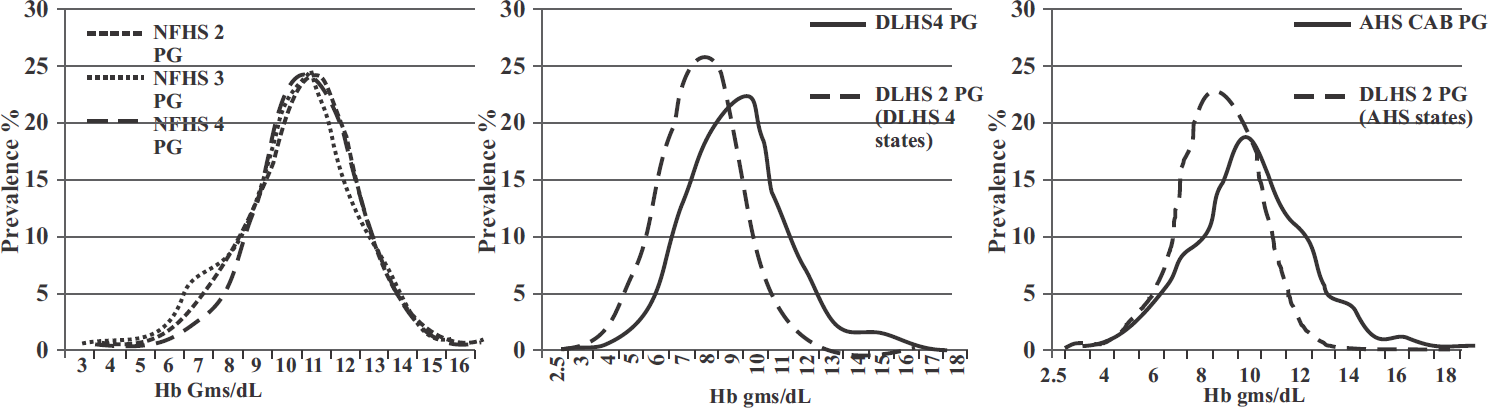

Frequency distribution of Hb in different surveys is shown in Fig. 3, 4 and 5. There was shift to the left in the frequency distribution of Hb in 15-19 year non-pregnant girls in NFHS 3 as compared to NFHS 2; in NFHS 4 the shift was to the right of both NFHS 2 and 3 (Fig. 3). Comparison of frequency distribution of Hb in non-pregnant girls (15-19 years) in DLHS 2 and AHS-CAB and DlHs 4 States showed that there was a clear shift to the right in Hb frequency distribution in the latter surveys (Fig. 3). While there was no shift in the frequency distribution of Hb in pregnant adolescent girls in NFHS, a clear shift to the right in frequency

- Frequency distribution of Hb in 15-19 yr non-pregnant girls

- Frequency distribution of Hb in 15-19 yr pregnant girls

- Frequency distribution of Hb in 10-14 yr girls

distribution of Hb was seen in pregnant adolescent girls in DLHS-2 and DLHS 4 and AHS- CAB (Fig. 4). The frequency distribution of Hb in non-pregnant girl in the age group 10-19 years in DLHS 4 and AHS-CAB showed clear shift to the right as compared to DLHS 2 (Fig. 5).

There were substantial inter-state differences in the prevalence of anaemia in non-pregnant adolescent girls in NFHS and in DLHS and AHS-CAB States. However, in NFHS series none of the States showed consistent or significant reduction in prevalence of anaemia in non-pregnant adolescent girls. Prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls was lower in DLHS 4 States as compared to AHS-CAB States at both the time points. In all States except Uttarakhand prevalence of anaemia was lower in AHS-CAB and DLHS 4 as compared to the prevalence in DLHS 2 in these States (Fig. 6).

- Inter-state difference in prevalence of anaemia in 10-19 yr non-pregnantt girls

Discussion

In India dietary intake of vegetables rich in iron and folate is low; bioavailability of iron is poor because of the high phytate and fibre contents of the diet. Therefore, right from the childhood, the prevalence of anaemia is high. Adolescent girls require additional iron and other nutrients to meet the needs for adolescent growth spurt and onset of menstruation. These requirements cannot be met from conventional habitual diets and, therefore, there is increase in prevalence and severity of anaemia in adolescent girls. Early marriage and advent of pregnancy in adolescent girls aggravates anaemia further and can result in adverse consequences to the mother-child dyad. IAF supplementation in adolescent girls might reduce the prevalence and severity of anaemia in them and may even help them in becoming non-anaemic before they become pregnant.

Research studies in India have shown that weekly IFA supplementation is feasible and brings about an improvement in mean Hb by 0.5 g/dL/year. With increasing proportion of girls attending the upper primary and secondary schools, they can be reached and provided WIFS supplements readily in schools; out-of-school adolescent girls could be contacted through Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme in anganwadis and given WIFS supplements. In view of this Govt of India has initiated the nationwide WIFS Programme in 2015. However, available meagre reports suggest that coverage under the programme was suboptimal in many States. The suboptimal coverage is partly due to side effects of iron and partly due to the problems in sustaining round-the-year supplementation year after year for a problem which is asymptomatic and where improvement is not perceptible to the person receiving the supplement. It is essential to find out whether there has been any improvement in Hb status of adolescent girls over the last two decades so that appropriate mid-course corrections can be done in the on-going interventions.

Data from NFHS, DLHS and AHS were analysed to assess changes, if any in mean Hb, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb in adolescent girls in the last two decades. Data from the NFHS surveys showed that between NFHS 2 and 3 that there was a small decline in mean Hb (Fig. 1) and 5% increase in prevalence of anaemia (Fig. 2); between NFHS 3 and 4 there was an improvement in mean Hb and 10% reduction in prevalence of anaemia (Fig. 1 and 2). The reason for the higher prevalence of anaemia in NFHS 3 is not clear. The data from the NFHS 2, 3 and 4 showed that improvement in Hb levels and reduction in prevalence anaemia in adolescent girls was small.

NFHS data are widely used by academics and programme managers to assess time trends in access to health and nutrition services and progress in terms of improvement in health and nutritional status. The data from NFHS showing lack of change in Hb status of adolescent girls over the last two decades was interpreted as being due to poor coverage and compliance with the WIFS programme for the adolescent girls. However, it is possible that the reported lack of improvement in Hb could, at least in part, be due to the problems in the method (Haemacue) used for Hb estimation in NFHS 2, 3, and 4. There have been publications indicating that Haemacue does not estimate Hb accurately (20-23).

To explore this possibility, comparison was made with data on mean Hb, prevalence of anaemia and frequency distribution of Hb from DLHS 2 and 4 and AHS-CAB surveys which were undertaken during the same period and used the gold standard cyanmethaemoglobin method for Hb estimation. Hb data from DLHS 4 and AHS-CAB showed that as compared to DLHS 2, there was an increase in mean Hb, reduction in prevalence of anaemia, and shift to the right in frequency distribution of Hb both in non-pregnant (10-14 years and 15-19 years of age) and pregnant (15-19 years) adolescent girls (Fig. 1-5) in both AHS-CAB and DLHS 4 (for their respective States). It was reassuring to note that there has been some improvement in Hb status of adolescent girls, despite the fact that the national level Weekly IFS supplementation (WIFS) programme was initiated only in 2015 and the reported coverage under the programme was low.

Over the last two decades, there has been substantial improvement in per capita income, reduction in poverty and improvement in household food security and a slow but steady decline in under-nutrition rates; access to healthcare for malaria and hook worm infestation has improved. It is possible that the observed improvement in mean Hb and reduction in prevalence of anaemia both in non-pregnant and pregnant adolescent girls might be part of the overall improvement in nutrition and health status of adolescent girls. It is, however, a matter of concern that prevalence of anaemia across all States of the country continues to be unacceptably high. There is an urgent need to accelerate the pace of improvement in Hb and reduction in prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls using all available interventions.

The WHO had consistently recommended oral iron supplementation as a public health intervention for improving Hb and iron status and reducing the prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls. Systematic reviews of the randomized clinical trials with IFS supplementation in adolescent girls (24) have shown that even in situations where prevalence of anaemia was high, IFS supplementation for three months or longer resulted in improvement in mean Hb (of about 0.5 to 1 g/dL). Improvement in Hb and ferritin levels was higher in daily supplementation as compared to biweekly or weekly supplementation, but compliance with daily supplementation was difficult to maintain on long term basis. Taking the operational difficulty in daily supervised administration of IFS tablets to adolescent girls, the earlier WHO guidelines had recommended weekly IFA supplementation (25). However, such intermittent supplementation has to be continued throughout the year, and year after year. Round-the-year supervised weekly IFA supplementation may pose problems in many settings. The current WHO guidelines recommend daily IFA supplementation for 3 months every year in settings where prevalence of anaemia is 40% or higher (26).

In the Indian context it may not be possible to rely solely on continued IFA supplementation to adolescent girls to achieve sustained reduction in prevalence of anaemia. Supplementation programmes are expensive because personnel are required for counselling, distributing supplements and monitoring to improve compliance. It has been well documented that not all anaemic persons become non-anaemic after three-months of daily supplementation; once supplementation is stopped some of those who became non-anaemic may become anaemic (27-30). Taking these into consideration, the WHO advocates food fortification with iron for sustained improvement in iron intake in countries with low iron intake (31). In India, low iron intake and poor bioavailability of iron from Indian diets are the major factors responsible for the high prevalence of anaemia across all age and physiological groups. The National Iron Plus Initiative guidelines recommend increasing vegetable intake and use of iron fortified iodised salt (double fortified DFS) at household level (32). Government of India's guidelines mandate use of DFS and vegetables in the mid-day meal programme for school children and hot cooked meal provided to the 3-5 years old children under ICDS; efforts are being made to fully operationalize these guidelines. Simultaneously, efforts to improve vegetable intake and promote use of DFS in all households in the country have to be taken-up so that iron intake across all age groups improves. This when combined with daily IFA supplementation for three months in a year in adolescent girls, might lead to sustained improvement in Hb. These efforts in reducing prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls will, in the long run, enable the country to move towards Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of 50% reduction in anaemia in women.

References

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 4 Fact sheets http://rchiips.org/ nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-4.shtml (accessed )

- Prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies. 2003. NNMB technical report. 22 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women and adolescent girls in 16 districts of India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2006;27(4):311-315.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of an appropriate strategy to control anaemia in adolescent girls of poor communities. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:261-267.

- [Google Scholar]

- Weekly iron and folic acid supplementation with counseling reduces anaemia in adolescent girls: a large-scale effectiveness study in Uttar Pradesh, India. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(3):186-194.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent girls' anaemia control programme, Gujarat, India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:584-589.

- [Google Scholar]

- Directly observed iron supplementation for control of iron deficiency anaemia. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61(1):37-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with high compliance/feasibility during iron and folic acid supplementation in a tribal area of Madhya Pradesh, India. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:377-380.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekly iron folate supplementation in adolescent girls-an effective nutritional measure for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(3):188-194.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A community-based cluster randomized controlled trial of “directly observed home-based daily iron therapy” in lowering prevalence of anaemia in rural women and adolescent girls. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27:NP1333-1344.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of weekly iron folic acid supplementation with and without vitamin B1 2 on anaemic adolescent girls: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(6):730-737.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness and Feasibility of Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation to Adolescent Girls and Boys through Peer Educators at Community Level in the Tribal Area of Gujarat. Indian J Community Med. 2016;41(2):158-161.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Mission GOI. Weekly iron folic acid supplementation (WIFS) 2015. (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study on prevalence of anaemia in women by cyanmethaemoglobin and Haemacue methods. Indian J Community Med. 2002;XXVII(2):58-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of Haemacue method with cyan methae moglobin method for estimation of hemoglobin. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:743-746.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of hemoglobin estimation using Haemacue. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:25-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of hemoglobin estimates from filter paper Cyanmethaemoglobin and Haemacue methods. Indian J Community Med. 2004;29(3):14-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intermittent iron supplementation for reducing anaemia and its associated impairments in menstruating women Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12. 2011 Art. No.: CD009218

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intermittent iron and folic acid supplementation in menstruating women 2011. 2018. (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Daily iron supplementation in adult women and adolescent girls 2016. 2018. (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of supplementation with ferrous sulfate or iron bis-glycinate chelate on ferritin concentration in Mexican schoolchildren: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. 2014;13:71-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekly micronutrient supplementation to build iron stores in female Indonesian adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:177-183.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Potential Impact of Iron Supplementation during Adolescence on Iron Status in Pregnancy. J Nutr. 2000;130:448S-451S.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iron Supplements: Scientific Issues Concerning Efficacy and Implications for Research and Programs. J Nutr. 2002;132:813S-819S.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]